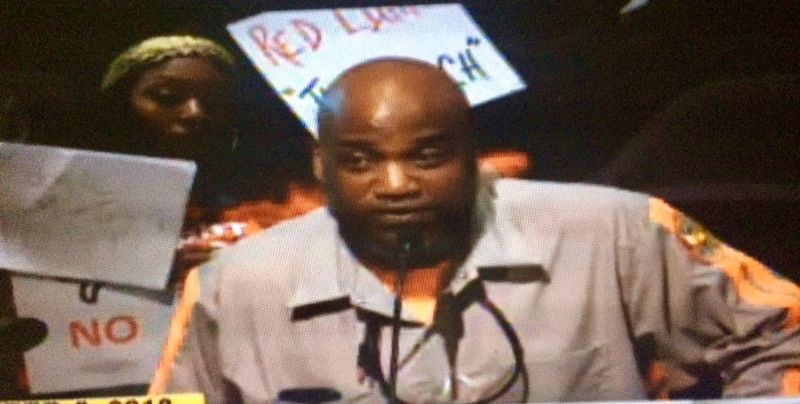

The man in the gray work uniform with reflective orange stripes was a welcome respite at a recent Atlanta City Council meeting.

After hours of droning public debate over the Gulch Tax Giveaway project, Stober Davis walked to the mic and in a deep voice grabbed the crowd's attention: "I'm gonna say rats. I'm gonna say water bugs. And maggots. That's what my business office looks like."

Davis drives a truck for the Atlanta Office of Solid Waste Services. In other words, he’s a garbageman, one of the forgotten foot soldiers in the city’s front-line services. That is, forgotten until they skip your house.

“We do the job no one else wants to do,” he told the council. “We touch the things no one else wants to touch. We’re talking about trash. Your kids don’t want to take out the trash. That’s what we do every day.”

He came to tell city leaders that sanitation workers are underpaid. Guys hanging off the back of the truck make $14 an hour. As a driver, Davis pulls in $16.38. That's $29,000 and $34,000, respectively, much closer to the poverty line ($25,000 for a family of four) than the metro area's median income ($53,500).

The city says drivers can earn up to $44,900 and laborers can earn up to $37,000. Not many stick around long enough to do that.

Davis ended his comments by noting that Martin Luther King Jr. was in Memphis, Tenn., rallying on behalf of sanitation workers when he was assassinated. “Fifty years later, why are we fighting for the same thing?” he said to a round of applause in the chambers.

Solid Waste driver Michael Swift followed, echoing Davis' concerns, adding that he has had a pistol waved at him during his rounds. It was a motorist blocking the street and irate that Swift beeped at her. (That's right, it was a gunwoman.)

Swift said city residents often berate sanitation workers. Folks take their trash and recycling seriously.

The workers came to the council partly because Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms recently announced that cops will get a 30 percent raise over three years. Raise one department’s pay and all others straighten up and notice.

Atlanta police have been underpaid for years and have an awful attrition rate. The pay hike is an effort to keep them.

Trash collectors also have a woeful attrition rate. Now, I get it, keeping cops is vital to any city. And police have a lot more training and more on the line than trash workers.

But garbage workers have a higher death rate on the job than police officers. It's not even close.

I caught up with Davis and Swift a week after their council appearance to ask them about their gig.

On Wednesday, Davis suffered a concussion that required a hospital visit. “A branch caught the truck, snapped back and caught me in the forehead,” he said. He was riding on the back of the truck that day.

The job, he said, beats up workers’ bodies. There’s the lifting, the pulling, the jumping on and off trucks and, it being Atlanta, there’s cars. Lots of ‘em. Trash workers are mostly killed by errant vehicles — drivers who speed around garbage trucks or those who slam into the rear. Often, trash crews are hurried during their routes, which doesn’t add to the safety.

Davis said one of his laborers has been hit. A 2014 city audit found that Solid Waste workers accounted for 18 percent of the city's injury claims. That's an astounding number, considering there are fewer than 200 Solid Waste employees among the more than 9,000 city employees. The city said injuries went up again last year.

Also, the elements can be brutal. Garbage in 98-degree heat certainly has a wang to it.

“And you see the weather last two days?” Davis asked, referring to the torrential rains. “We’re in there starting at 7 a.m. Every day.”

Davis, a single father who is 53, moved to Atlanta from Portland, Ore., three years ago because he’d decided this city might be a good place to work.

His initial glance of Atlanta was weird. “I witnessed things I’d never seen before,” he said. The first route was the Bluff neighborhood northwest of downtown, an area known for poverty and drugs.

“It was walking zombies,” he said. “It was so surreal.”

(Police reading this will argue, “Well, you don’t have to wrestle with them!”)

The city this year moved Solid Waste crews from four 10-hour days to five 8-hour shifts. The move will use fewer trucks, 65 versus 74, and fewer workers, 160 versus 184, according to a recent study this year called “Rubicon Partnership: Service Area and Route Optimization.”

Tracey Thornhill, a 29-year public works employee who heads a union chapter, noted that Rubicon is a computer.

“Rubicon don’t dump no cans; Rubicon don’t drive no trucks,” he said. “By 11 a.m. these crews do more work than any other city employee. Those guys hit the ground running. They need a raise.”

Swift said Solid Waste workers — that includes garbage, recycling and yard waste pickup crews — again asked management for a pay bump after the police pay hike was announced.

“We were like, ‘They’re getting their raise, that’s cool,’” he said. “So we asked, ‘What about Solid Waste?’ They said, ‘No, Solid Waste is broke.’”

The rates for garbage pickup, which haven’t increased in a decade, are being raised — a bit for residents and a lot more for businesses.

Swift, who drives a recycling route and would like to drive for another city department that pays more, said the problem is the Solid Waste department gets little respect.

“We’re the bottom of the pile, the bottom of the pile,” he said.

Still, Swift added, his colleagues “do their work, go home to their kids, and come back the next day and do it all over again.”

The trash, as always, will be there waiting.

About the Author