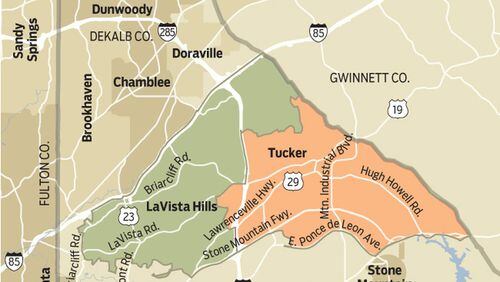

About the proposed cities

LaVista Hills

Population: 67,446

Services: Police, code enforcement, roads, drainage, planning, zoning, permitting, licensing, parks, recreation.

Government: Mayor and six city council districts.

Property taxes: Capped at 5 mills unless voters approve a higher rate.

Tucker

Population: 33,301

Services: Planning, zoning, code enforcement, licensing, parks, recreation.

Government: Mayor and three districts with two city council members from each district.

Property taxes: Capped at 1 mill unless voters approve a higher rate.

Voter support for previous cities

Sandy Springs (2005) … 94%

Milton (2006) … 86%

Johns Creek (2006) … 84%

Chattahoochee Hills (2007) … 84%

Dunwoody (2008) … 81%

Peachtree Corners (2011) … 57%

Brookhaven (2012) … 55%

Note: About 85 percent of voters rejected the proposed city of South Fulton in 2007.

Source: County Election Offices.

For the better part of a year, the campaigns have been waged at community meetings, with yard signs and through mass emails.

Tuesday, the battles for public opinion will come to an end when voters decide whether to carve the suburban cities of LaVista Hill and Tucker out of unincorporated DeKalb County.

If approved, the proposed municipalities would continue a trend toward cityhood that began when Sandy Springs formed in 2005. And, as the eighth and ninth new cities in the region, they would gain a degree of separation from a county government mired in allegations of corruption.

Born of a desire for greater self determination, these cities would give more than 100,000 DeKalb County residents local control of parks, planning, business licensing and more. But, in one swoop, they'd also change the face of the county, leaving behind unincorporated South DeKalb areas that have lower income and higher crime levels.

Supporters of LaVista Hills and Tucker say they want representatives who live in their neighborhoods, understand their communities and are responsive to their concerns. They say their areas have grown to the point where they need more attention than DeKalb’s government, which covers 722,000 people, can provide.

"DeKalb County isn't adequately meeting the needs of all its citizenry," said Ben Shackleford, a resident and member of the Briarcliff North Civic Association who backs LaVista Hills. "There's going to be a better opportunity for representation. And, if they spend some unreasonable amount of money, they'll have to answer to their neighbors."

Opponents of the cityhood movement say residents will bear the cost of hiring a fresh crop of bureaucrats and politicians without necessarily seeing better results.

“When governments are spending more money, it’s coming from taxpayers,” said Marjorie Snook, the president of DeKalb Strong, a group against the creation of new cities. “You don’t solve political problems by adding more politicians. What adding new politicians to this area does is increase the chances for cronyism and corruption.”

Each successful cityhood effort over the last decade has passed by slimmer margins. No public polls have been conducted, but there's been an intense campaign for and against cityhood.

LaVista Hills would take in more than 67,000 people in an area stretching from outside Emory University to the eastern edge of Interstate 285. Tucker would include about 33,000 residents, extending eastward from the Perimeter, with some land inside the highway.

Only those within the borders of the proposed cities can participate in the referendums. Residents living in other parts of unincorporated DeKalb don’t get a vote.

LaVista Hills would offer a full-service government, with police, road, zoning, permitting and park services. Tucker would start with a much smaller government controlling planning and zoning, code enforcement and parks.

Both cities would continue to rely on DeKalb for most of their local government, including water, sewer, court, sheriff, library and many other services. Tucker also would keep DeKalb police officers and pay for them through county property taxes instead of starting its own department.

Whether or not city residents would pay higher taxes and fees has been fiercely debated. The truth won't be known until future city councils in LaVista Hills and Tucker set local tax rates.

Kevin Levitas, a leader of the LaVista Hills effort and a former state representative, said the city would be run more efficiently than the county. Like the cities of Dunwoody and Brookhaven, founded in 2008 and 2012, he said LaVista Hills would result in lower property taxes.

“The status quo is a bloated county government akin to the federal government that’s become too large, too unwieldy, not in touch with the people and mismanages taxpayer dollars,” Levitas said. “When you look at the experience of Brookhaven and Dunwoody, the reality is they’re operating cheaper and doing a better job for taxpayers.”

But Gunter Sharp, a Georgia Tech emeritus professor who lives in the LaVista Hills area, said he’s skeptical of the no-new-taxes claim. His math indicates that residents would play slightly higher property taxes.

“They’ve been stonewalling and denying all the analysis,” said Sharp, a semi-retired teacher in the university’s school of industrial and systems engineering. “They’re falling back on the argument that Dunwoody and Brookhaven have lower millage rates and, therefore, LaVista Hills can do it. But the numbers are what they are.”

Tucker’s government would rely on licensing fees, franchise fees and insurance fees, with property tax rates similar to those residents currently pay, according to a Georgia State University feasibility study.

Tucker’s supporters say that cityhood is the next step for an area that’s already existed as a distinct community for more than 120 years. Tucker is so well known that many people think it’s already a city, said Michelle Penkava, a leader of Tucker 2015.

“We want people who live in Tucker making decisions for Tucker,” Penkava said. “Cityhood will enhance what makes Tucker a special place and ensure its success with local control over services directly related to economic development and quality of life.”

One resident who moved to the area about a year ago, Mario Chandler, signed up as a volunteer for the cityhood campaign because, as a city, Tucker will have more control over its future, he said.

“You can shape the city as you’d like it,” said Chandler, who teaches Spanish at Oglethorpe University. “DeKalb is this huge county, and Tucker isn’t able to get the same kind of personalized attention.”

If the cityhood referendums pass, roughly 300,000 people would live in DeKalb's 13 cities, and more than 400,000 people would remain in unincorporated areas that rely on the county government. DeKalb's government has estimated that it will lose about $13 million a year after accounting for a projected decline in tax revenue and service expenses.

About the Author