Hilton Fuller passed the Georgia Bar even before he received his law degree from Emory University and started a general practice law firm in 1964 before winning election as a DeKalb County Superior Court judge in 1980.

“He landed in the perfect career,” said his daughter Beth Fuller. “He felt he was part of a team, and he had a job in which he felt like he could make a difference in people’s lives.”

He always did what he felt was right, believing there was a chance at redemption for most people, daughters Beth and Margaret Fuller said.

As a judge, he presided over notable cases in Georgia, such as making a ruling in an early Georgia “right to die” case, overseeing a highly publicized Atlanta gang-rape trial. And he was a judge in the murder trial of Brian Nichols, who made national headlines in 2005 by overpowering a deputy during his rape trail, taking a gun and killing a Fulton County judge and three others.

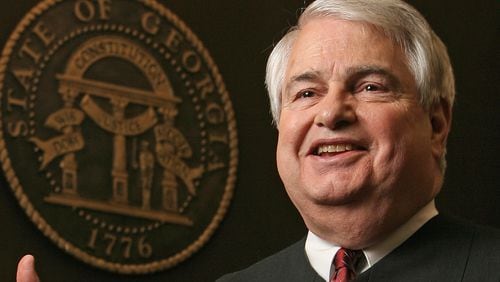

Judge Hilton Monroe Fuller, Jr.’s family was planning his 83rd birthday party when he died on February 14, two days before his birthday, from complications following surgery. A third generation Atlantan, he was the son of Dr. Hilton Fuller, a dentist, and Viola Singleton Fuller, a nurse. He grew up in Ansley Park and played football at Grady High School, while his future wife Peggy Hearn cheered on the team.

“Dad always said she was the love of his life,” said Margaret Fuller. Peggy died in 2021 from the effects of Parkinson’s disease. They were married 57 years.

Fuller attended the University of Florida to play football, but an injury ended his time there. He returned to Atlanta, enrolled in Emory Law School, reconnected with Peggy and graduated from Emory with a Bachelor of Arts and a law degree. Peggy and Hilton married in 1964.The family’s dinner-time discussions often focused on the difference between right and wrong and how justice could be achieved. “Dad liked posing legal questions to us at the dinner table when we were kids,” Beth Fuller said. “We had to opine on them before dinner was served.”

Judge Fuller also served as an adjunct professor at Georgia State’s law school and as a faculty member of the National Judicial College. An accomplished public speaker on matters concerning the judiciary, he thrived in front of a crowd. He also served as President of the Georgia Council of Superior Court Judges.

“When Hilton spoke, the room would get quiet,” said Don Singleton, his first cousin. “He was just brilliant, and people wanted to hear what he had to say.”

Fuller presided over several high-profile cases. He gave a Georgia man suffering with Lou Gehrig’s disease legal permission to have his life-supporting machines turned off. The man wanted to die rather than continue a slow, painful demise to death.

He started the Brian Nichols trial in 2007, but after months of testimony, Fuller stepped down. He had told a New Yorker magazine reporter something he believed was off the record, only to see it appear in the reporter’s story.

Nichols had planned to use a mental health defense that contended that he suffered from a delusional compulsion and couldn’t control his actions. “That’s their only defense, because everyone in the world knows he did it,” Fuller was quoted as saying.

“He recused himself because the story made it seem he couldn’t be impartial,” said Margaret Fuller.

Both daughters said that though their father worked long hours, he never missed a dance recital, a basketball game or a soccer match. He always made time for his children — he would leave the bench to take a phone call from them if they needed to talk.

In retirement, he and Peggy participated in theater productions and found a community of thespians in Highlands, North Carolina. They loved their time in the mountains and the friends they made there. As Peggy’s Parkinson’s progressed, they began spending more time in Atlanta and moved into the Holbrook of Decatur, where they made another strong community of friends.

“If I ever spent the night at home, he would wake me up by singing, ‘Good morning to you,’ to the tune of ‘Happy Birthday,’” said Margaret Fuller. “He was such a softie. He had a wonderful life, and we already miss him.”

In addition to his daughters, Hilton Fuller is survived by his son-in-law John deMoulpied, two grandsons, Timothy and Amir, and nieces and nephews. A memorial and celebration of life will be held at 3 p.m., February 24, at Decatur First United Methodist Church. Donations in his name can be made to the Emory University Center for Ethics-Health, Science and Ethics Program https://together.emory.edu/give/to/centers-and-institutes/center-ethics