Former students of tennis pro Branch Curington Sr. filed one by one into Curington’s Atlanta home in the days leading up to his death.

They sat beside the hospital bed he occupied, rubbing his arm and telling him how much they love him.

With Curington’s help, most had attended college on tennis scholarships and gone on to successful careers. Some are now tennis pros themselves.

“It was like Grand Central Station,” daughter-in-law Rosalyn Curington said of the crowds that visited. “It was very emotional.”

Branch Curington Sr., 91, a barrier-breaking African American who taught tennis for 50 years and was a member of the Georgia Tennis Hall of Fame, died July 14 of renal failure.

His funeral service will be at 11 a.m. Thursday at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church.

Speaking at the service will be former WSB-TV anchor Monica Kaufman and former Atlanta City Council President Marvin Arrington, two of the who’s who of his many tennis students, his family said.

Curington, a native of Atlanta, quit school after eighth grade to support his widowed mother and siblings.

He always had a strong entrepreneurial streak, relatives recalled. As a youngster, Curington had a shoeshine stand and would charge 10 cents a shine. He would pay his employees – other youngsters – a nickel and keep one for himself, son Branch Curington Jr. said.

At age 13, Curington went to work for Piedmont Driving Club, which at the time was all white except for its employees. He worked in the tennis maintenance department preparing courts for play and as a ball boy. Later, the driving club gave him a job as an assistant tennis pro.

“He did everything in the tennis profession that you could do,” Rosalyn Curington said.

He learned how to build tennis courts and to string tennis rackets.

His racket-stringing would turn into a profitable nationwide business and produce an income for Curington far above what he earned teaching tennis, his daughter-in-law said.

He was the first African-American in Georgia to be certified as a tennis teaching professional, and many of the city’s elite would take lessons from him on their lunch breaks, she said.

From 1964 to 1992, Curington was considered the most influential figure in a burgeoning African-American tennis community.

Under his guidance, prominent Atlantans learned to swing a tennis racket. They included Atlanta mayors Andrew Young and Maynard Jackson, baseball great Hank Aaron, businessman Herman Russell, Arrington and Kaufman.

About 50 players taught by Curington went on to play in college, most notably UCLA’s Horace Reid, also a member of the Georgia Tennis Hall of Fame.

“He was very proud of all of them” and helped many of them go to college on tennis scholarships, his daughter-in-law said.

Atlantan Kelvin Byrd, 54, said Curington was much more than a coach to him.

“He was a second father to me,” said Bryd, who has cerebral palsy.

He said Curington “gave me encouragement from Day 1” and a pair of Jack Purcell tennis shoes before each tournament.

“I’m surviving life in tennis because of Branch,” he said.

In 1964, Curington was approached by Mayor Ivan Allen, who knew him from the driving club. Allen wanted him to run Washington Park’s new tennis center. A clubhouse, grandstand and five additional courts had been built, but the city hadn’t found a true tennis pro to make it successful.

Curington accepted the job. He worked 25 years at Washington Park, and a total of 50 years as a tennis coach, his son said.

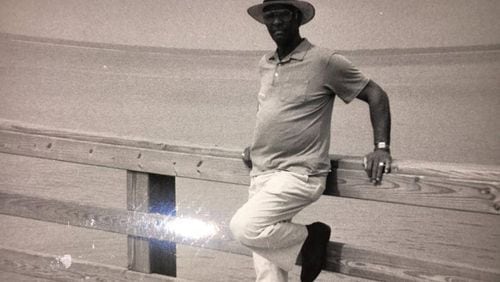

Tennis was his passion, but Curington also liked to travel, his daughter-in-law said.

“He liked going to Hilton Head. He liked the water,” she said. “He liked to give parties in his backyard.”

He was “a people person,” his son said.

Walls at Curington’s home “are filled with just pictures and pictures and awards and awards,” daughter-in-law Rosalyn said.