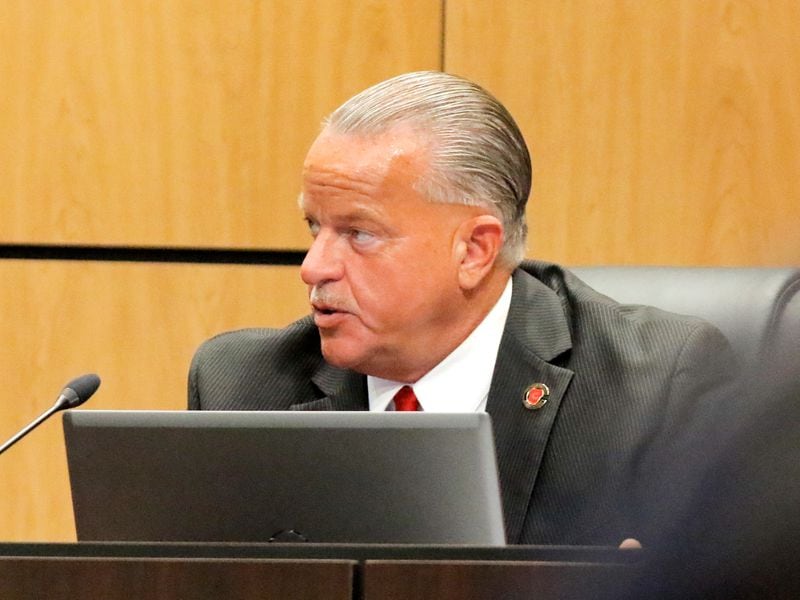

Addressing his recent decision to remove four popular teen novels, Cobb Schools Superintendent Chris Ragsdale said he didn’t consider his critics to be “evil.”

No, he explained at a recent board meeting, critics were “shortsighted, wrong and often motivated by reasons that reflect their social and political agendas that have absolutely nothing to do with the education nor protection of children.”

If Cobb hasn’t banned mirrors, Ragsdale should try looking at one.

His regime has exploited all the boogeymen of the political right, from masks to diversity-equity-inclusion to critical race theory to book bans. In October, the district sent a message to all families from its attorneys that lamented the “leftist activists” in a lawsuit by voting rights organizations that alleged school board maps intentionally discriminated against communities of color.

Amid all these political machinations, Ragsdale insists the goal is to promote and protect students of Cobb County.

Yet, when one of those students wrote a guest column for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution education blog in the fall challenging book bans, Cobb’s Office of Strategy & Accountability — at times more akin to an Office of Propaganda & Obfuscation — had no interest in promoting or protecting her.

Apparently tipped off that the 16-year-old might try to speak at a board meeting in September about book bans, Julian Coca, the Cobb school district’s director of content and marketing, sent a message to the communications staff that warned: “The student who wrote the article in the AJC is planning on speaking in public comment tomorrow. If so, has to have their parent with them (under the age of 18). If not — they can’t speak ... and the student’s mom is a member of the Board of Electors ... so .... she probably doesn’t want to be in the limelight on this particular issue.”

A spate of messages from staffers made public raises questions about whether their role is community relations and public engagement, as stated in the job descriptions, or whether they’re political operatives determined to shield the superintendent and silence any critics.

In a series of troubling exchanges in September about a planned rally by parents unhappy with the superintendent, Coca wrote, “There is a Replace Ragsdale rally planned for Thursday. Would be great to have a counter voice.”

In a message to Coca and press relations coordinator Nan Kiel, digital content specialist Eric Rauch reported, “They’re still making their signs for their little rally.”

When students being recognized at a meeting failed to show the deference to the superintendent that Rauch felt was required, he wrote, “All the Replace Ragsdale children turned their back during his recognition. They show their true natures.”

All school superintendents draw fire; if Mister Rogers helmed a school district, he and his cable-knit cardigans would have faced criticism. At the end of every interview, the superintendent in a high-pressure New Jersey district would tell me only half-jokingly, “If I’m run out of town tonight, it’s been nice working with you.”

So Cobb is not unique in the fractious relationship that Ragsdale has with some parents. What distinguishes Cobb is the bunker mentality that has developed and efforts to taint parents, teachers, media and even students who dare to raise legitimate questions about district decisions and policies.

For example, Ragsdale devoted a lot of his commentary at the recent school board meeting to denying that the removal of books from school shelves constituted a “ban” since children can still read the books at home. He linked the removing of the books — including the acclaimed coming-of-age novel “The Perks of Being a Wallflower” — to sex trafficking and the sexualization of children.

Protecting children from sexually inappropriate material, he said, “is a battle between good and evil. You are either in favor of forcing public schools to provide lewd, vulgar and sexually explicit materials to children or you are against it.”

Credit: Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Credit: Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Such explosive rhetoric mischaracterizes young adult books like “Perks of Being a Wallflower,” which mention sex and childhood sexual abuse but also speak to the experiences of many American teens around relationships, sexuality and growing up.

I read “Perks” as a parent after one of my kids recommended it. My review — too much teen angst for me — is irrelevant. What should matter is whether young readers relate to the book and benefit from it.

I spent an afternoon reading online reviews from teens, many of whom deemed the book life-changing and affirming. One young reviewer wrote: “Reading it as a teenager, before I had been diagnosed with autism, I found Charlie so understandable and comforting as a character. He felt like the friend I never had, but had always needed.”

The release of the internal messages among Cobb Schools communication staffers has increased concerns that Ragsdale and company are driven by a political agenda rather than an educational one. The messages were released after an open records request by former Cobb school counselor Jennifer Susko, who resigned in 2021 over limits placed on discussions of race and racism in the classroom. Susko shared the staff messages with the media.

The most alarming comments are those about students, especially about the high school student whose essay about the dangers of book bans was published in the AJC.

The high school junior wrote an excellent column that sparked a lot of discussion. A school leader and district communications team with the best interest of students at heart would have acknowledged her achievement rather than worry if she’ll criticize the boss or the district at a school board meeting. (Their efforts to gag potential critics included an unannounced change in the sign-up location for the limited slots to address the school board, frustrating people who had waited hours to sign up and leading to shoving matches.)

I agree with Ragsdale that Cobb students need protection, but it’s not from books. It’s from his staff.