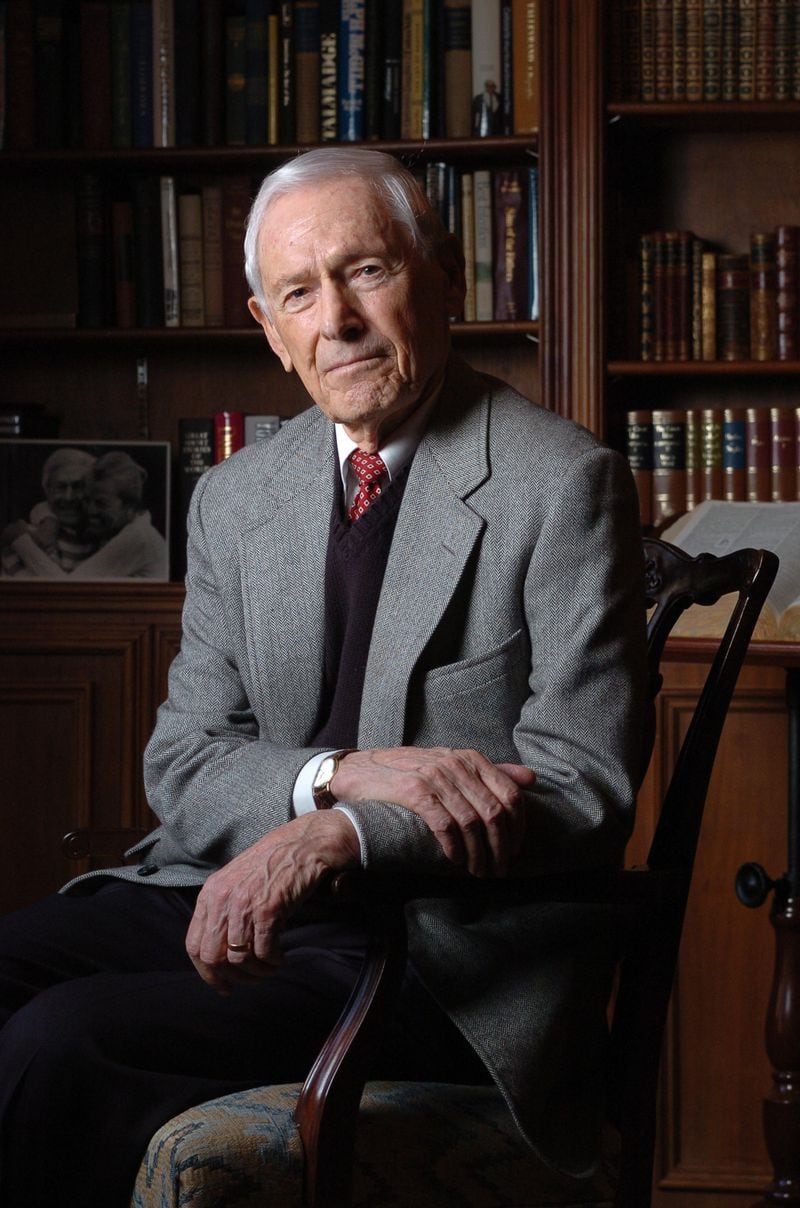

U.S. District Judge Marvin Shoob, who “made the Constitution a reality” in his rulings on Cuban refugees, the Ten Commandments, local jails and hundreds of other cases, died Monday at 94.

Shoob was the embodiment of an independent judiciary in his 36 years on the federal bench in Atlanta. He consistently protected the powerless and downtrodden, notably in cases regarding imprisonment he thought was unreasonable or prison conditions he deemed unacceptable.

“I listen carefully and am guided by the facts in each case,” he said in a 2005 interview. “On human rights, though, you’d have to describe me as liberal.”

Shoob, whose health had been failing in recent months, died at his home surrounded by family members, his daughter, Wendy Shoob, a former Fulton County judge, said. The cause of death was Alzheimer's, she said.

“He was the greatest dad, among all his other accomplishments,” she said.

‘A defining moment in my life’

Marvin Herman Shoob came by his passion for fundamental fairness from a searing World War II experience. Crouching in an artillery shell crater near the French-German border, the young Shoob was surprised when five German soldiers surrendered to him.

A lieutenant came up and asked what he was going to do. “I said, ‘I don’t know.’ He ordered them to lie down, and as they whimpered and prayed, he sprayed them with his automatic rifle. ‘There, that takes care of your problem,’ he told me.”

Weeks later, the lieutenant was killed, Shoob said.

“That was a defining moment in my life and later had a profound influence on my decisions as a judge,” he said. “I vowed from that time forward I always would choose the right way over the expedient way.”

To those who stood before him in court, Shoob was brilliant, bold, uncompromising, rare. He was a believer of America’s best instincts and a defender of its most cherished ideas.

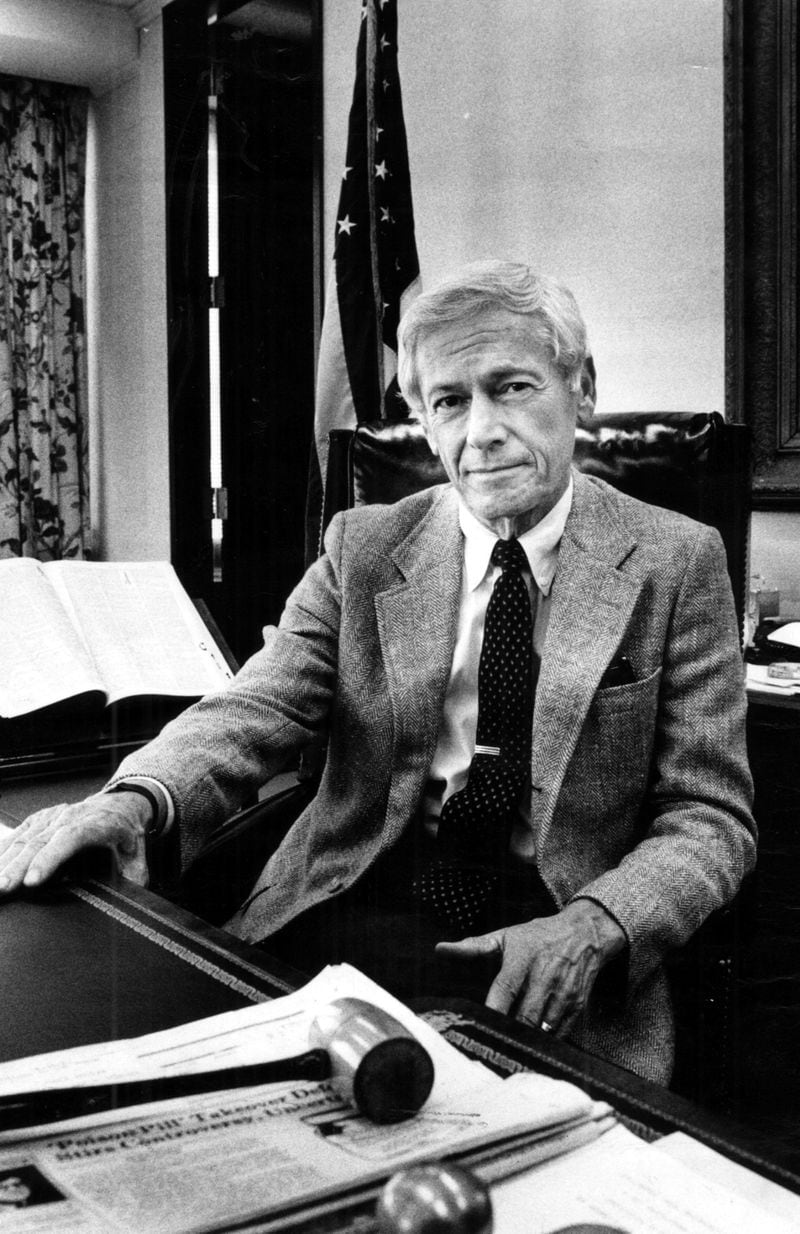

As a judge, Shoob oversaw many high-profile cases and never seemed reluctant to step in and hand down a pointed decision if he thought it was necessary.

He issued a stunning ruling that halted the sensational 1992 trial against James Sullivan, accused of arranging the murder of his estranged wife, a Buckhead socialite. Shoob dismissed all charges before they got to the jury, saying prosecutors failed to make a case. Years later in Fulton County, Sullivan was convicted of Lita McClinton Sullivan’s murder.

Ordering local jail improvements

In 1999, HIV-positive defendants held in the Fulton County jail filed suit, saying overcrowding kept them from receiving essential medical care. Shoob ordered sweeping improvements. To help relieve overcrowding, he required the county and its municipalities to provide lawyers to all defendants within 72 hours of arrest.

In addition to overseeing two class-action lawsuits brought by inmates at the Fulton County jail, Shoob ordered the construction of new jails in Cobb, Douglas and Fayette counties.

“Judge Shoob made the Constitution a reality in places like the Fulton County jail,” said Atlanta lawyer Stephen Bright, who represented the inmates. “He made sure to enforce the rights of refugees or others often denied the protections of the law.”

Shoob long criticized the federal sentencing guidelines, saying they “reduce the role of the sentencing judges to filling in the blanks and applying a rigid, mechanical formula.” In 1988, he declared them unconstitutional, only to be overturned on appeal. He was exultant in 2005 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the guidelines were not mandatory.

Shoob was one of a kind, Atlanta lawyer Don Samuel said.

“He sought the fair, just, compassionate solution to human controversies, notwithstanding the precedents that might compel a more loathsome, unforgiving consequence,” he said.

Shoob, was born Feb. 23, 1923, in Walterboro, S.C., and grew up in Savannah. He enrolled at Georgia Tech but was called up for military service and sent to Virginia Military Institute, earning an engineering degree before being shipped overseas.

Awarded the Bronze Star

An infantryman in Gen. George Patton’s 3rd Army, Shoob saw a lot of combat; at one point, his unit was on the front line in France and Germany for 105 consecutive days before being relieved.

Even then, Shoob bucked authority. In France, he was ordered to carry a large radio up a hill and report whether German tanks were approaching. As he and another soldier began the climb, his colleague was fatally shot in the head.

As Shoob tried to lift the radio, it was hit by sniper fire, so he descended the hill to wait for darkness. But a general drove up and ordered Shoob back up the hill.

“I told him if I did I would be killed and unable to follow my orders,” Shoob recalled. “So, I refused.”

The general sought a court-martial, but Shoob was cleared when his commanding officer came to his defense. After the general left and darkness fell, Shoob noted, he climbed the hill and saw no tanks.

Shoob received the Bronze Star for valor. He hung it on the wall of his chambers next to his most prized possession: a commendation from Patton for the capture of the French city of Metz and the destruction of a German division “under intolerable weather conditions.”

Credit: COPY

Credit: COPY

After the war, Shoob graduated cum laude from the University of Georgia law school in 1948, then moved to Atlanta.

Over three decades, he initially handled mostly civil cases, then branched out to a more general practice.

As a lawyer, Shoob was exceptional, either inside a courtroom or handing out sage advice to a corporate client, said Senior U.S. District Judge Willis Hunt, who practiced law with Shoob in the 1960s and later served with him on the federal bench.

“That made him all the better as a judge,” Hunt said. “He saw things in the light of what good could be done for people who needed help.”

Shoob became a stalwart Democrat and active in the state party’s affairs. In the early 1960s, he and then-State Sen. Jimmy Carter redrafted the party’s rules.

In 1972, he met Sam Nunn, a little-known candidate for the U.S. Senate. Shoob became finance chairman of Nunn’s successful campaign.

On Nunn’s recommendation in 1979, President Carter appointed Shoob to the U.S. District Court bench.

Nunn said Tuesday that he had lost a “friend and a hero.”

“More than anyone I know, Marvin inspired young people to believe that the rule of law is based on fairness for the 'least of these' as well as the powerful,” he said in a statement.

“Marvin taught us all in his sensitive and caring treatment of others – both on and off the bench.”

Most memorable case lands on his desk

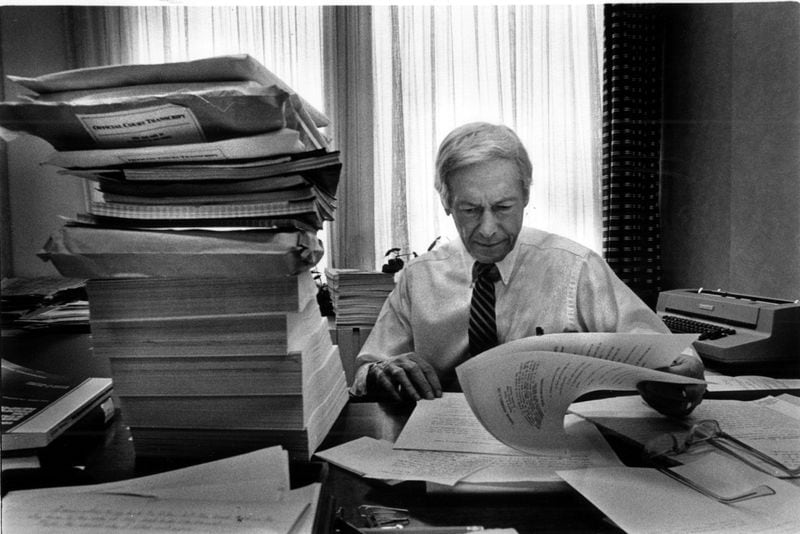

Shoob loved the courtroom. He also swiftly plowed through weighty legal briefs, having mastered the Evelyn Wood speed-reading course.

Not long after becoming judge, Shoob was assigned the case for which he is most remembered — deciding the fate of Cubans who came to this country in the Mariel boat lift and then were detained in the Atlanta Penitentiary.

Credit: W. A. BRIDGES JR.

Credit: W. A. BRIDGES JR.

The first case Shoob heard was filed by a former medical student who had been held in Cuba as a political prisoner. “I let him out immediately,” Shoob recalled. “It made a huge impression on me.”

Shoob would rule that the Justice Department’s position of indefinitely detaining the Cubans in a maximum security prison was “neither fair, reasonable nor humane.”

Thousands of petitions poured in, so many that Shoob hired a half-dozen interpreters to help translate them all. Ultimately, he ordered the release of more than 2,000 Marielitos to Catholic Conference-approved sponsors in Miami.

In a 1981, then-associate U.S. attorney general Rudolph Giuliani publicly accused Shoob of releasing violent criminals.

Death threats — and 15 mailboxes

Shoob immediately received threats. Cars entered his driveway at all hours. He replaced vandalized mailboxes at least 15 times. Two U.S. marshals were assigned to protect him. The FBI monitored his phone calls.

Shoob said he carefully screened all detainees before releasing them. “Giuliani later called me and acknowledged his statement was erroneous and promised a retraction, but it never got the prominence of his original charge,” the judge said.

Over the ensuing years, Shoob received hundreds of “Feliz Navidad” (Merry Christmas) cards from those he freed.

Shoob issued another memorable ruling in 1993, finding unconstitutional a display of the Ten Commandments at the Cobb County courthouse. If Cobb wanted the display, it should include it with other influential documents like the Code of Hammurabi and the Justinian Code, he suggested.

“The Ten Commandments are not in peril,” Shoob wrote in a decision that was upheld on appeal. “They may be displayed in every church, synagogue, temple, mosque, home and storefront. Where this precious gift cannot, and should not, be displayed as a religious text is on government property.”

On Feb. 23, 2016, on his 93rd birthday, Shoob stepped down from the federal bench he loved so dearly.

"It has been an honor and privilege to serve as a United States district judge," Shoob wrote in a letter announcing his retirement. "For this opportunity, I am most grateful."

Shoob’s memorial service will be Friday at 2 p.m. at The Temple, 1589 Peachtree St., Atlanta, GA 30309.

Survivors include his wife, Janice Shoob; a son, Michael Shoob, a Hollywood filmmaker; a daughter, former Fulton County Superior Court Judge Wendy Shoob of Atlanta; and two grandchildren.