On Nov. 2, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution will debut its first feature-length film, “The South Got Something To Say.”

The documentary tells the story of Atlanta’s rise as a hip-hop power, at the same time when the city was growing as a political, cultural and business Mecca — especially for Black folks.

Four people were chosen to tell this story.

Credit: Natrice Miller

Credit: Natrice Miller

All share a deep and passionate love of hip-hop and an equal amount of love for their adopted Atlanta homes.

Emmy-winners and co-directors Tyson Horne and Ryon Horne each grew up in Paterson, N.J. and Miami, respectively, where they brought a sense of the boom-bap with the booty-shaking.

Credit: Natrice Miller

Credit: Natrice Miller

Producer and writer Ernie Suggs was born in Brooklyn and was there when hip-hop started in the Bronx in 1973. But he came of age in rap’s Golden Era of the 1980s, in the suburbs of North Carolina where he went to high school and college.

And DeAsia Paige, a writer and producer on the project, who is so young, but so steeped in the modern aesthetic of hip-hop.

In advance of the movie’s premiere, we asked them to pen what hip-hop has meant to them. How hip-hop, inspired, motivated and sometimes hurt them.

These “love letters” also serve as a reminder of how much hip-hop has grown and how far it has to go to become a culture that’s truly inclusive.

DeAsia Paige: When hip-hop is complicated and intense

When did I fall in love with hip-hop?

Well, my answer to that question is as complicated as it is intense.

Credit: DeAsia Paige

Credit: DeAsia Paige

Because I’m not sure if I’ve ever truly loved it. Like being head-over-heels in love with it. Like the type of love Erykah Badu and Common rhymed about in “Love of My Life (An Ode to Hip Hop).”

To fall in love with something indicates that you trust it enough to know that it will catch you when you fall. As a Black woman, I’ve seen hip-hop abandon the landing too many times.

In the Boogie Down Productions’ 1987 classic, “The Bridge Is Over,” Bronx rap legend KRS-One dissed Roxanne Shanté by saying that she was “only good for” sexual relations.

She was only 16 at the time.

He was 21.

On “Fear of Heights,” a track from Drake’s 2023 album “For All the Dogs,” he seemingly disses his ex, Rihanna — a woman he hasn’t dated in nearly seven years — by claiming that she was only “average” in bed with him.

I can go on and on with more examples.

But there are artists who’ve made me fall in love with hip-hop more than I’ve fallen out of it.

Credit: DeAsia Sutgrey

Credit: DeAsia Sutgrey

When I hear songs like Lil Kim’s “Queen (expletive),” I’m reminded of the love that hip-hop can bring to me.

When I hear Missy Elliott’s “The Rain,” I’m reminded of hip-hop’s boundless creativity.

When I hear Kendrick Lamar’s “DNA,” I’m reminded of hip-hop’s unyielding defiance.

Chief Keef unlocks my own defiance. Tupac makes me feel like I’m not alone when it’s “me against the world.” Future, Babyface Ray, Veeze and Pooh Shiesty embrace my rage.

Megan Thee Stallion makes the confidence I want feel more tangible. Noname makes me feel seen.

Sometimes, I wish I could love hip-hop more.

Sometimes, I wish it could always love me back.

My love for hip-hop is often complicated and intense.

But it has provided me with a collection of valuable stories to last a lifetime.

Ryon Horne: You are a message

You taught me storytelling at 8 years old.

I watched a rapper, wearing a Kangol hat, a tracksuit and a gold chain, save his kidnapped girlfriend, who was abducted while passing out drug prevention flyers.

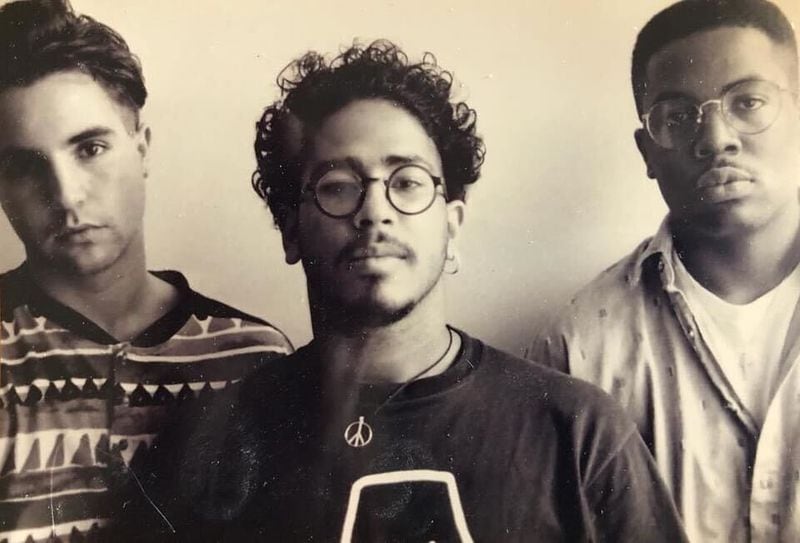

Credit: Ryon Horne

Credit: Ryon Horne

At 11, you taught me that ladies come first through a Queen, who sang the words and then spit fire.

This lesson stays with me to this day, having been married for over 20 years and having raised three beautiful women. I now share this sentiment with my teenage son.

At 13, you showed me that you are more than just music.

You are a message.

Credit: Natrice Miller

Credit: Natrice Miller

Amazed and terrified by the flow of an artist being dollied down a prison corridor and rapping about prison life, I was definitely motivated to stay out of trouble.

Whether it was artists like L.L. Cool J, Queen Latifah or Tupac, I’ve relied on hip-hop my entire life for discovery.

Tyson Horne: Nothing less than a mutual love

Dear hip-hop,

I remember staying up late in the ‘80s to listen to you on WBLS-NY with Mr. Magic & Marley Marl’s “Rap Attack.”

“Krush Groove” showed me how to be like you, walk like you, talk like you.

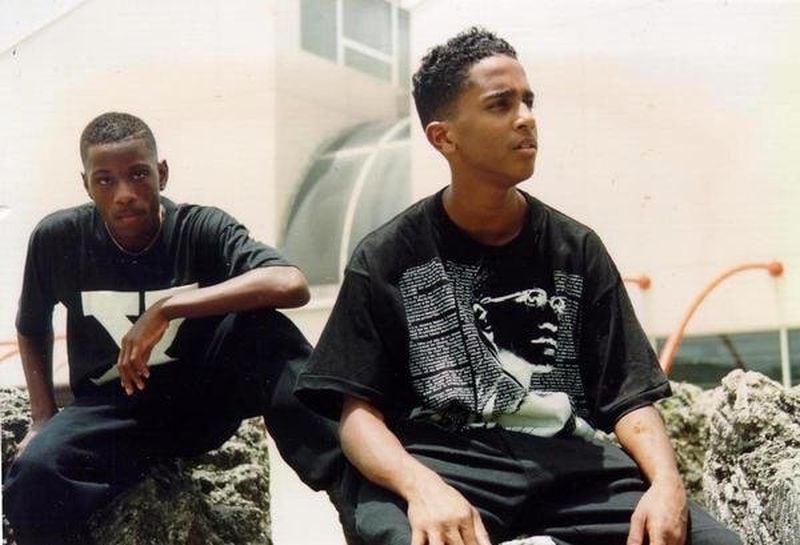

Credit: Tyson Horne

Credit: Tyson Horne

I wrote rhymes down during class when I should have been studying. I worked hard after school to afford the shoes and tracksuits to impress you.

I would buy records and race home on my bicycle with albums under my arms to understand you.

When they told me I could perform with you at the high school talent show I was there — mic in hand. You would have thought I was signed to a record deal the way the crowd went crazy.

Credit: Tyson Horne

Credit: Tyson Horne

That feeling I felt was nothing less than a mutual love.

After that night I knew I would never leave you and I knew you would never leave me.

Life happened and plans changed but I never left you.

Now, I am an older man with gray hair and bad knees.

But I remain funky-fresh just like you.

“Tougher than leather” and I won’t stop until I’m “Paid in full.”

Credit: Tyson Horne

Credit: Tyson Horne

I love you hip-hop.

Happy 50th.

Ernie Suggs: Power in the Moments

In the fall of 1988, I received a letter informing me that I would be accepted for consideration to pledge Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc.

Three months earlier, a group out of New York City called Public Enemy dropped the seminal, “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back.”

I mention that because 11 of us, all students at North Carolina Central University, received those letters. And throughout the arduous process, which would go on well until 1989, we spent all of our time listening to what we all now call simply, “It Takes a Million...”

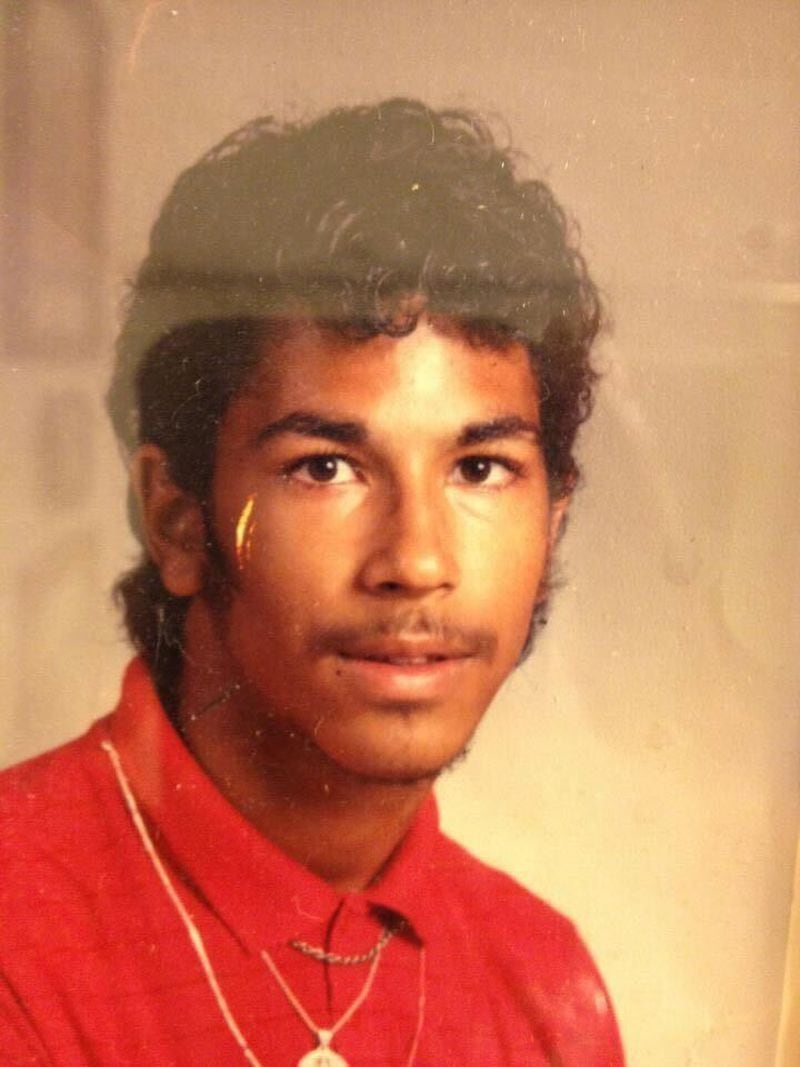

Credit: Ernie Suggs

Credit: Ernie Suggs

Eleven brothers, “bruised, battered, and scarred but hard,” as Chuck D. railed. In the end, when it was time to pick a name for our line, we became “The Prophets of Rage,” the fiery anthem at the end of the album’s “Side Black” to symbolize our journey together.

That period of time is not when I fell in love with hip-hop, but it was the exact moment when I knew that I would be with her forever.

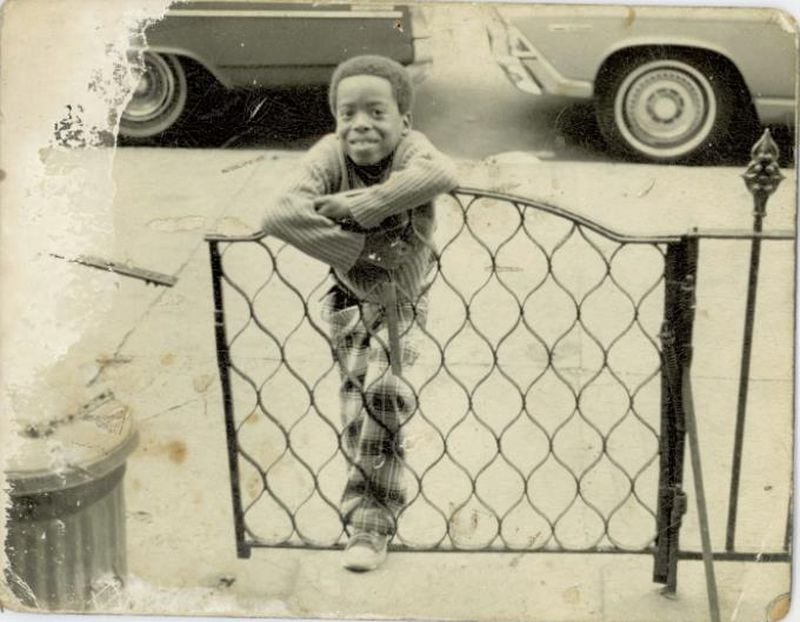

See I grew up in New York City in the 1970s, when rap was becoming the homegrown American art form that jazz became nearly a century earlier.

I could never figure out how they got the power from the light poles. But at our neighborhood block parties, guys with names like Speedy and Rock Head would hook up their turntables and speakers to the poles and steal power from ConEd.

And with it, power a new movement.

Credit: Ernie Suggs

Credit: Ernie Suggs

By the time I moved to North Carolina, I was already in love. I looked on in amusement at all of these country people going crazy over “Rapper’s Delight,” after I had seen and heard similar and better for years at my block parties.

But before “It Takes a Million...” there were two important moments.

The first came in 1983 when Run-DMC released “Sucker M.C.’s.”

My God. I was in the 10th grade. Nerdy and thinking about college, but trying to be cool and athletic. DMC’s closing bars, which he would later tell me were the first ones he ever put on wax, still make me emotional. (And no I didn’t almost cry when I told him this).

“I’m D.M.C. in the place to be / I go to St. John’s University

And since kindergarten I acquired the knowledge / And after 12th grade I went straight to college”

Wait, the hottest rapper in the world was in college? And he wore those thick glasses, “so I can see?”

That was the first time — but not the last — that a rap song had actually spoken to my condition.

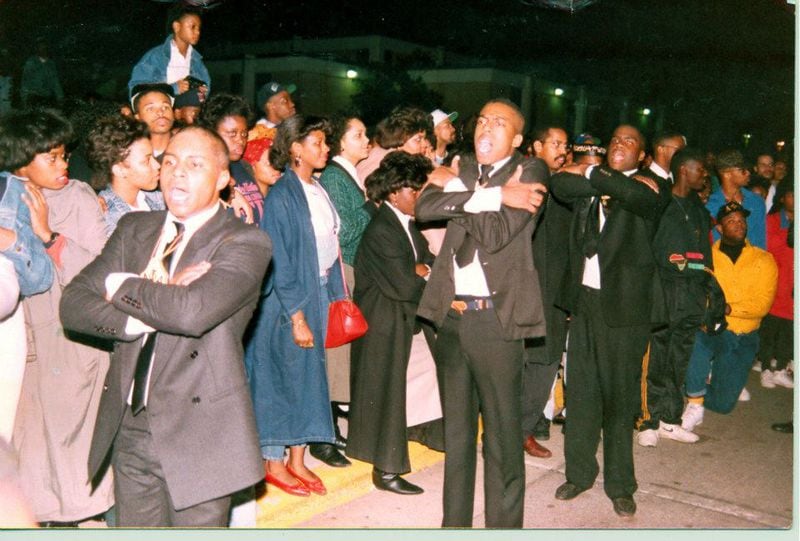

Credit: Natrice Miller

Credit: Natrice Miller

Two years later, I was in college when the second moment happened.

On Aug. 13, 1985, just five days before I arrived on NCCU’s campus as a freshman, Doug E. Fresh and MC Ricky D (Slick Rick), dropped “La Di Da Di.”

Rap was still basic and experimental, so this new human beatbox thing that Doug E. was doing was crazy. We would lose our minds in those old Sweat Box jams on campus when this song came on.

It was wild because we would all run to the dance floor and kind of wait and get ready for 50 seconds during Slick Rick’s intro. Then, when Doug E. hit us with that beatbox, the legendary Sweat Box lived up to its name.

Credit: Ernie Suggs

Credit: Ernie Suggs

I was born into hip-hop, grew up with it and watched it mature into a grand dame of 50.

My roots are still in New York, but having lived in Atlanta for 26 years and witnessing how Jermaine Dupri, T.I., Goodie Mob and OutKast have advanced the sound of hip-hop and taken it places I could never imagine from those block parties, my love will be everlasting.