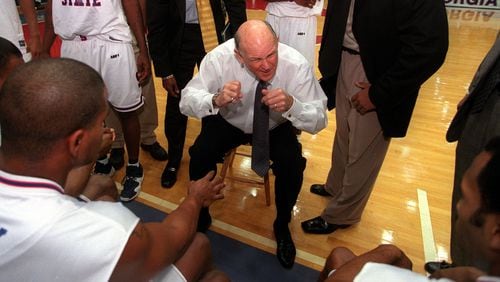

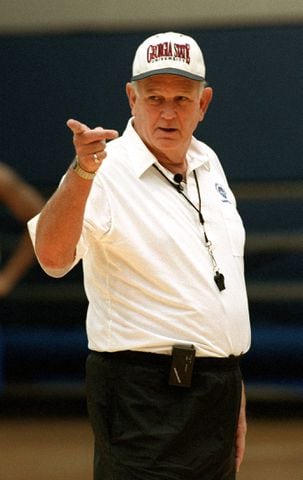

It was six days before Selection Sunday, two days after Georgia State lost the 2002 ASUN final by one point. Lefty Driesell was on the line. “You’ve got to help me get in this tournament,” he said, knowing such assistance was beyond this correspondent’s modest powers. Even legendary coaches get frazzled in March.

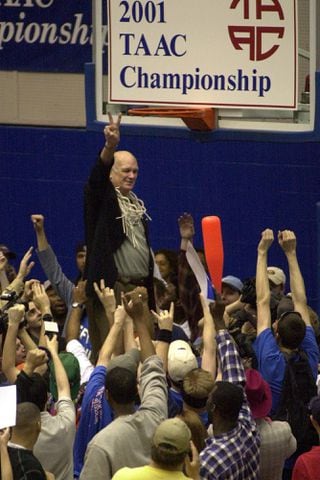

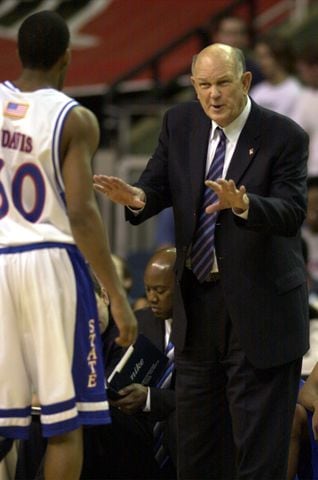

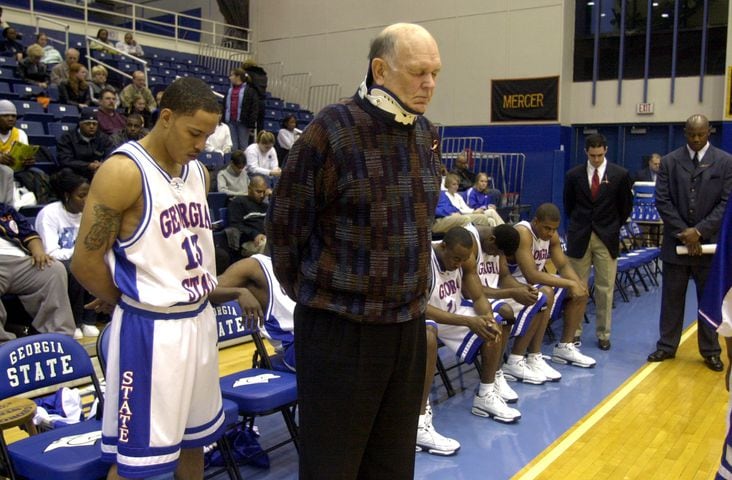

Lefty was then 70. His place in hoops history – he cut his widest swath when the sport was outgrowing its status as a regional concern – was secure, but he wanted one more Big Dance. He’d taken four programs to the NCAA Tournament, Georgia State having made it the previous spring. Those Panthers made big noise by upsetting Wisconsin in Round 1 and playing Maryland, of all teams, tough for 30 minutes.

A year later, Lefty’s GSU finished first in the new ASUN and won 20 games, but he knew that wouldn’t move the selection committee. That’s the worst feeling a coach can have, especially a coach who, once upon a time, was part of one of college basketball’s biggest what-ifs.

His Maryland team of 1973-74 – with Tom McMillen, Len Elmore and John Lucas – opened with a one-point loss at UCLA when Bill Walton was unbeaten as a collegian. Those Terps finished by taking David Thompson’s N.C. State to triple overtime before losing 103-100 in the ACC final. The Wolfpack won the national championship. Maryland went nowhere, 1974 having been the last one-bid-per-league NCAA tournament.

Twenty-eight years later, another Lefty team had come excruciatingly close to a conference title in a one-bid conference. (GSU would lose in Round 1 of the 2002 NIT.) He was on the line to plead his case, but mostly he’d called to talk.

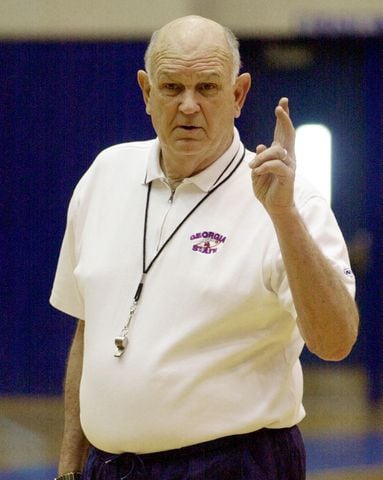

Lefty Driesell died at 92 on Saturday at his home in Virginia Beach. He was famous for many things, not least of them his conversational skills. He could convince just about anybody of just about anything.

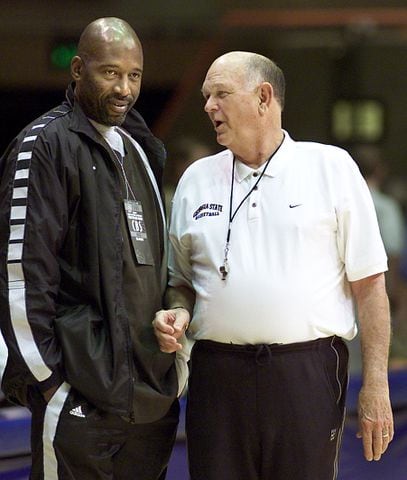

Credit: AJC

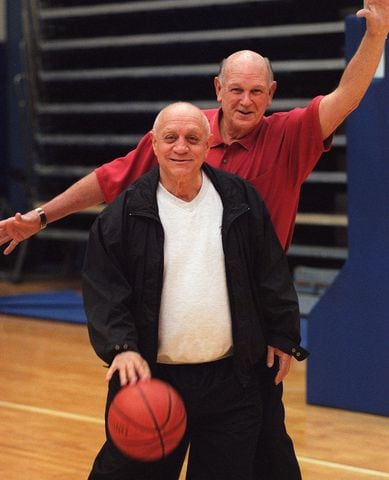

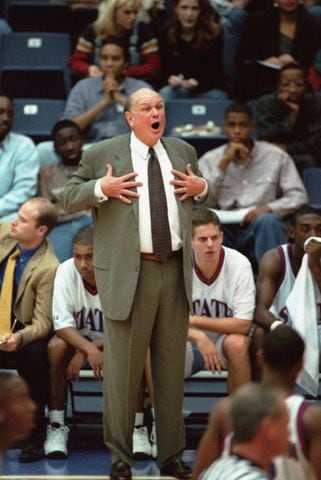

Credit: AJC

He hoisted smallish Davidson into the AP’s top 10. His last game coaching the Wildcats was the 1969 East Regional final, which Charlie Scott won for North Carolina at the buzzer. In 2018, the Naismith Hall of Fame announced it had, at blessed last, chosen Charles G. Driesell for membership. Also among Class of ‘18: Charlie Scott.

Setting up shop in the high-falutin’ ACC, Lefty vowed to make Maryland the UCLA of the East. He came darn close. He lured Elmore from New York City’s Power Memorial. He landed the nation’s top recruit after a chase that ended only when McMillen enrolled in College Park, Maryland, and not, as was expected as late as that morning, in Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Lest we forget, Lefty almost had Moses Malone, who chose the ABA’s Utah Stars instead. Lefty’s immortal line as the teenager was rethinking his college commitment: “Don’t jive me, Mo.”

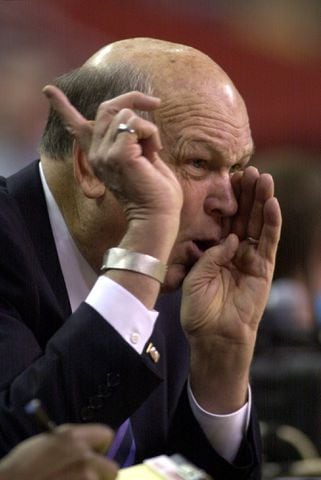

;Lefty was a big man – at 6-foot-5, he played center at Duke – with a bigger presence. His voice, once heard, could never be forgotten. (Everybody who covered college basketball did a Lefty impression.) He had the drawl. He wasn’t a fan of the unexpressed thought. After finally winning the ACC tournament, he said he’d tie the trophy on his car and drive around North Carolina saying, “Ah kin COACH.”

His stay at Maryland ended badly. Looking to blame somebody for the overdose death of Len Bias, the university pushed the coach aside. He surfaced at James Madison. His final coaching stop was here, where he took to promoting his modest Panthers in grand Driesell style. They rose to their moments, posting the school’s first NCAA Tournament win and, not incidentally, twice beating Jim Harrick’s Georgia.

In 2018, on Final Four Saturday in San Antonio, Driesell was introduced as a Hall of Famer. He was in a wheelchair, a grandson doing the pushing. Having suffered Hall disappointments before, the family was as much relieved as delighted. Said grandson Ty Anderson: “It would have been a tragedy for him to have been elected posthumously.”

Anderson is assistant coach at Wofford. At Atlanta’s Holy Spirit Prep, he coached Anthony Edwards, now an NBA All-Star. Anderson’s mom became a Presbyterian minister, which also seemed fitting. Along Tobacco Road, her dad was known as the Preacherman. Because, Lord have mercy, the man could talk.

In the overheated world of ACC basketball, that man became the exception. In the days before conference expansion, these jammed-together schools hated each other. Thing was, nobody could hate Lefty. Any minute with him was a good minute. I got lucky. I got to spend several minutes with Lefty Driesell.

About the Author