Editor’s Note: This story is one in a series of Black History Month stories that explores the role of resistance to oppression in the Black community.

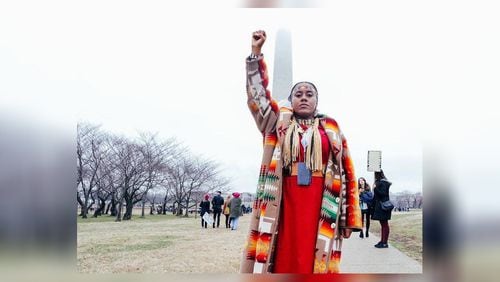

Yonasda Lonewolf’s father is an African American from Brooklyn. Her mother is an Oglala Lakota. They met on a reservation in South Dakota where Lonewolf was born.

“I came from the womb of a Native woman,” says the 44-year-old Atlanta community activist. Still, people have continually questioned her identity as she navigates between her Black and Native cultures.

When she advocates to have Indigenous People’s Day replace Columbus Day, for example, she says she gets hate from both sides. “Native people say how dare I look like me and try to represent all Native Americans. Blacks said I don’t even look Indian.”

Credit: Courtesy Yonasda Lonewolf

Credit: Courtesy Yonasda Lonewolf

Lonewolf embraces her Native and Black heritage and she and others like her want to help younger Afro-Indigenous people understand their own journey and their duality.

Some 270,000 people in the United States identified as Black and Native, according to the last U.S. census.

It’s a complicated relationship past and present, says historian Malinda Manor Lowery, an Emory University professor, and a member of the Lumbee Indian tribe in North Carolina.

“Presently, this is a good time for Black and Native people to have an honest reckoning over what we’ve inherited,” Lowery added. Both groups have been victimized by white supremacy. That inheritance includes centuries of war, segregation and racism due to the legacy of colonial disempowerment.

But also centuries of connection.

Credit: Courtesy Emory University

Credit: Courtesy Emory University

Throughout history African Americans and Native Americans banded together to further their cause for freedom, Lowery noted. Lowery’s Lumbee tribe embraces members who are a mixture of Native, Black and white. “If your kin are Lumbee, then you are Lumbee.” We don’t want to separate ourselves from our kin,” said Lowery.

Harvard historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. has written extensively about Black Americans who assume they have Native American ancestry because of how they look. He notes in his essay “High Cheekbones and Straight Black Hair?” that the number of Black Americans with Native ancestry is very small.

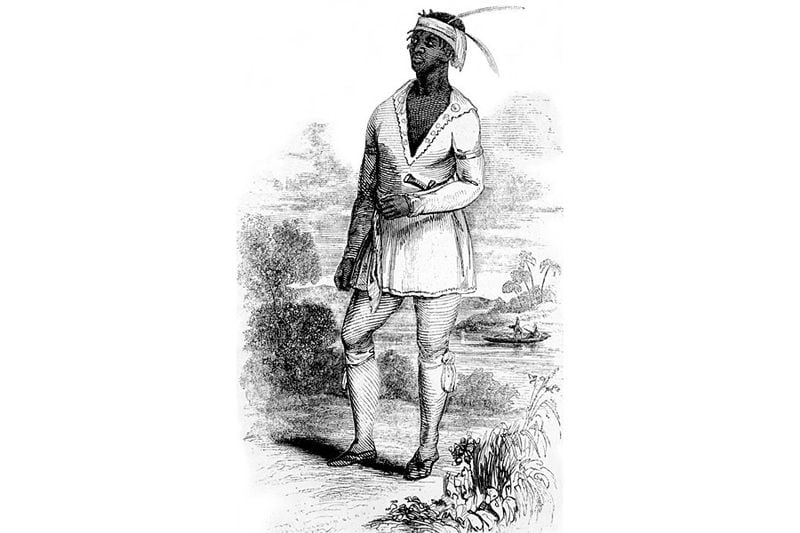

Most Blacks who think they have Native ancestry are really more likely to have white ancestry due to slavery. The exception comes from Blacks who can trace their roots to the five “civilized tribes” that lived in the southeastern United States: Alabama, Georgia, Florida and Mississippi.

Those tribes — the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctow, Creek and Seminoles — were considered civilized because most of them had assimilated into white culture and enslaved Blacks, according to Encyclopedia Brittanica.

Recognition, or verification is one of the most politically touchy areas for Black and Native citizens, they say. Obtaining tribal membership has been a constant battle, for some.

Credit: N. Orr

Credit: N. Orr

The federal government has sought to determine who was “Indian” by blood quantum, or what fraction of “Indian blood” they had.

Today, some tribes still use the U.S. government’s criteria, however most tribes have their own set of requirements for enrollment.

Benefits include taking satisfaction from being a part of a tribe that connects you to ancestors along with state and federal financial benefits.

Marian S. McCormick is the principal chief of the Lower Muscogee Creek Tribe in Whigham, Georgia, near the Florida border. The tribe is recognized by the state but not the federal government. Enrollment for her tribe involves showing unbroken lineage all the way back to a tribal member whose name was on a roll that the government created as far back as 1832. “There was a lot of intermarrying,” she said. But her tribe is welcoming. “We do not discriminate. We do not divide families.”

Kimberly Knight has African and Native American ancestry. Her African ancestry derives from the Ivory Coast and her native roots come from the Haliwa-Saponi and Tuscarora tribes, said Knight, founder of Black Indians NC. But she has declined to pursue enrollment in her tribe, she said. Knight, 41, says she and her family have participated in tribal affairs and ceremonies for years. “I have witnessed people who identify as Afro-Indigenous face discrimination and scrutiny,” said Knight, a clinical social worker.

However, she says she has also seen tribal community acceptance, seen Afro-Indigenous people serve on tribal council, participate in powwow, and represent their tribes on social media.

Credit: Courtesy Kimberly Knight

Credit: Courtesy Kimberly Knight

Knight is co-producer of a documentary, “Duality: A Collection of Afro-Indigenous Perspectives.” The documentary will be released in late September at a symposium on Afro-Indigenous life at North Carolina A&T University.

Both Lowery and Knight say they see hope in the younger Black and Native people to help unify Native Americans and Afro-Indigenous communities and to advocate for social justice and truth in history.

“As an older millennial, I hope generations after me see that we are more alike than we are different. That our collective unity can make social change because it has before,” Knight said.

Both Lonewolf and Knight stress that being Afro-Indigenous does not mean you do not honor your Black ancestry. “One of the most beautiful things about me is I am a Black woman. I honor both of my ancestors and the hardships they faced so I could be here with the accomplishments I have. I don’t take that lightly at all, " said Knight.

Credit: Courtesy Yonasda Lonewolf

Credit: Courtesy Yonasda Lonewolf

Lonewolf says she sees her mission is to be an advocate to bring the two groups together. “We have more in common than we have dividing us,” she said. “I am a symbol of the oppression that both groups – Black and Native – want to be liberated from.”

She credits her late mother, activist Wauneta Lonewolf, with keeping her connected to both cultures. “To see tribes like mine, who historically did not want to, but are now beginning to embrace their mixed children is a beautiful thing,” said Lonewolf. “But we have a long way to go.”

This year, the AJC’s Black History Month series will focus on the role of resistance to forms of oppression in the Black community. In addition to the traditional stories that we do on African American pioneers, these pieces will run in our Living and A sections every day this month. You can also go to ajc.com/black-history-month for more subscriber exclusives on the African American people, places and organizations that have changed the world.