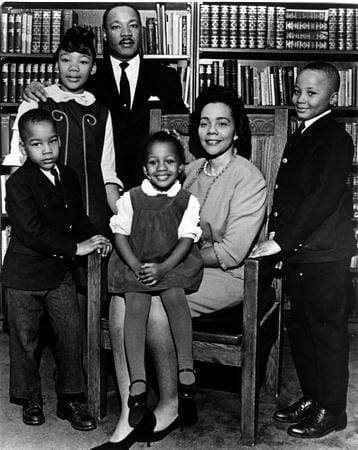

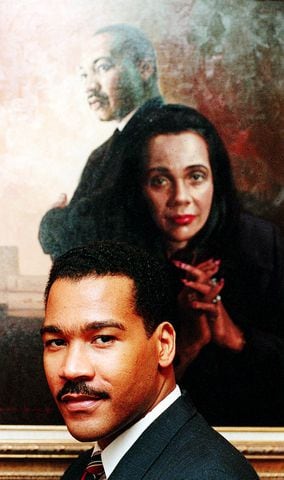

Each of the four children of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. carried, and still carry, a special piece of him with them.

For Yolanda King, she was the firstborn, the eldest.

Firstborn son, Martin Luther King III, carries the heaviness of the name.

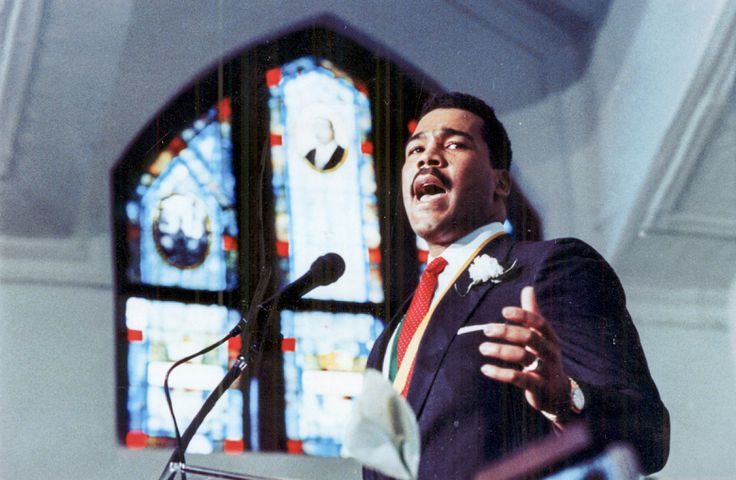

The youngest, Bernice King, is most like him in the pulpit, offering a mix of studied theology and fiery rhetoric.

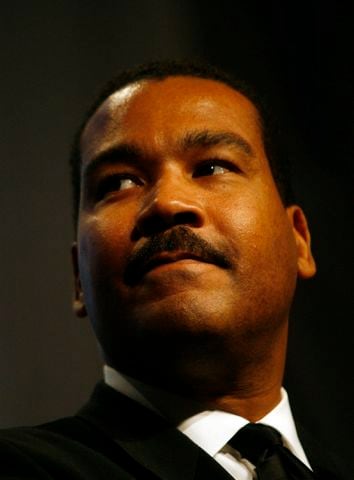

But it was Dexter Scott King, the youngest son, who looked just like his father and who, as the caretaker of his family’s intellectual legacy, might have carried the heaviest burden.

Dexter King was only 7 years old when he held his brother’s hand and marched with his family behind his father’s casket through the streets of Atlanta.

As an adult, Dexter Scott King assumed control of the King Estate, in charge of shaping his father’s legacy, as well as protecting the King family’s intellectual properties. It earned him some criticism.

Dexter’s business style, evident by the mountain of lawsuits and public disputes, often put him at odds even with his siblings to the point that he moved to California. He was rarely, if ever, seen in Atlanta over the last decade.

Dexter Scott King, the youngest son of Coretta and Martin Luther King Jr., died Monday after what the family said was a “valiant battle with prostate cancer.”

“He transitioned peacefully in his sleep at home with me in Malibu,” said his wife of 11 years, Leah Weber King. “He gave it everything and battled this terrible disease until the end. As with all the challenges in his life, he faced this hurdle with bravery and might.”

He was 62.

Aside from running the family’s business affairs, Dexter King’s life and career also became part of his family’s legacy. In 2002, because of the strong resemblance, he played his father in the 2002 film, “The Rosa Parks Story.”

A year later, he published his memoir, “Growing Up King: An Intimate Memoir.”

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

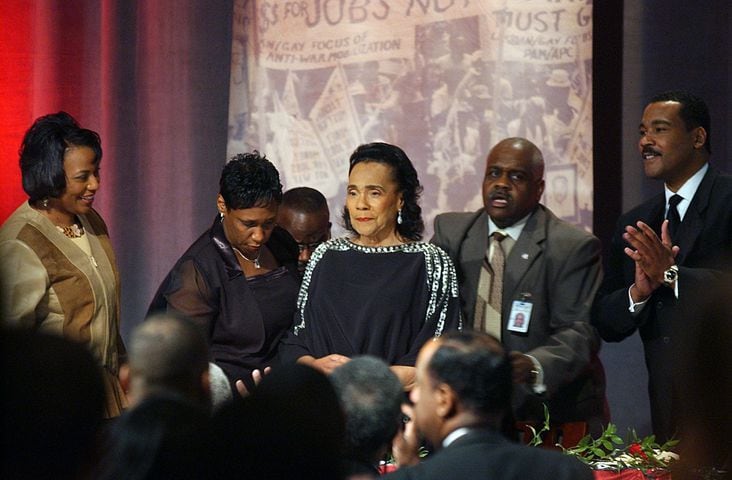

Bernice King, the youngest of the King children, said “Words cannot express the heartbreak,” of losing a sibling.

She runs the nonprofit King Center in Atlanta.

“I’m praying for strength to get through this very difficult time,” she said.

Yolanda King was the first child to die, suffering a heart attack in 2007, just a year after their mother, Coretta Scott King died of ovarian cancer and died on Dexter King’s 45th birthday.

“The sudden shock is devastating,” Martin Luther King III said Monday. “It is hard to have the right words at a moment like this. We ask for your prayers at this time for the entire King family.”

Throughout the city, tributes poured in for King, including messages from the Georgia Congressional Black Caucus, as well as the Atlanta City Council.

“His profound and unwavering love for his family positioned him as a guardian of his father and mother’s legacies,” said Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens. “Dexter held various titles — Morehouse Man, humanitarian, civil rights activist, and even actor. However, above all, he was a devoted family man.”

Dexter Scott King was born on Jan. 30, 1961. His parents named him after the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, where Martin Luther King Jr. served his first pastorate and where he led the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Like his father, Dexter King grew up in Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, where his grandfather, Martin Luther “Daddy” King Sr., served as pastor. King Jr. was co-pastor in the 1960s.

He played football at Atlanta’s Frederick Douglass High School, before following in his father’s footsteps, going to Morehouse College.

“We’re all incredibly proud,” said Matthew Jackson, a Morehouse senior from Detroit. “We learn about [the King family] in classes and see their quotes on everything. Seeing how much Morehouse cares about them and how they teach us to care shows me the importance of who they are and what they’ve done for us.”

In 2000, Dexter King moved to California to, among other things, pursue acting. But in 2016, he moved into a $1.8 million Buckhead mansion with his wife Leah Weber King, who he quietly married in 2013. The move back to Atlanta came in the middle of a contentious court battle which he was waging against Bernice King.

At issue was Dexter King and Martin Luther King III’s contention that a 1995 agreement gave the Estate of Martin Luther King Jr. Inc. ownership of all of their father’s property — specifically the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize and a Bible their father traveled with that was later used by President Barack Obama during his second inauguration.

In 2014, the brothers outvoted Bernice King 2-1 in favor of selling the items. Bernice King protested the move, arguing that the items were sacred. She had the items, and the family ended up in court.

“This is not an issue of wanting to sell them,” Dexter King said at the time. “This is an issue of ownership and retrieving property. An individual has sequestered property that belongs to the (King estate) corporation. We just want it back in its proper place. We want it properly protected, properly preserved and ultimately, at some point, developing a plan that deals with accessibility.”

That lawsuit, where former President Jimmy Carter — who negotiated peace between Israel and Egypt and has a Nobel Prize of his own — was brought in to mediate, was at least the fifth court proceeding that pitted the King siblings against each other over the previous decade.

Throughout the process, Dexter King often stressed that it was not he, the man, in court. Rather, he said, it was the King Estate, for which he served as president and CEO.

“I don’t take it to heart. No one agrees 100 percent on anything. That is the beauty of diversity,” he told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2015. “The reality is the King family should not be penalized because it has the need to seek redress in other forums.”

In 2016, a Superior Court judge signed a consent order clearing a path for the King Estate to sell the items. There is no indication that they were ever sold.

He was also litigious in going after corporations, media or others using his father’s quotations or images.

Andrew Young, 91, who worked in the civil rights movement with King and battled prostate cancer himself in his 60s, said he didn’t talk to Dexter King much in his later years, but understood what he was going through.

Dexter acted to protect his father’s legacy from many whom he felt were using it for their own benefit.

“Dexter resented people trying to take advantage of his father’s legacy, because he felt that people tried to use his father for their benefit, while he was alive,” Young said. “Dexter decided to copyright King’s words and to keep control over his intellectual legacy and that was seen as a negative by people.”

“He got a bad rap,” said Young, who was also the former mayor of Atlanta. “He was a good kid.”

The King family will meet with the media Tuesday morning to discuss plans for a memorial service for Dexter King.

Auzzy Byrdsell contributed to this story

Learn more

About the Author