These eleven couples, from the United States and beyond, each found their own way of navigating the challenges that interracial couples have faced throughout recent history. Some stories are heroic and others read as cautionary tales. What the couples have in common is a determination to live and love on their own terms.

» RELATED: Georgia interracial couples reflect on the landmark Loving court decision

» RELATED: A timeline of Loving v Virginia

» RELATED: The ‘fake news’ history of the word ‘miscegenation’

Frederick Douglass and Helen Pitts

Married: 1884

The couple: Frederick Douglass was a former slave who became the leader of the abolitionist movement. In 1884, he was 66 years old and widowed, an elder statesman who held the post of District of Columbia's Recorder of Deeds. Helen Pitts was 46, a white suffragist writer and publisher who worked as a clerk in Douglass's office. She helped Douglass write his autobiography.

Their story: Douglass spent a year in depression over the death of his first wife Anna in 1882. When he and Pitts married, the new couple was met with a firestorm of criticism within Washington society and the local press. Their families weren't much better; Douglass' children felt betrayed and his daughter-in-law even sued him. Pitts' family were abolitionists who admired Douglass but some family members couldn't bring themselves to accept him. The couple's closest friends stood by them however. Pitts remarked, "Love came to me, and I was not afraid to marry the man I loved because of his color." Douglass had a cheekier response to the controversy: "This proves I am impartial. My first wife was the color of my mother and the second, the color of my father." The couple were together for 11 years until Douglass' death in 1895. Pitts, against the wishes of Douglass' children, turned his home into a museum and created the Frederick Douglass Memorial and Historical Association. She died in 1903.

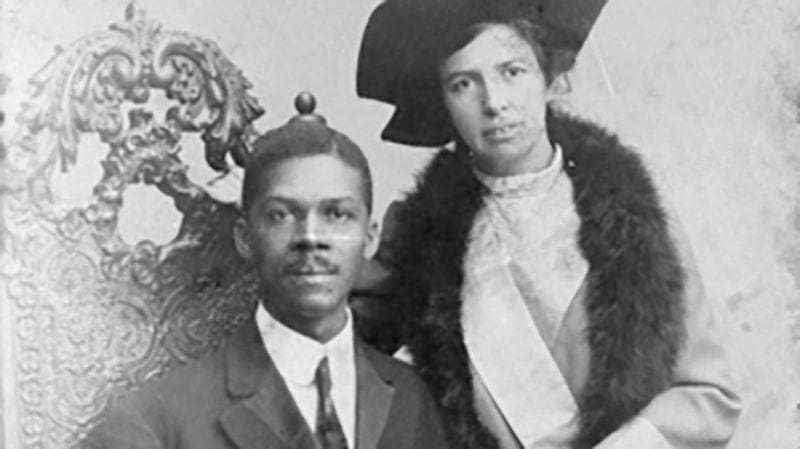

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and Jessie Walmisley

Married: 1899

The couple: Coleridge-Taylor was a mixed-race (Sierra Leone Creole father and English mother) musical prodigy who attended the Royal College of Music. He's remembered as the greatest black British composer and is sometimes called "the Black Mahler." Jessie Walmisley was from a prosperous family. She was a pianist and a classmate at the RCM.

Their story: By the time the couple decided to marry, Coleridge-Taylor was 24 and had just premiered his masterwork "Hiawatha's Wedding Feast." The piece immediately made him an international superstar. Perhaps that gave him the confidence to meet Walmisley's parents at their home in order to lessen the tension with his soon-to-be in-laws. The Walmisleys remained opposed to the marriage but, at least formally, gave their acceptance. The couple sometimes worked together, with Walmisley providing piano accompaniment during performances. Over the next three years, they had a son and a daughter. Coleridge-Taylor became more involved in issues of racial equality and joined the Pan-African Movement, where he became close to W.E.B. DuBois and took an interest in African-American culture. Coleridge-Taylor died in 1912 at the age of 37. His daughter Avril, who became a popular composer and conductor, grew up to have complicated thoughts about her racial identity. A Jet Magazine article from 1955 reported that she lived in South Africa, where she was treated as white and conditionally supported apartheid.

Credit: Library of Congress

Credit: Library of Congress

Jack Johnson and Etta Terry Duryea

Married: 1911

The couple: Jack Johnson, the "Galveston Giant," was the first black world heavyweight boxing champion. He ignored the Jim Crow customs of the time and lived as ostentatiously as he pleased. That included keeping several girlfriends at the same time, some of whom were prostitutes. In 1911, he was 32 years old and was world famous for winning "the Fight of the Century." Duryea was a glamorous Brooklyn socialite who was 28 years old.

Their story: In a 1927 autobiography, Johnson said that early relationships with black women caused him to "foreswear colored women and to determine that my lot henceforth would be cast only with white women." He began dating Duryea in 1909 while juggling relationships with two other white women. According to the Ken Burns documentary "Unforgiveable Blackness," Duryea expected fidelity from Johnson and Johnson became suspicious of Duryea in turn. Their relationship was abusive, and Johnson once beat Duryea so badly that she was hospitalized. One month later, the couple married in secret. As news of the marriage spread, Duryea became isolated and depressed. She took her own life in 1912. Johnson would remarry twice, both times to white women – Lucille Cameron and Irene Pineau. Cameron, who married Johnson only months after Duryea's suicide, stuck with Johnson for 12 years. During that time, Johnson was repeatedly charged under the Mann Act, which made it illegal to cross state lines with a woman for "immoral purpose." (The law was often used to harass consensual interracial couples.) He and Cameron fled the country and lived in exile, and Johnson eventually served time in federal prison. They divorced in 1924. Pineau stayed with Johnson for 21 years until his death in 1946. She said, "I loved him because of his courage. He faced the world unafraid. There wasn't anybody or anything that he feared."

Louisa and Louis George Gregory

Married: 1912

The couple: Louis Gregory, the son of former South Carolina slaves, became an attorney at the U.S. Treasury Department. He is best known for embracing the Baha'i faith and promoting its spread in the southeast. Louisa Matthews was a white British woman also involved in the Baha'i faith.

Their story: Louis and Louisa met in Egypt while on a pilgrimage to the Middle East, where they met the Baha'i leader Abdu'l-Baha. A year later, Abdu'l-Baha suggested that the two consider marriage. Their union was the first interracial marriage in the Baha'i faith, whose message of racial unity is a core tenet. The couple, concerned about "sensational newspaper articles," avoided public attention, Louis said. He went on to become a national leader of the faith and one of its most revered figures, but his work in the South meant the couple would have to spend time apart. Louisa spent much of the year teaching in Eastern Europe and the couple would spend summers together. Louis died in 1951 and Louisa died in 1956.

George Schuyler and Josephine Cogdell

Married: 1928

The couple: George Schuyler was a black Harlem-based journalist known for his conservative views and sharp criticism of MLK. Josephine Cogdell was a white heiress from Texas who was a part-time writer and one-time pin-up girl.

Their story: Soon after their marriage, George published a pamphlet in which he argued that "miscegenation" would cure racial problems in the United States. He and Josephine – often remembered as an excessive stage mother – groomed their daughter Philippa to be a child prodigy in music as a way to prove that mixed-race children were strong offspring. Philippa became a celebrity and had a successful career as a pianist, but she had to assume two identities (one black, one white) depending on where her next concert was booked. Like her father before her, she became a conservative journalist, and was killed in a helicopter accident while serving as a Vietnam War correspondent. Josephine committed suicide two years later. George would live to be 82.

Josephine Baker and Jean Lion

Married: 1937

The couple: Baker was the iconic Jazz Age entertainer and civil rights activist who became a French Resistance agent. In the 1930s she was one of the most famous entertainers in the world and preferred to live in Paris, the city that embraced her. She had been married twice in the United States before her career took off in Europe. Jean Lion was a Jewish French industrialist who was presumably responsible for one of the 15,000 marriage proposals that Baker claimed she received at this time in her life.

Their story: As popular as Baker was in Europe, she was becoming increasingly frustrated by the racism she encountered while on tours of the U.S. After a poor reception to a run on Broadway in 1936 (some reviews were overtly racist), Baker returned to Paris for good. The next year she married Lion, thus becoming a legal French citizen. She also renounced her American citizenship at that time. During the Nazi occupation of France, Baker and Lion were separated but remained married. Baker hid war refugees at her home and conducted spy activities for the Resistance. Despite being the black wife of a Jewish man, she used her considerable charm to deflect the suspicion of German officers. In 1947, Baker married the white French composer Jo Bouillon. Unable to have children, the couple adopted 12 children of varying ethnicity. Baker called them the "Rainbow Tribe," and over the next two decades heavily promoted them (to a fault) as symbols of racial unity. She and Bouillon divorced in 1961 and some of the children eventually lived with him. Baker died in 1975.

Credit: Dennis Royle

Credit: Dennis Royle

Seretse Khama and Ruth Williams

Married: 1948

The couple: Seretse Khama was an African prince studying law in London, next in line to succeed his father as leader of the Bamangwato people. Ruth Williams was an English clerk for Lloyd's of London.

Their story: The couple met in 1947 at a dance and immediately bonded over a shared interest in jazz. They dated quietly for a year, suffering racist reactions from Londoners, before sharing their first kiss and discussing marriage. Their decision to marry caused a series of international incidents. In London, the British government tried to block the marriage (Seretse's homeland of Bechuanaland was a British protectorate) and the couple had trouble finding an officiant. In Bechuanaland, Seretse's uncle, as acting chief, further blocked Seretse's claim to the chieftainship, although this decision was later overturned after a dramatic outpouring of tribal support for Seretse and Ruth. Next door, the apartheid South African government lobbied the British government to stop the interracial couple from assuming power. Britain exiled the couple to London in 1950. They were allowed to return in 1956 after Seretse had renounced the throne. He founded a new political party and in 1965 was elected the country's first president. The next year his country became independent and renamed itself Botswana. With that, the couple became Sir Seretse Khama and Lady Ruth Khama. Khama remained in power until his death in 1980. Lady Khama continued charity work until her death in 2002. The couple had four children – one daughter and three sons – who continue the political dynasty. Their story was recently dramatized in the film A United Kingdom.

Credit: JACK HARRIS

Credit: JACK HARRIS

Pearl Bailey and Louie Bellson

Married: 1952

The couple: They were one of the greatest power couples in music history. Bailey was the black Broadway and cabaret star whose career spanned six decades. Bellson was "the world's greatest jazz drummer," according to Duke Ellington, and was the only white member of Ellington's orchestra for a time. Bellson then became a band leader for the next five decades of his long Hall of Fame career.

Their story: By the time the couple met, Bailey had been previously married four times. She and Bellson knew each other only four days before they married, but it stuck – their union lasted 37 years until Bailey's death in 1990. They wed in London in the hope that they would be better received there than in the U.S., but the union created a stir in the London press anyway. The two became musical collaborators, with Bellson acting as Bailey's musical director. They adopted a black boy in the mid-1950s and had a daughter a few years later. A lifelong Republican, Bailey rarely spoke about race and always espoused a colorblind way of life. As she once put it, "I walk with love and hope it rubs off." Bellson, who remarried after Bailey's death, died in 2009.

Mildred and Richard Loving

Married: 1958

The couple: Mildred Jeter was of mixed black, white and Native American ancestry. She identified as Native American. Richard Loving was a white construction worker.

Their story: Mildred and Richard lived in a small Virginia community with a history of relaxed race relations. The couple first met while they were students in separate segregated schools. Mildred and Richard got married at the age of 18 and 24 respectively in nearby Washington to skirt Virginia's Racial Integrity Act, which banned mixed-race marriages. Despite having a legal marriage license, the couple was arrested and forced to leave Virginia. They moved to Washington and had three children, but eventually moved back to Virginia in defiance of the law. With the help of the ACLU, the couple challenged the Virginia law, which was unanimously overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967. Despite their place in history, the couple avoided the spotlight and rarely gave interviews. Richard died in an automobile accident in 1975 and Mildred died in 2008. Their story has been dramatized several times, including the 2016 film Loving.

Sammy Davis Jr. and May Britt

Married: 1960

The couple: Davis was the boundary-crossing Rat Pack entertainer who lent his presence to civil rights movement events. Britt was a Swedish actress who moved to Hollywood in the late 1950s and co-starred with the likes of Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift.

Their story: When Davis and Britt met in 1959, they were each trying to get out of failing marriages (they would each divorce in 1960). Davis was no stranger to interracial relationships – his ill-fated affair with Kim Novak is the stuff of Hollywood legend and supposedly led to his brief "Hollywood marriage" to the black dancer Loray White. Even while dating, Davis and Britt were met with vulgar racial comments during public appearances and performances. Once married, the couple stayed together for eight years and had a daughter and two adopted sons. According to their daughter Tracey's memoir, Britt stopping acting because the studio dropped her in reaction to the marriage. Tracey's book describes Davis as a loving but absent father who worried about Tracey's life as a mixed-race child in the 1960s. After their divorce, Davis and Britt each remarried in later years. Davis died in 1990 and Britt still lives in California.

Credit: Spencer Platt

Credit: Spencer Platt

Bill de Blasio and Chirlane McCray

Married: 1994

The couple: Today they're the First Couple of New York City. But before Mayor de Blasio's election in 2013, he was a rising municipal politician who served on the City Council and as the city's public advocate. McCray began her career as a black feminist writer and activist, and wrote an essay for Essence magazine in 1979 about life as a black lesbian. She would later become a speechwriter and public-relations consultant.

Their story: The couple met in 1991 while both worked for Mayor David Dinkins—de Blasio as an aide to the deputy mayor and McCray as a speechwriter. As the couple tell it, de Blasio pursued McCray despite her sexual preference, and McCray surprised herself by falling in love. McCray described it this way: “In the 1970s, I identified as a lesbian and wrote about it. In 1991, I met the love of my life, married him.” The couple have two children who often accompany them at public events. The family’s diversity (they’ve been described as “Benetton-esque”) has been the subject of many profiles, some of which describe McCray as a PR-savvy first lady who understands the political value of her family’s story. De Blasio is up for re-election this year.