A Homegoing to Remember

Willie Watkins honors the dead with funerals that celebrate Black lives with dignity and flourish.

Julian Reeder’s family was hard to miss amid the sea of black-clad mourners at Riverdale’s Fountain of Faith Missionary Baptist Church one Friday in January. They were dressed in white, matching the luminous suit worn by their beloved in the casket.

The family chose white because it was a color the 52-year-old grandfather of nine enjoyed wearing and because it gave an uplifting feeling to an otherwise gloomy day, says Tova Reeder, Julian’s sister. “We wanted it to be more like a celebration.”

Despite sorrowful, solemn and sometimes tragic circumstances, Black funerals are often marked by a spirit of celebration. A homegoing, as the Black Christian tradition is called, commemorates the return of the deceased to the Lord.

“The Bible teaches us to rejoice in the victory, because you’ve made it over,” says funeral home owner Willie Watkins. This joy is conveyed through careful artistry, whether in a mourner’s choice of clothes, a gospel singer’s soulful voice or a funeral home’s service.

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

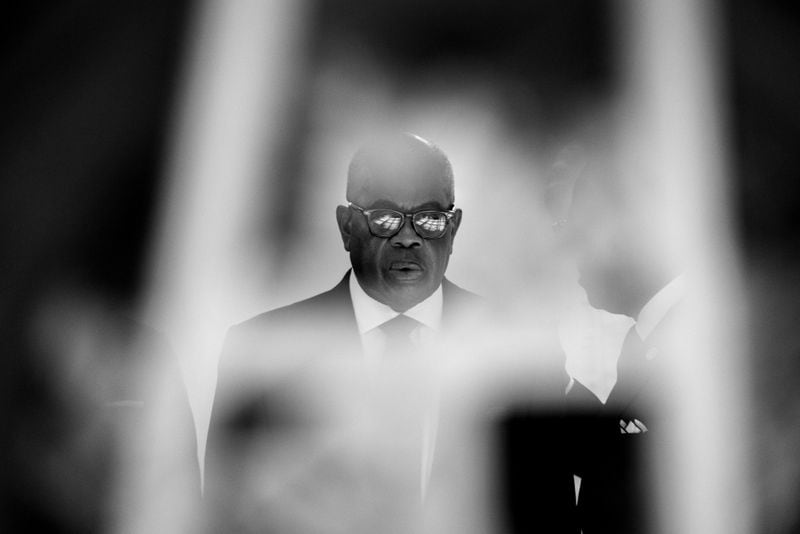

Watkins, 74, is one of Atlanta’s — and the nation’s — most esteemed undertakers. His funeral home has overseen services for everyone from civil rights icons Coretta Scott King and John Lewis to rapper Shawty Lo. But the bulk of his work is for everyday families like the Reeders, who come for the business’ reputation and the special experiences it offers families. Options include crowning ceremonies, dove releases, and transporting caskets in a horse-drawn carriage.

As a boy, Watkins was fascinated by the funerals he attended with his grandmother in Scottsdale. When he was 13, he got a job at Herschel Thornton Mortuary in Atlanta and by 16 he was directing services. In 1978, he bought a spacious, old home in Atlanta’s West End, which became the flagship Willie A. Watkins Funeral Home. Throughout the metro area there are now five locations, which he runs with the help of his family.

“Performance” is the word that best describes the distinctiveness of a homegoing, says Karla Holloway, professor emeritus of English, law and African American studies at Duke University. Black Americans historically were not afforded respect and dignity in American life, but they could counteract that through elaborate funeral rituals.

“Zora Neale Hurston said that Black folk have an urge to adorn,” Holloway says. “The more adornment we can give to the ceremony, the more memorable it is.”

Willie Watkins Funeral Home’s services are certainly memorable. From high-stepping funeral attendants to trotting white horses, the business is known for its for ornate and sometimes extravagant pageantry. It all makes for a sight to behold — a representation as much of vivid life as of death.

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

Credit: arvin.temkar@ajc.com

How we got the story

Staff photographer Arvin Temkar joined The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 2022. Temkar spent three months behind the scenes at Willie Watkins’ Funeral Home, attending services, following employees on their daily duties and talking to bereaved families, to capture some of the artistry and soul that goes into a homegoing.

![Funeral attendants Justin Mayes (left) and Preston Hall watch the service of Julian Reeder. Their top hats are an element of a Willie Watkins “signature” service that families can order to add another level of formality to a homegoing. “I wanted to do something to honor [Julian] in the most high way that we could,” says Tova Reeder.](https://www.ajc.com/resizer/bvuA4YBIXxm5QclWeMeiteE_3Fo=/800x0/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/IDTQZJHGWIMCWPWZ7WKFPIL53Y.jpg)