A year after they were introduced as a symbol for the Women’s March, those outrageous pink hats, to my dismay, were back in the news last week.

I had hoped I’d seen the last of them, but just as sure as seconds turn to minutes, annual anniversaries come and wouldn’t you know this year marked the first anniversary of both the march and President Donald Trump’s inauguration and, well, there the hat was once again.

Photos and television footage showed women happily sporting the pink “pussyhat” symbol, and up pops the controversy surrounding them. Again.

Jayna Zweiman, co-creator of the Pussyhat Project, lists inclusivity, compassion and creativity as the project’s core principles. She has been quoted acknowledging that some feel “the pink color of the hat excludes people of color from the project. Some feel that the hat is a literal symbol of female anatomy, promoting trans-exclusionary radical feminism.”

Zweiman suggests that indeed the outcry about the hats grew so loud that Women’s March organizers even considered leaving them out of this year’s demonstration.

RELATED | When the president says it, does that mean it’s not unprintable?

From its very beginning, the symbol has left me feeling uneasy.

Not because of its pink color as some women of color have objected and not because not all women have vulvas as the transgender community has argued.

It’s the very word itself.

Use of it is no different than, say, the vulgar slurs some people use to refer to black people or women.

You can argue it takes away the power of the word as much as you want. I say your windpipes are full of air.

I thought I might be the only woman feeling some kinda way about the word, but Deborah Cohan agrees.

“I bristle at this sort of thing as well,” said Cohan, a professor of sociology at the University of South Carolina-Beaufort. “I see it as part of the same continuum you do. Jewish women referring to themselves as JAPs, blacks using the n-word, women calling each other bitches. It’s part of internalized oppression. This happens when people from historically marginalized and oppressed groups take the hateful words used against them and use them with and against people in their same group.”

RELATED | Rally goal: turn Women's March into movement aimed at election

“Some see this as a sort of victory, triumph and celebration because it is reclaiming and repositioning what has been leveled and used against them as well as a way to rechannel legitimate rage back at those who have dominated and exerted power and control.”

Although Sonya Huber, associate professor of English at Fairfield University and founder of the Disability March and Disability March 2, felt “a little shocked” when she first heard the term, she doesn’t anymore.

For Huber, pussyhat is about a reclaiming of the language, a way of refusing to be dismissed or violated by the president’s crude misogyny, in the same way that women have tried to reclaim “bitch” and other terms and infuse them with positive associations that give them some agency.

“I believe women may be searching for a new stance from which to fight against the degrading sexism that came up in the 2016 presidential campaign,” Huber said. “To me, it isn’t an anatomical reference. It’s become a larger way to claim everything for ourselves that has been rudely taken advantage of by men who would exploit us. The object of the hat itself contains an element of humor, a kind of wink and a play on the innocence of a kitten, but with claws. The double-entendre is a reinvention offered through homemade and handmade objects, a grass-roots response that refuses to back down in the face of what it meant to intimidate us.”

RELATED |Why two Atlanta women will join their first protest march

Cohan agreed that some of this is done in a playful and humorous way and for people marching to come together and use this as a way to reduce their own pain and suffering.

“There appears to be a motivation, fed by social media, selfie culture, etc., to demand to be taken seriously while at the same time trying to appear playful and humorous,” she said. “Time will tell what will truly be the most effective mobilizing strategy. It might be that we need new language and new symbols for resistance to create new ways of being. As I see it, this will necessarily involve a powerful combination of righteous rage and compassion.”

Cohan said she tends to favor language that carries some greater sense of self-respect. A lot of us do.

Fashion and activism has a long and hearty history, said Amanda Hallay, a professor of fashion merchandising at LIM College and host of the popular YouTube channel The Ultimate Fashion History.

“Although the form of the hat resembles kitten’s ears, it takes no imagination to realize the true origin and intent of the name,” she said. “But a knitted wool hat (in pink, no less) that resembles kitten’s ears is hardly empowering, and seems weirdly antithetical to the serious issues at hand.”

Still, Hallay said it didn’t surprise her that the current women’s movement found its sartorial element. That’s nothing new.

“Think of Les Sans Culottes of the French Revolution, with their striped pants and Phrygian caps, or even the cowboy or leatherwear at one time favored by the gay rights movement,” she said. “I just personally wish that, this time, the garment in play was a little less ‘Hear Me Purr’ and a lot more ‘Hear Me Roar.’”

Me, too.

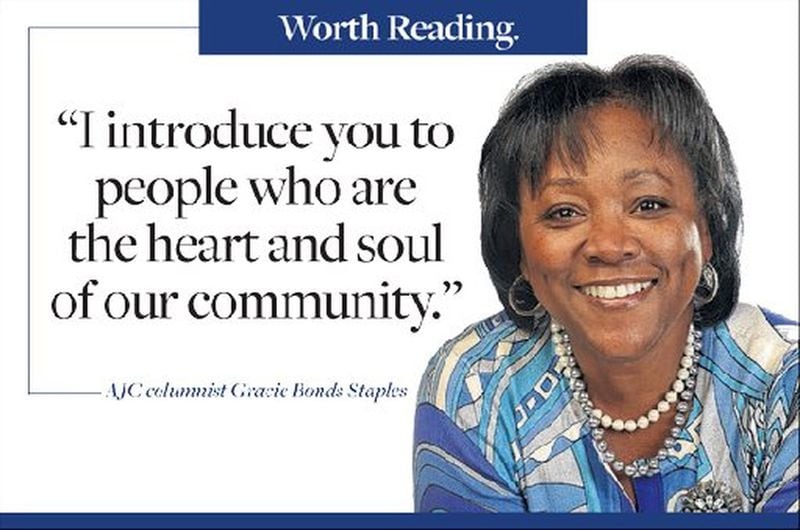

About the Author