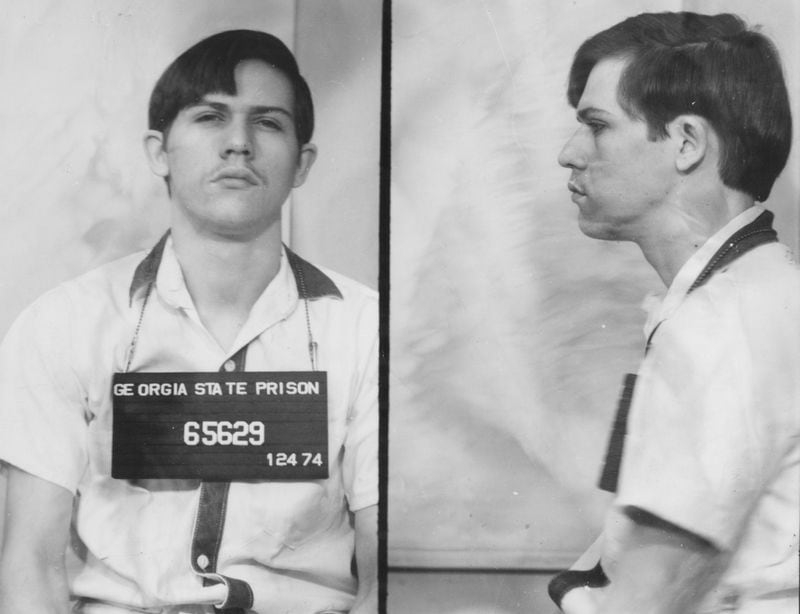

The six caskets of the Alday family sat outside Spring Creek Baptist Church, not far from a cedar tree planted in 1875 by great uncle Ike Alday. The six were the victims of Carl Isaacs, a man who would live another 30 years before being put to death for the murders.

As a member of the media, I was kept about 100 yards from the funeral service. But the distance and the noise of more than 1,000 people who had come to a tin-roofed country church to pay tribute to the farm family couldn’t overcome the sounds of grief from the front rows.

The keening and sobbing of more than 50 family members pierced the humid air that May afternoon in southwest Georgia’s Seminole County, cutting through the choir’s hymns, sailing above the organ’s firm notes.

Three decades have passed, but that sound of pain, of unhealable loss, is what I hear when I write about Isaacs and the Alday killings. It has been there through both of Isaacs’ trials and through the scores of stories I have written about the murders. I heard it loudly last month, as I stood in rainy twilight outside the state’s death-row prison and waited to be told that Carl Isaacs, now 49, had died from lethal injection.

More than Isaacs’ smug impertinence at his first trial, more than the entertaining but sad story of how he conned a lovesick Ohio grandmother into helping him try a jail break, more than his offer of an exclusive story if I would do it his way, I will remember Carl Isaacs as a man who gashed the heart of Donalsonville and Seminole County so deeply that people could only express it through a plaintive cry that May afternoon in 1973.

In Seminole, they say, “If you’re not an Alday or a Johnson, you’re married to one.”

Until day trader Mark Barton killed nine people on July 29, 1999, the murder of the Ned Alday family often was considered Georgia’s most heinous crime.

It began about 4 p.m. on May 14, 1973, when Isaacs, his brother, a half-brother and another man rolled up to Jerry and Mary Alday’s empty mobile home in a stolen car. All but 15-year-old Billy Isaacs were escaped prisoners from a Maryland prison work camp.

Nobody was home, so they burglarized the trailer. Singly or in pairs, men of the Alday family walked up from the fields, perhaps drawn to the trailer by the strange car parked there. Isaacs and his gang shot and killed each of them, execution style, as they arrived. The bodies of family patriarch Ned Alday, his brother Aubrey and three of Ned’s sons were found shortly after midnight. Mary Alday was missing; later her nude body would be found lying in the dirt.

By the following morning, reporters and photographers were swarming along River Road, trying to get a look at the crime scene, and an all-points lookout had been issued for Mary Alday’s blue and white 1970 Chevy Impala.

Dan White, the county sheriff of 21 years, was thinking about what should happen to the killers.

He pulled out his family Bible to show how the Book of Genesis prescribed the death penalty for Isaacs, his half-brother Wayne Coleman and George Dungee. (Billy Isaacs, 15, turned state’s evidence and was not charged with murder.)

“If I had my way about it,” said the sheriff, “I’d have me a large oven and I’d precook them several days. . . . And I don’t think that would satisfy me.” A dozen years later, a federal appeals court cited the sheriff’s words in ordering new trials for the three men.

But many shared White’s opinion.

“I feel sorry for ‘em if they’re caught around here,” said a fellow drinking coffee at the Green Top restaurant. “I don’t think they’ll make it to jail.”

They were caught in West Virginia, five days after the slayings.

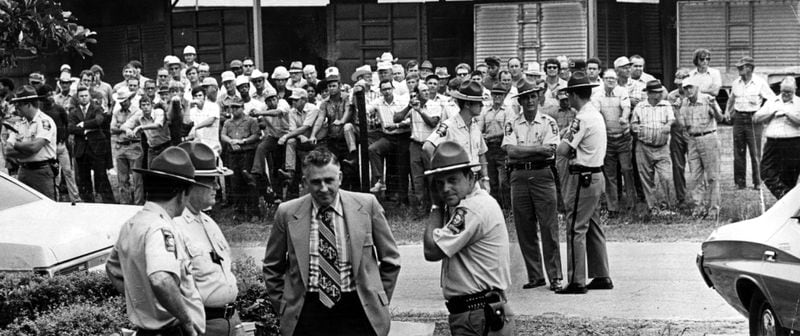

The following Monday, the four men were hustled into the courthouse in handcuffs and shackles for a first court appearance, a GBI agent at each man’s elbow.

Isaacs and his gang never knew how close they might have come to death at the hands of vigilantes that day and how it was another Alday who saved them.

Credit: COPY

Credit: COPY

Calming remark

As the defendants were led up the courthouse steps, nearly 100 grim-faced men stood across the street, their jaws set firmly, eyes fixed in anger.

“Just give the word and we’ll take those boys away from the troopers,” a man told Bud Alday, Ned’s brother.

Bud, a sad-faced paper mill equipment operator, declined.

“Enough people have been hurt already,” he said.

Bud often reconsidered that remark in the 16 years before he died. When Isaacs and his two codefendants won a retrial 15 years after the killings (they were convicted a second time), Bud had had enough.

“If we could relive those days, they wouldn’t have to give them another trial. . . . We would have hung them to a tree,” Bud said.

The first jury trials, in January 1974, were in Seminole County, in a courtroom adorned with the Ten Commandments and the scales of justice. The back-to-back trials lasted less than one week. None of the defendants ever testified. All three were sentenced to death.

The Alday family hired a family friend for $5,000 as a special prosecutor. Former Lt. Gov. Peter Zack Geer of Albany was a hunting and fishing buddy of Ned and Aubrey Alday.

Credit: AJC Staff

Credit: AJC Staff

He was flamboyant in court, his voice booming as he paced in front of jurors, firing questions and shaping their opinions. He was just as flamboyant most nights, when he would knock back package-store booze at a steakhouse where we all had supper, and announce his presence with a bawdy joke and a hearty laugh before he recounted the day in court.

To borrow an old euphemism about imbibing, the special prosecutor was often “in high spirits” at closing time. But the next morning, Geer, lieutenant governor from 1963 to 1967, looked none the worse: eyes clear, hair in place, suit looking crisp, his baritone still strong.

One of his finest moments in that first trial came during his closing argument, as he drew on a colorful definition of murder in Georgia law: “Use your Georgia walking-about sense and tell me if Carl Isaacs has an ‘abandoned and malignant heart.’ "

The jury took 38 minutes to arrive at a guilty verdict.

At the defense table with Isaacs was the late state Rep. Bobby Hill of Savannah, a leader in the House black caucus. Isaacs didn’t want him, and Hill, a staunch foe of capital punishment, took the case only because Willis Conger, Isaacs’ first lawyer, wanted out. “I’d rather take a whipping” than defend him, the late Conger told me.

A petulant kid

Hill wouldn’t let Isaacs talk with media, so during a lunch break, I walked up to the defense table to ask Hill a question. I wanted Isaacs to hear, to goad him into giving me a quote.

Isaacs’ response was curt --- what he said wasn’t worth quoting --- but his tone of voice and manner made him seem like a petulant kid feeling mistreated by having to stand trial for murder.

As witnesses testified, Isaacs usually slumped, looking bored and studying the floor. But his disinterest, feigned or not, vanished when his brother Billy, who had made a deal and pleaded guilty to lesser crimes, took the stand as a prosecution witness.

Billy had the instincts and quick-wittedness of a survivor. He never looked at his brother, except for a brief glance when required to identify Carl for the record. Always referring to his brother dispassionately as “Carl Isaacs,” Billy testified in a flat, expressionless voice, providing the indicting details of how the Alday family died. After that, it seemed it would not take jurors long to reach a verdict and decide on a penalty.

It was during the penalty deliberations that Bud Alday again did the unexpected. Bud walked over to Bobby Hill at the defense table and shook Hill’s hand. He told Hill he wanted him to know the family had no hard feelings, that they knew he was doing his job.

After the verdict and the death sentences, things quieted down in Seminole County. But residents’ outrage and hurt came back in 1985 when the U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals overturned the 1974 convictions; “inflammatory” pretrial publicity and widespread presumption of guilt made Seminole jurors biased, the court ruled.

Back at Lois’ restaurant, patrons were incredulous. Why did Isaacs need a new trial and where could it be held?

“The space shuttle, maybe?” said Bo McLeod, who is still editor of the weekly Donalsonville News. “There’s not a place on the globe that people haven’t heard about the Alday murders.”

One reluctant juror

Three years later, Isaacs and Wayne Coleman were reconvicted. Isaacs was sentenced to death by a Houston County jury. A DeKalb County jury deadlocked on the death penalty for Coleman. In July 1988, state and local prosecutors opted not to retry Dungee, citing a new state law barring the death penalty for the mentally retarded. Coleman and Dungee are serving six consecutive life sentences.

The second death penalty decision against Isaacs was a close call.

A juror fainted in the hot, stuffy jury room, and another had a near emotional collapse. She could be heard from the press room, sobbing hysterically and crying, “I can’t do it.”

When the jury announced its decision, Isaacs’ lawyers asked that jurors be asked individually if they supported the sentence.

Would the reluctant juror change her mind?

One after another, jurors said they supported imposing the death penalty. Then the clerk asked the juror who had been crying whether she stood by her decision.

Looking exhausted and miserable, the woman nodded and mouthed a barely audible “yes.”

When Carl Isaacs, at 49, left this earth on May 6, I was standing under a tarp outside the Georgia Diagnostic and Classification Center in Butts County.

It was raining as a prison official briefed us about Isaacs’ time of death, and the blue ink of my notes seemed to flow off the pages, erasing Carl Isaacs a word at a time until he was gone.

About the Author