Editor’s Note: This story is one in a series of Black History Month stories that explores the role of resistance to oppression in the Black community.

Amy Lotson Roberts has heard the powerful story of resistance at Igbo Landing (aka Ibo or Ebo) since she was a little girl growing up on St. Simons Island in coastal Georgia.

“They call it the end of the world,” said Roberts, a Gullah-Geechee author and executive director of the St. Simons African American Heritage Coalition.

Details of the story about a group of enslaved Africans who rebelled, choosing death over bondage, has survived more than 200 years and been told across generations and across continents from the Black community in St. Simons to West Africa.

Credit: Courtesy Criss Ford

Credit: Courtesy Criss Ford

In 1803, 75 enslaved Igbo Africans, mostly from an area that is now known as Nigeria, were brought to the United States where they were sold to work on plantations along the Georgia coast, according to the National Museum of African American History & Culture.

The enslaved Africans were then put on the York, a vessel headed to St. Simons, when they rebelled. Led by their high chief, they fought the crew and fled into the marshy tidal waters of Dunbar Creek. Some were recaptured or went missing, but between 12 and 15, according to the museum’s website and oral retellings, drowned. Some people believe they chose death as a final act of resistance rather than live a life of bondage.

Credit: Contributed

Credit: Contributed

The story of Igbo Landing has been mostly passed down through oral history, and there are different variations. Opinions differ on whether the drownings were a mass suicide, an act of defiance or an attempted escape gone wrong. Some legends say the water took them back to Africa.

“The Igbos are very strong people,” said Roberts, who can trace her ancestry to Africans who were brought to the coast on a slave ship. “We come from kings and queens. We were wrapped in gold and bronze. They decided this was not what they wanted to do. The water brought us, the water took us away.”

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

There are ghost stories surrounding Igbo Landing, too

Roberts, 75, has heard of people who were scared to fish from the creek because they believed it was haunted with the spirits of the dead Africans. Some claim to have heard the rattle of chains and the moans of the Igbos. Others believe their boats moved on their own, a notion that Roberts dismisses.

Igbo Landing has also become a part of pop culture, said Melissa L. Cooper, associate professor of history of Rutgers University-Newark and author of “Making Gullah: A History of Sapelo Islanders, Race, and the American Imagination.”

Cooper cites the 1983 novel “Praisesong for the Widow,” in which author Paule Marshall writes that a group of enslaved Africans didn’t like the looks of America “so they turned around and walked back across the Atlantic Ocean.”

Igbo Landing provides a significant plot point in Julie Dash’s 1991 award-winning film “Daughters of the Dust” that in turn inspired the imagery in Beyonce’s 2016 “Love Drought” video in which the Grammy-winning artist is seen walking into the water with a line of women behind her.

There are few historical accounts from that period that describe what happened and most are told through the eyes of whites who worked or owned plantations on the island.

A letter dated May 24, 1803, from William Mein, identified as a slave dealer in some writings, to Pierce Butler, a plantation owner who lived in Philadelphia, describes the episode as a mutiny. Transcribed from the collection of Historical Society of Pennsylvania, it describes “a whole cargo of Ibos (that) may have suffered much by mismanagement. ... (T)he negroes took to the marsh + may have lost at least ten or twelve” costing “ten dollars a head for salvage. We know something happened.”

Credit: Courtesy Criss Ford

Credit: Courtesy Criss Ford

Said Mimi Rogers, curator for the Coastal Georgia Historical Society, “The account of Ibo Landing has been called intangible history because some of what we know is based on oral histories that have been handed down through the generations. Since the first half of the 19th century, an area of Dunbar Creek has been known as Ibo Landing. It is not a great leap to connect this with what happened in 1803. The contemporary written account confirms that there was an act of resistance.”

Last year, a historical marker dedicated to the resistance was erected at Old Stables Corner on Market Street in St. Simons Island. The site is less than a mile from where most people believe the rebellion occurred. The actual site on Dunbar Creek is on private property.

For years Amy Roberts took visitors on tours that stopped along Dunbar Creek, which can be seen from Atlantic Drive, but she had to stop when the occupants of the property complained.

That hasn’t prevented the curious and those who want to pay respect. They can drive down Atlantic Drive until it dead ends and look to the left or stand on the small causeway bridge.

Darien resident Griffin Lotson, vice chairman of the Gullah-Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission and a cousin of Amy Lotson, considers visiting the site a spiritual experience.

Credit: Shelia Poole

Credit: Shelia Poole

He described looking out at Dunbar Creek as “almost like having an out-of-body experience. You can feel it. It’s emotional and, for a brief moment, you’re there.”

On one of his visits, Lotson, 68, grabbed a handful of dirt and put it in a plastic container that to this day he keeps at his home.

Lotson said some families don’t like to talk about what happened at Igbo Landing. For a while, he didn’t tell his children.

“It’s the trauma of slavery,” he said.

The story of Igbo Landing is spreading among the Igbo community in the U.S. and abroad, said Dr. Kanayo K. Odeluga, an advisory board member for the Center for Igbo Studies at Dominican University in Illinois. He is working with others to designate Igbo Landing as a national historic site.

Because the Igbo believe life is sacred, he is certain the Igbo died not as an act of suicide but as an act of resistance.

“The Igbo spirit will not be subjugated,” Odeluga said. He imagines them thinking: We refuse to be put under and can only free our spirits when we give it up. By water we came, by water we will return.

“By their actions they were saying to the enslavers, ‘We will deprive you of the pleasure that you get from oppressing and subjugating us. You think you have the power over us, but we are going to deprive you of that power’.”

Today on Dunbar Creek, there is no visible sign of what happened. But not far away, a large painting depicting Igbo (or Ibo) Landing hangs at the Historic Harrington School and Cultural Center, formerly the Harrington Graded School built in 1924 to educate the island’s Black students.

Credit: Shelia Poole

Credit: Shelia Poole

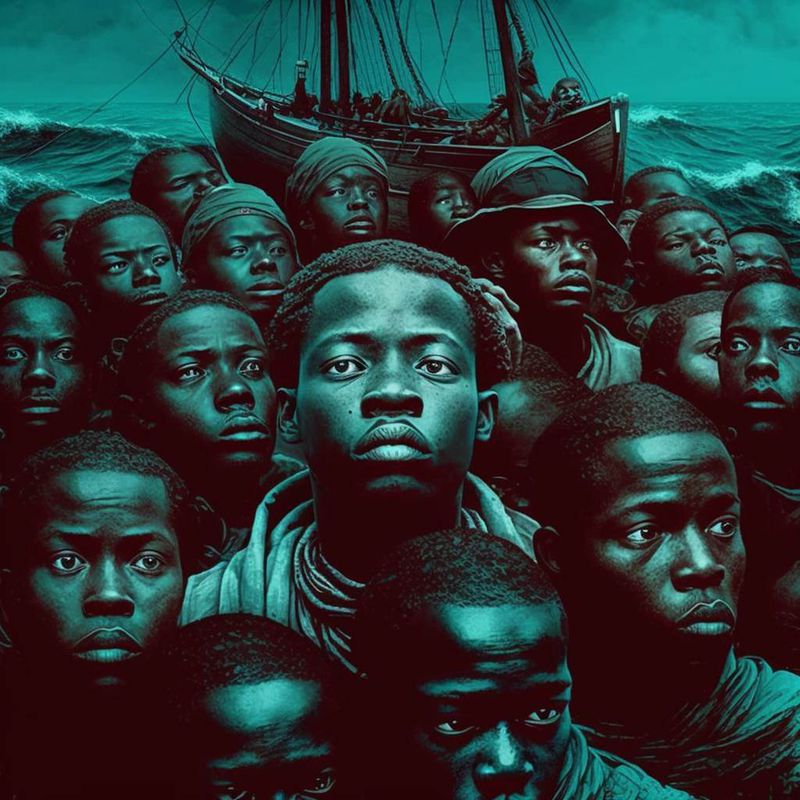

Painted by artist Diane “Dee” Williams, it depicts men and women with chains on their wrists and around their necks clutching each other in the water as a slave ship lurks ominously in the background. Two hands, bound by chains, rise up from the water reaching for the sky.

As manager of the cultural center, Emory Rooks, who can trace his lineage back to Salih Bilali, an enslaved African from modern-day Mali, sees the painting often. It’s a constant reminder that “Being chained all your life and to be a slave, that’s not a good life,” he said. The painting “makes me deeply concerned. It shows how they suffered.”

Credit: Courtesy Criss Ford

Credit: Courtesy Criss Ford

Brunswick resident Helen Ladson is a Gullah Geechee who runs the nonprofit Heritage Works that trains Gullah-Geechee descendants in historic preservation through linguistics, agriculture, culinary arts and the restoration of historic sites. She is introspective about Igbo Landing and its larger implications.

”I would love for this story to speak of the resilience that was there,” she said. “Whatever happened at Igbo Landing is still here within us and still in Igboland and across the world. I want to make sure we uplift and empower. Empowerment comes from a place of strength knowing that their spirit still lives on within us here on the coast.“