Note: This article originally ran on June 7, 1989 as part of the AJC’s award-winning “Suffer the Children” series.

Michael Steven Harmon was raised by a cold and unforgiving parent.

The kind who placed him with strangers when he was just 4, then had him locked up as a teenager. The kind who would meet him at school with his life's belongings in a paper sack and the news that another family wanted to "try him out." The kind who never bought the child a baseball glove or a school picture because it cost too much. The kind who warned caring adults not to shower love on Michael because he might get attached. And the kind who, when he finally grew up and fathered a child of his own, took that child from him and gave it away, telling Michael he was too damaged to make a fit parent.

» "SUFFER THE CHILDREN" SERIES: Full series | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7

PART 4 OF THE SERIES:

Michael, 19, was raised in foster care. His parent was the state of Georgia.

Today Michael - along with thousands like him - stands as testament to a foster care system that frequently doesn't work. It is a system intended as a temporary solution but one that too often becomes permanent. It is one that is supposed to offer a haven to child victims of physical and sexual abuse but too often victimizes them further.

In Georgia, the foster care crisis has spawned living situations for children that are sometimes worse than those reserved for the state's prison convicts. With too few foster families for a growing number of abused and neglected children, foster care for some Atlanta children means sleeping on floors at lice-infested emergency shelters, the latest dumping ground for the children nobody wants.

One recent night, the Fulton County Emergency Shelter - built to handle 30 children for up to 72 hours - housed 86, including some who have lived there for months and one retarded boy who lived there almost a year. A third of the children were babies, sleeping two to three in a crib.

Other babies are being warehoused in hospitals - sometimes by parents who abandon them, sometimes by social workers who have nowhere else to put them. Atlanta's child welfare workers increasingly have difficulty finding foster parents for perfect babies, let alone damaged ones. And in the face of AIDS and the cocaine epidemic, the damaged ones are on the rise.

Of the 6,725 Georgia children in foster care as of last month, 76 percent of them were there because they were physically or sexually abused, neglected or abandoned - in the majority of cases by their parents.

Once in foster care, many children are victimized again. According to the Georgia Department of Human Resources, last year there were 88 confirmed reports of children abused in foster care. One national study puts the rate of abuse among foster children at 10 times that among children in the general population.

Those who are not physically abused are often emotionally bruised by a bureaucracy that bounces them from home to home or from institution to institution.

Raised in rejection, people such as Michael lack self-esteem, have difficulty forming trusting relationships, and worse.

"What you have is a situation where we as taxpayers are incubating tomorrow's criminals in the name of saving children," says Robert L. Woodson, president of the National Center for Neighborhood Enterprise in Washington, D.C. He estimates that 30 percent of children who experience multiple moves before the age of 8 wind up in the nation's jails as adults.

"The problems are circular. It's like building a hurricane."

Michael's life has been such a storm.

'I Didn't Know Where I Even Came From'

No one knows precisely how old Michael was when his mother, an alcoholic, gave custody of her son and his five brothers and sisters to the Clayton County Department of Family and Children Services. Michael thinks he was around 2. Social workers who knew him say maybe 4.

His life's record - stored for years in Clayton County, then moved with Michael to Gwinnett County - has been destroyed. It is most counties' policy to get rid of the records three years after a child leaves their custody. There's just no room.

For many years, Michael didn't even know he had brothers or sisters. Like 40 percent of the children in Georgia's foster care system, Michael was initially separated from them.

"At first, I didn't know nobody," he said in an interview earlier this year. "I didn't know where I even came from."

His first memory as a child is wishing he had a family of his own. "I had friends, you know. I'd see their families."

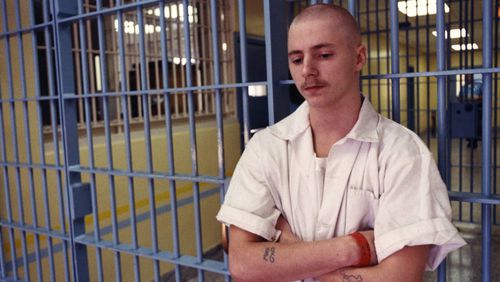

Michael has straight blond hair, blue eyes and the words "love" and "hate" tattooed across the backs of his fingers. The father of two children, he looks like a child himself with the soft peach fuzz of a boy at puberty. When he talks about being raised by the state, he speaks softly and matter-of-factly. He does not complain about the only life he's known.

"Most of them was pretty good," he said of his many foster parents, dragging smoke from a Marlboro cigarette. Then he added, "It's just whoever wants you gets you. That's all it amounts to. If they don't like you, they call up somebody and they come and get you and take you somewhere else."

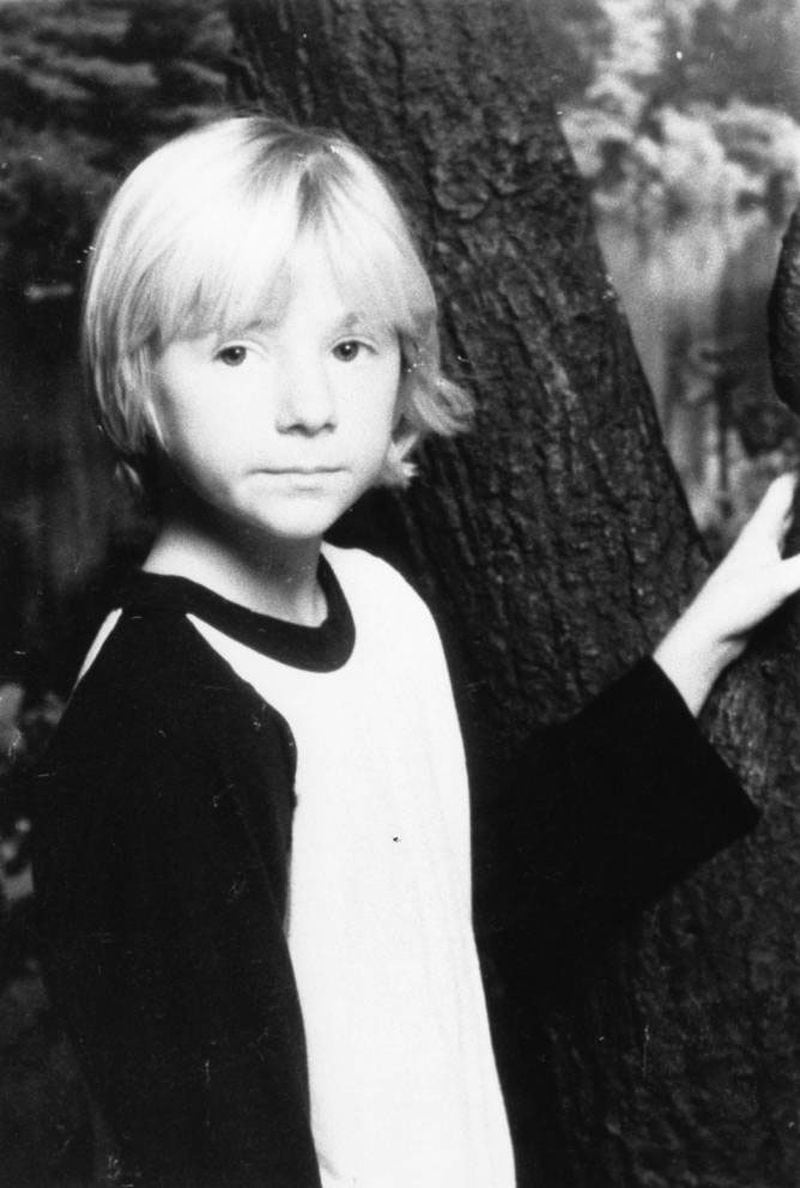

One day, when he was about 8, a social worker came to the elementary school where Michael was a student. He was living at the time with a family he can't remember now, and she brought his belongings to school in a paper bag. As Michael recalls, she told him that a new couple "wants to try you out for the weekend."

It was during the Christmas holidays, and the couple wanted to take Michael to Minnesota where their family lived. He didn't want to go. "I was crying," he recalled. "They told their people that I was their son and everything."

When they returned to Georgia, the couple gave Michael back to the county. "They didn't want me no more."

'You're Not Actually No Family'

In most of Michael's homes, he was not the only foster child. Sometimes he shared a room with as many as six other children, and it was not unusual for the orphans to be relegated to a separate table from the family during mealtimes. In one home, Michael and the other foster children slept and ate in the basement while the husband, wife and their children lived upstairs.

When he was about 4, he remembers sitting in a highchair most of the night because he refused to eat a bowl of coleslaw. One foster mother, the one he liked the least, fed him tomato sandwiches three meals a day. "I hate tomatoes now," he said.

According to Michael, that same woman broke the arm of another foster child, Jamie. "She used to have a big ol' paddle," Michael said. "It was in the summertime. Jamie was about 12."

But whenever child welfare workers visited the home to check on the children, no one spoke up. "Everybody was scared to say anything. We knew when they left, she was the same old person."

According to the county, the woman is no longer used as a foster mother. Today, Michael believes most of his foster parents were in it for the money. (The state pays foster parents $10 a day for each child they take.)

"You're not actually no family. You're there simply because they're getting something for you," Michael said. "Kids don't know that. The only reason I know it now is because I look back and I know what they did. I didn't back then. I didn't know why they was treating me like that."

The hardest thing was living up to each family's expectations. "See, when you go into a home, these people already got their mind set on how they want you to be," he said. "I went to some foster homes where all they wanted me to do was study books and stuff like that. I just didn't like going in there because you didn't know nobody. They just showed you where your room was at. It was like the Army or something. That was where you were stationed. You'd go to sleep at night and you didn't know if somebody was going to come and get you at 3 in the morning and bring you somewhere else."

Credit: Johnny Crawford / AJC file

Credit: Johnny Crawford / AJC file

A Baseball Uniform, School Pictures

By the time Michael was 11, he'd been in at least seven foster homes, according to Beverly S. Read, one of Michael's former foster mothers and the only one he still sees.

When she got him, Michael was an angry, sullen child who was doing poorly in school. He cried most of that first day at her house in Jonesboro. County social workers had made him leave his dog, "Little Bit," at his last foster home. And he didn't understand why yet another family he'd been living with - a military man and his wife - had given him back to the county.

"Michael was in a home that he had felt comfortable in," Mrs. Read said. "But they were not comfortable with Michael. They were military, didn't have any babies of their own. They wanted babies, which 90 percent of the foster care parents want. But rather than sitting down and explaining that to him, the county just picked him up and moved him. What did that do for his self-esteem? He felt that he'd done something wrong. He told me over and over again, 'I didn't do anything wrong. I was good. I tried real hard.' "

When Mrs. Read first got him, Michael lied a lot, particularly about the food he foraged and stored in his room. "He'd get up from the table and take biscuits and put them in his drawers," she said. "I don't know what it is with foster children, but they have this overwhelming desire to hide food. Ask any foster parent. I guess they don't feel they'll get enough. And I would get aggravated. I'd say, 'Michael, you can have as much food as you want, but don't take it to your room.' It was funny until you found a 10-day-old peanut butter sandwich upstairs."

That year at the Reads', Michael gained a full year and a half at school. "He was stable," Mrs. Read said. "He knew we weren't going to let them move him, and that we'd fight if they tried. I told him that, that I'd do everything. And it made a big difference."

At night, she tucked him in, kissed him good night and told Michael she loved him. He told her he didn't believe her.

One of the happiest times of Michael's childhood came that year when he played on the baseball team. "He could run like the wind," Mrs. Read said. "There was no one who could catch him when he ran."

At first, the county Department of Family and Children Services refused to pay for his baseball glove and uniform. "I had a fight with them," she said. She eventually got them to pick up the tab for the uniform. "They didn't want him to have any stability like that. They gave the argument, 'What if we have to move him?' "

The Reads, who have their own trucking business, also bought Michael his first school picture. School pictures are an unallowable expense for foster parents, one that cannot be charged to the state. As a result, many foster children never get them.

The team lost every game that season. But Michael, a fifth-grader at the time, didn't care. "I was there, my husband was there," Mrs. Read said. "We were clapping and cheering him on. He was doing something, and for the first time in his life, he could show the other kids that he had some place to call home. He didn't care that they lost, just so he was a part of it."

The year and a half at the Reads' was an oasis for Michael. It ended when his father came back into his life.

Mrs. Read believes the county nagged Michael's father into taking his son back. "I think they were just tired of messing with it."

Michael was ecstatic. "I always wanted to be with my people," he said. "I'd see Beverly's family and everything, and I'd wonder what it would be like if my family was still together. But it wasn't like what it was supposed to be."

Michael cried the day he left Mrs. Read's. So did Mrs. Read. "We all cried," she said. "My boys gave him something, each one. They were upset. Everybody was upset. Michael had mixed emotions. He was happy about his father, yet torn. I told him I hoped everything would work out OK and to keep trying in school.

"I always told him that," she laughed. "He hated it."

Credit: AJC file

Credit: AJC file

'I Just Didn't Care Anymore'

She didn't hear from him for almost four years. Michael lasted with his father in Gwinnett County for six months. Then the father, an alcoholic like Michael's mother, gave him back to the county.

After that, said Michael, "I just didn't care anymore."

For the next four years, he was in and out of trouble - stealing bicycles and cars, skipping school and running away from foster homes. Eventually he wound up serving time in the state's youth prisons, called "youth development centers." He spent eight months in the Augusta YDC after running away from the Atlanta YDC.

"There was nobody else in there for running away," he said. "They just run out of places to put me."

Law enforcement officials remember Michael well. "I wouldn't trust him as far as I could throw him," said one who wants to remain anonymous. "He is manipulative, not to be trusted and in general, uses any means available to further his own gain."

Said another: "Michael brought on a lot of the problems himself."

During his early teen years, Michael lived periodically with the Gwinnett County probation officer assigned to him. A woman in her 30s, Patricia Wheeler was arrested by Gwinnett County police in 1982 and charged with contributing to the delinquency of a minor after she and Michael were found in bed together, according to law enforcement officials. Michael said she wanted to marry him. He was 14 at the time.

"As I started getting older, I started getting worse," he said. "If she didn't give me what I wanted, like money or something, I'd hit her and stuff like that. I always was getting in trouble. She let me do anything I wanted to do."

Ms. Wheeler was subsequently dismissed from her job because of her relationship with Michael, law enforcement officials said. After the couple spent some time in Florida, Michael said, she got fed up with his refusal to marry her and bought him a Greyhound bus ticket that got him as far as Tampa. He spent a week living in laundromats before he got enough money to return to Atlanta.

Michael's father hasn't gotten in touch with him since he turned him back over to Gwinnett social workers. "I don't blame him," Michael said. "Deep down I know he really loves me."

He does see his mother. In fact, said Mrs. Read, Michael takes care of his mother, a woman largely dependent on drugs and alcohol, according to Mrs. Read and Michael.

"My mom, she ain't never had nothin'," Michael said. "She don't have furnitur e. Whatever she's got, I gave her. She's just pitiful. I love my mama, you know. I always love my mama, because she's my mama. She's throwed me out when I didn't have nowhere to go before. You know, I was out on the street. She just don't understand what it is."

For Michael, Adoption Never an Option

It was Michael's parents who stood in the way of his ever being adopted into a permanent home. They did not want to give up their parental rights, and in Georgia, those rights are often left intact even if a parent does nothing but send a birthday card once a year.

Increasingly, critics say the rights of some parents are being protected at the expense of their children. Children such as Michael, who could have been adopted when he was a toddler, are instead consigned to "drift" in foster care throughout their formative years.

"If they would at least terminate rights on the younger children, they could save lives," said Mrs. Read. "Michael adopted at 3 would have stood a chance."

Ironically, Congress passed the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act in 1980 to cut back on the unnecessary placements of children in foster care. Under the law, states must make "reasonable efforts" to keep families together.

Now critics say the law has gone overboard, keeping families intact at the expense of children's lives.

Michael believes his life might have been different if he'd been adopted early on, before he grew old enough that his only goal in life was to find "my people."

"Yeah, I don't believe I'd be like I am now," he said last winter, his head down as he sucked periodically on his baby's pacifier. "I don't believe I'd ever been in jail. I believe I'd still be in school and stuff like that. I don't believe I'd have tattoos. You know, I probably would have been better off, but I'm happy. Right now, I'm happy. Just me, Carol and my baby."

Foster Upbringing Cited in Custody Fight

On that particular day, Michael was slouched on the living room couch at the home of Beverly Read's mother. Next to him sat his wife, Carol, a pretty 16-year-old with long brown hair and freckles. It was early in the morning, and Carol was drinking a Coke and eating sour cream potato chips, in between cigarettes.

Carol also spent time in foster care, although unlike Michael, she was raised most of her life by her mother, not the state. Both her parents have been in jail, her father for killing a man. The last time Carol saw him was when she visited Michael in jail last summer. According to Carol, Michael was there for driving without a license.

"My husband and my father - both in jail," she mused.

Trouble is in Michael's and Carol's blood, and like recovering alcoholics, they have to work one day at a time to stay away from it. Michael's been arrested at least five times since becoming an adult at 18.

"What got me in trouble was people I hung around with," Michael said.

Both Michael and Carol dropped out of high school in the eighth grade. Michael has worked periodically, but he can't legally drive. The couple would like to live together with their baby, but can't afford an apartment. So Carol lives with her mother, and when he's not in jail Michael lives with his, a woman who spends most of the day in bed, according to her son.

"Michael seems to think that you have to have it all to be productive - the decent job, the home for your family," Mrs. Read says. "And he gets discouraged, because he can't grasp it all at the same time. He wants it so bad, but it's out of his reach."

Carol's mother would like to keep her daughter away from Michael. Almost two years ago, when Carol was pregnant with Michael's first child, her mother put her in the custody of the Clayton County Department of Family and Children Services, after Carol repeatedly skipped school and refused to stay away from Michael. Two days before her baby was due, Carol was placed in foster care.

She says social workers talked her into giving her baby up for adoption. She says they told her if she didn't, she and her baby would be placed in separate foster homes. So she agreed, and under the effects of Demerol less than 24 hours after giving birth by Caesarean section to a baby boy, Carol signed a release abdicating her rights as the mother.

Under Georgia law, she had 10 days to change her mind. While she was in the hospital, Michael rode a bicycle more than 15 miles from Grant Park to Clayton County to see Carol and the baby. He'd been told if he didn't stay away from Carol, he'd go to jail. He never did see his baby.

Carol went directly from the hospital back into the foster home. She says she told her foster mother during the 10-day period that she'd changed her mind. She wanted her baby back. But the law says that has to be in writing. Carol can barely read.

Carol had named Michael as the father, and the county wrote him a letter, informing him that his child was being placed for adoption and it was imperative that he contact them within five days.

Michael appeared at the Clayton County office on the fifth day. Officials acknowledge that Michael was "adamant" about wanting to keep his baby and asked them how he could prevent the adoption. He was told he needed to hire a lawyer to "legitimate" the child, then file for custody.

Michael eventually got enough money to hire a lawyer, married Carol and went to court last July to fight to get their baby back, but their parental rights were terminated. The reasons: She had voluntarily surrendered her rights; he had shown "no interest" in the child and had failed to make any attempts to "legitimate" his baby.

The couple's "youth and inexperience" were also mentioned. And finally officials with the Clayton County Department of Family and Children Services - the agency that had raised Michael - made mention of the fact that he and his wife came from an unstable background and "have in fact been raised in several foster homes."

In courts around the country, parental rights are generally terminated only after it has been shown that a child cannot safely return home. Although one of the five indicators for such a situation is "extreme parental disinterest," traditionally the courts have terminated rights on this basis only in cases where parents have abandoned their children.

'There Are Thousands of Michaels Out There'

Mrs. Read was outraged, calling it another example of how the foster care system had victimized Michael. In a scathing letter that was published in The Clayton Sun, she traced Michael's life.

"Now this former bitter and distrustful child is a bitter and distrustful adult," she wrote, "as beaten down and sad-eyed as any abandoned animal. Where are the people to fight for his cause? Just as we have citizens willing to fight for our abandoned and helpless animals in our county, we need citizens to fight for our abandoned and helpless children in our county. Many of these children are more in danger of being abused or 'abandoned' by the system of the Department of Family and Children Services, Juvenile Court, etc., than if left to their own devices."

In a recent interview, Anne T. Plant, director of the Clayton County Department of Family and Children Services, agreed that children like Michael are sometimes further victimized by the state's foster care system.

"There are thousands of Michaels out there," she said. "Their own mothers and daddies don't want them. How do we expect anyone else to? Unfortunately, they'll be the ones who will be punished later on, rather than the people who did it to them."

In part because of their victimization, she said, Michael and Carol's child is better off with a more stable family. "Here we go with a couple that probably can't take care of this child, not because of their unwillingness, but because they're victims. So they raise that child, and that child becomes a victim. There's no solution."

Michael and Carol didn't know they could appeal the court's ruling in Clayton County. Even if they had known, they don't have the money to hire another lawyer.

Today their first-born is described as a plump, brown-eyed child with brown hair and a double chin. "He's such a happy fella," a county social worker has said. "His smile is so big, it covers most of his face. He is a delight to behold."

Michael and Carol had talked about naming him Joshua. Michael has never seen him. "He's supposed to be adopted right now," he said. "I can deal with that, you know. I mean, he's already gone and everything. If he's adopted out, I can deal with that, but I don't want him to be in no foster homes for the rest of his life."

Yet almost two years after his birth, the child remains in foster care. County officials say they are investigating the possibility of placing the child with one of Michael's relatives. But it is a lengthy process.

Each day that passes puts the baby at greater risk of remaining forever in foster care. People want to adopt babies, particularly white ones. Few want to adopt children.

"It hurts me pretty bad that my son is in there, you know," Michael said. "I think about it every day."

Last October, Michael and Carol had a second son. His name is Joshua. According to Mrs. Read, they have been taking good care of him - keeping up with his immunizations. "There is goodness in him," she says of Michael. "And there is a desperate need in him to someday succeed, to someday make it.''

'My Son Always Has Some Place to Go'

As Michael sat last winter cradling his newborn son, he made a simple pledge. "I won't let my son live the kind of life I do," he said. "My son always has some place to go."

For now, Michael not only can't afford to go back to school, he's afraid to. If he doesn't earn enough money to feed his baby, he's afraid the county will take him away too. "I'm not going to give them people a chance to even say I'm doing something wrong," he said.

As he spoke, his baby cooed. "I believe I can make it if nobody messes with me," he said. "I just want to be happy. I want to get my own place and work every day like normal people. And be happy."

Just Michael and Carol and their baby.

Postscript: On May 9, Michael Steven Harmon pleaded guilty to two separate charges for breaking into a house and breaking into a man's Volkswagen. He was sentenced to serve two years in prison and the remainder of a five-year sentence on probation. Last Wednesday, Michael was transferred from the Clayton County Jail in Lovejoy to the Georgia Industrial Institute at Alto where he will remain for the duration of his prison term. Carol is still caring for Joshua.

----------------------------------------

Georgia's Foster Care Population Keeps Growing

In 1980, the federal government passed legislation aimed at reducing the number of children in foster care. Despite aggressive efforts to comply with the law, Georgia's foster care population rose nearly 45 percent between 1984 and 1988.

The reasons:

Abuse and neglect. In Georgia, reports of child abuse and neglect jumped to 39,100 in 1987, a 26 percent increase from the year before.

Urban housing crisis. In metropolitan Atlanta, as many as 3,000 children are counted among the city's homeless, and the number is growing, according to Anita L. Beaty, executive director of the Task Force for the Homeless.

Teenage pregnancy. Georgia has the highest teenage pregnancy rate in the South, with more than 11,000 teenage births in 1987.

And the more recent specters of:

Drugs, particularly the highly addictive cocaine and its derivative, crack. At Grady Memorial Hospital, the state's largest public hospital, the number of drug-addicted babies has skyrocketed, with more than 200 babies a month now showing positive signs of drug addiction, mostly to cocaine.

AIDS. Georgia ranks 11th in the nation in the number of AIDS- infected children. Currently, Grady is following more than 100 babies who have been exposed to the disease and may or may not get full-blown AIDS. Many were born to drug-addicted parents whose needle sharing led to their own infection of the disease.

Among the results:

As of May 15, 6,200 children were in foster homes in Georgia, but the state had only 3,000 foster homes to take care of them. Another 525 children were in foster care institutions.

Seventy-six percent of the children in foster care in Georgia were placed there because they had been abused, neglected or abandoned by the people responsible for their care. Another 15 percent were placed there because their parents were in jail, mentally ill or addicted to drugs. The rest were put there for such varied reasons as awaiting adoption, being without guardians after the death of parents, or needing supervision that parents no longer could give them.

The median length of time children remain in foster care is 30.8 months.

The average age of children in foster care in Georgia is 10.

Seventy-five percent of the children leaving foster care are returned to their parents or guardians. Another 15 percent are placed with other relatives. Approximately 20 percent of the children who are returned to their parents are back in foster care within a year.

Nationwide, foster care is seen as a permanent arrangement for 32 percent of children in foster care, and 110,000 children have been in foster care more than six years, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. An unknown but significant number of children in foster care are not free for adoption, and no efforts are being made to find adoptive homes for them.