Muhammad Ali was a champion before he was a pariah, a hero before he was an activist.

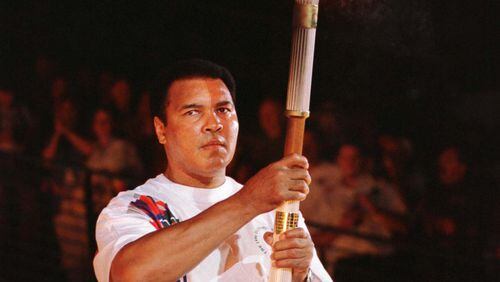

He was an icon before he was a patient, a global presence before he lit up the Atlanta sky.

He was The Greatest Of All Time.

Ali died Friday after a decades-long fight with Parkinson’s disease, the one opponent he couldn’t bluster or clobber. His legacy will live on, a testament to will, courage and determination.

“Muhammad Ali was The Greatest. Period,” President Barack Obama said Saturday. “If you just asked him, he’d tell you.”

But as global as Ali was, even in Atlanta — which in many ways is defined by race and its key role in the American Civil Rights movement — Ali play two small, but key roles.

It was in 1970, just as Atlanta was emerging as a nascent Southern city, that he staged his comeback to the ring after a three-year ban. And 26 years later, like Sherman, with a flaming torch in his hand, as Atlanta made its formal introduction on the global stage, he returned to light the Olympic caldron.

“He is part of the civil and human rights trajectory in this city,” Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed said of Ali.

In the arc of his life, when his legacy and global reach are considered, Ali’s meaning to people and his courage to go against the Vietnam War at the height of his physical prime – realizing, and disregarding the consequences – was without peer.

“I’m happy because I’m free,” Ali said once. “I’ve made the stand all black people are gonna have to make sooner or later, whether or not they stand up to the master.”

Kentucky to Italy, but not to Vietnam

He went from a poor kid growing up in a racist and segregated Louisville to an Olympic champion and darling of Rome in 1960. Four years later, he would become heavyweight champion for the first time, beloved and despised for his brashness, his rejection of Christianity in favor of Islam, and his refusal to pick up arms and fight in Vietnam.

But he was reborn at least twice – both times in Atlanta – to become one of the most recognizable and respected figures on the planet. He was Nelson Mandela before Mandela. Jordan and Tiger before Jordan and Tiger.

“Before there was a figure like President Barack Obama, beyond my own father, he was an extraordinary athlete with a terrific mental capacity who was absolutely fearless,” said Reed, who grew up in the 1970s and 1980s and added that he was overwhelmed by the power of Ali’s example and influence on his generation of black men. “To be a young boy and to see that example had a profound influence on my life.”

Ambassador Andrew Young, a former mayor of Atlanta, met Ali in the 1960s. At the time, Young was a key leader in the American civil rights movement working with Martin Luther King Jr. in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

Ali was the heavyweight champion of the world, a Muslim and a member of the Nation of Islam, a then-fringe civil rights and religious group that was often at odds with mainstream groups like the SCLC.

But in 1967, a year before his death and as he became an increasing critic of the Vietnam War, King chose the words of the young, defiant prize fighter to help explain his position.

“Like Muhammad Ali puts it,” King said. “We are all – black and brown and poor – victims of the same system of oppression.”

In a later sermon, King continued his praise of Ali.

“Every young man in this country who finds this war objectionable and abominable and unjust will file as a conscientious objector,” King said. “And no matter what you think of Mr. Muhammad Ali’s religion, you certainly have to admire his courage.”

Cassius Clay becomes Muhammad Ali

Aside from boxing, it was Ali’s religion that defined him for many. In 1964, with the support of Malcolm X, a then-Cassius Clay converted to Islam, and became known as Muhammad Ali.

When he refused induction into the U.S. Army in 1967, Ali cited his religious faith as part of his objection. He also pointed out the hypocrisy of sending poor black men to fight wars abroad when their rights at home were challenged.

“Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?” Ali said.

Ali was hammered for his stance, was convicted of draft evasion and sentenced to five years in prison, a sentence ultimately thrown out by the U.S. Supreme Court. Yet, the opinions of even some of Ali’s former critics have eased in the decades since he was ostracized by much of white America. His service, and his grace, have smoothed many jagged memories.

Reid Derr, a history teacher at East Georgia State College attending the Georgia Republican Party convention, said Ali “was always sort of a big mouth, and I sorta reacted against him, but I admired him as a man and his struggle with Parkinson’s was admirable.”

Paul Peterson, a retired farmer from Evans County, was also at the GOP convention. Ali, Peterson said, had money on his side.

“I didn’t agree with that (dodging the draft) at all,” Peterson said. “I think that was just because he had so much money that he could afford to do whatever he wanted to do. You know, money talks.”

Still, Peterson said, Ali “was an American icon. He did good.”

‘Atlanta is so full of history of Muhammad Ali’

For Hank Aaron, who in 1967 was still seven years away from breaking Babe Ruth’s home run record, Ali’s standing up for his rights as a black man was a remarkable gesture.

“That is not an easy decision to make,” said Aaron, who was Major League Baseball’s final link to the Negro Leagues as the last player to play in both leagues. “But he believed in what he was doing, and didn’t believe in the war. I can’t think of a tougher decision, to throw away everything right in the middle of your prime as an athlete. You had to admire him for that. I really had a lot of respect for him.”

Young said that while traditional civil rights leaders and workers were in the trenches, Ali — whom he considers a civil rights icon — was setting a perfect example of black manhood and respect.

“You didn’t discuss with Muhammad. You listened to what he had to say and told him what you had to say,” Young said. “But he stuck by what he believed in, and people eventually came to believe he was right. I don’t know many people today who would defend the war in Vietnam. Ultimately, he was right.”

But for his defiance, Ali was stripped of his title and was barred from boxing throughout the United States. That was until 1970, when Georgia state Sen. Leroy Johnson was able to secure a license for Ali to fight Jerry Quarry in Atlanta.

Tom Houck served as King’s driver for years and now gives tours of famous Atlanta civil rights sites. The old Atlanta city auditorium, where Ali fought Quarry, is one stop. But it’s just one of many ways Ali made the city part of his legend, Houck said.

“Atlanta is so full of history of Muhammad Ali,” he said.

Houck was working for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference when Ali changed his name and became an outspoken proponent of civil rights and a critic of the war in Vietnam.

“When he did what he did, it was absolutely incredible,” Houck said. “In our movement, it was a gift. Because Muhammad Ali was doing something that not very people of his stature would do.”

Black, proud and beautiful

Michael Thurmond’s memories of Ali go back to at least 1974, when Ali fought George Foreman in Africa. Thurmond and his friends at Paine College in Augusta gathered around the radio to listen. Ali, he said, was a defining force for young black men.

“Look, James Brown was responsible for us being black and proud, but it was Muhammad Ali who made us black and beautiful,” Thurmond said. “Those two men, what a profound impact they had on African-American culture.”

Thurmond met Ali once, in the early 1990s, when the former boxer was honored in the Georgia General Assembly.

“It was amazing,” said Thurmond, a current candidate to be DeKalb County’s chief executive. “Considering his history, early on as a draft dodger and one of the most disliked black men in America, for him to be able to come to the Georgia House of Representatives to get a standing ovation and be celebrated by black and white members of the General Assembly was evidence that America’s opinion of him was transformed from a person of disrespect and dislike to one of the most celebrated, not just athletes, but men, on the planet.”

It wasn’t just young African-Americans that Ali influenced. Ray Harris of Carrollton, who is white, grew up in the South where he was taught that blacks were inferior to whites. Ali proved as a boxer that he was certainly not physically inferior, but it was his later stands that Harris said truly proved his value to the world.

“Had Muhammad Ali been one of those 58,000-plus names on the Vietnam Memorial, the world would have lost a fine athlete and a fine man,” Harris said. “He was also a role model for all young men, not just those with dark skin. And he was sure as hell not inferior in any way.”

LaNelle Holland, of Whitesburg, had a similar experience, similar upbringing. She first saw Ali, then Clay, on television in 1960 when he won the 1960 Olympic gold medal. Holland was questioning her Georgia upbringing, where society had tried to teach her that whites were the superior race.

Later, Holland watched the hypocrisy as those same people used Ali’s stance against the draft to claim superiority.

“Prominent young white men were getting deferred for all kinds of reasons while poor white men and black men from any walk of life were called to serve,” she said. “Throughout the news coverage of his conviction and sentencing I felt so bad. I truly admired Muhammad Ali and wanted to see what battles he would win next.”

‘He was the center of attraction’

Pambu Mwanda, an account manager for Habitat for Humanity, grew up in Zaire, the site of 1974′s “Rumble in the Jungle.” He was 8-years-old when the country watched Ali destroy George Foreman.

“Zaire was an emerging country and having Ali fight there was a crown jewel,” Mwanda said. “They showed that fight over and over every day for the next six months. He has had a long-lasting impact on a lot of Africans because he embraced Africa.”

It is no doubt that in his prime, as he was challenging Babe Ruth, Aaron was one of the most recognizable and famous people in the world. But even he admits that his fame was hing compared to Ali’s.

“He was the center of attraction. I carried my ID one hand. He had a fist full of IDs,” Aaron said “He was the reigning champion of the world and I respected that. I went to him, he didn’t come to me.”

A haircut, a torch and the world

Sitting in his South Atlanta home, Young smiled when talking about Ali. He said that that moreso than they grand gestures, Ali would always be defined by his little touches of kindness and humanity.

Since his death, for example, social media has been flooded with personal stories about ever so brief encounters and photographs. Usually of Ali, biting his bottom lip and holding a fist up to the smiling face of a child.

Young said a perfect example of Ali’s humanity came in 1996, when the former fighter was set to light the Olympic torch.The event was shrouded in secrecy, but it would immediately return Ali to the forefront of the global spotlight.

“He called me and said he wanted to get a haircut,” Young said.

Young told him that he would hire a barber and bring him to his hotel suite, but Ali refused. He wanted to go out. Young took him to Mitchell Brothers Barbershop at MLK and Holmes. Then they went to Raheem’s Fish Supreme — a local hole in the wall — to get something to eat.

“He took pictures with everybody in there, because he really enjoyed being around people,” Young said. “Then he got ready to light the torch.”

-- Erica Hernandez and Eric Stirgus contributed to this article.

About the Author