Claud “Tex” McIver has carved out a successful career as a prominent lawyer and behind-the-scenes force in the Republican Party.

He is “extremely achievement-oriented,” “optimistic,” “energetic” and, according to an old psychological report, “capable of exerting control.”

Yet he’s the type of person who shouldn’t have a gun, because for a real smart, take-control guy, Tex McIver doesn’t seem to have a lick of common sense when it comes to dealing with deadly firepower.

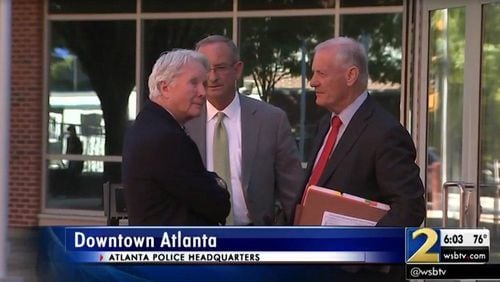

McIver is the lawyer who said he accidentally shot his wife to death last month as they headed home in their SUV. In a shifting story, it seems McIver is afraid of urban crime. So while riding through the mean streets of Atlanta late one night, with a friend at the wheel,McIver had his wife retrieve his gun from the center console and hand it to him in the backseat.

A few blocks later, Diane McIver was mortally wounded. According to his account, Tex fell asleep with the snub-nosed .38 in his lap and it somehow fired. He says he doesn't remember pulling the trigger. Details are sketchy but McIver and his lawyer say it was a terrible accident, which sometimes happens with guns. Happens all the time, in fact.

Sometimes gun owners can thwart off threats. Or they can assume, misread and misreact to a situation with horrible consequences.

Lots of people are scared and a Gallup poll says almost two-thirds of Americans believe having a gun at home makes it safer — a figure that has almost doubled since 2000, even though crime has dropped steadily since.

I mention this because McIver is admittedly concerned about crime and his perception has led to two shootings, the first which damaged an occupied car, the second which killed his wife.

In February 1990, McIver returned home one weeknight to his quiet neighborhood and spotted a parked car with some young men inside. McIver later told the cops he was on edge; he was worried about burglaries around there. So, he did what any rational red-blooded American would do: He sicced his German shepherds on the car and then fired off a couple of warning shots to let them know he meant business.

The intended message worked. The driver threw the car into reverse but retreated into a cul-de-sac. The frightened occupants then decided to drive back out. But that presented another problem. The middle-aged lawyer who had turned into a neighborhood defender had planted himself in the street and, according to police reports, pointed his 9 mm at the car's windshield. When the vehicle — a new Mustang — failed to stop, McIver fired a couple more shots into its rear, the occupants told police.

McIver denied having a gun, both to cops and a psychologist (who came up with the accolades about Tex at the top of the story). The shrink, no doubt hired by Team McIver to impress the judge, wrote that Tex “vehemently and consistently denied he ever had a weapon in his possession.”

Well, maybe a little situational fib.

Some 25 years later, the truth came out.

McIver’s lawyer, Stephen Maples, recently told AJC reporter Craig Schneider that Tex believed the car was trying to run him over and “he had to jump out of the way.”

Why did he fire shots as the car passed him? “Probably fear,” Maples said.

It turned out the three weren’t burglars. They were young guys — yes, they were white — using the secluded street to drink a few beers and toast a friend heading off to the Marines. One of them knew the location well: he was good friends with McIver’s son. In fact, that friend testified in a 1990 hearing that McIver once told him he had no problem with teens coming there, as long as they didn’t leave empties.

DeKalb County police investigated. They found shell casings and even a dog print. Two car occupants told police McIver leveled his gun at the windshield before firing at the passing car. Prosecutors and grand jurors frowned on the shoot-first mentality. McIver got indicted on three felony counts of aggravated assault.

McIver’s lawyer, Maples, the same guy representing him now, pushed back hard in a court hearing. One of the families was close to the McIvers and the teen was clearly troubled by the situation. The driver got ruffled by McIver’s lawyer reminding him that the car’s occupants at first didn’t tell their parents about the beer drinking.

“But does that justify being shot at?” the youth retorted, posing a very understandable question.

In the end, McIver wrote a check for $2,900 to fix the Ford Mustang and the charges went away.

But getting off some very serious felony charges didn’t cause him to head to a smelter with his firepower. He remained armed and worried about crime, ready to address the next threatening situation with deadly force, if need be.

It's not as though McIver is clueless to the inherent dangers of guns. He's written about it, noting that business owners' property rights can trump employees' Second Amendment rights.

“Recent horror stories and logical conclusions suggest that this trend (of allowing employees to pack) is fraught with peril and counteract the “safety” argument that justified the right of the citizenry to carry guns in the first place,” Tex wrote in 2008. “Having a gun within reasonable distance of one’s desk not only allows an employee to resort to violence in a much quicker fashion but also eliminates the “cooling off” period that follows a confrontation or a termination.”

If he only listened to himself.

About the Author