In 1942, a secret group of teenage boys produced an underground magazine while imprisoned inside the walls of the Terezin Ghetto, a Czechoslovakian show camp designed by the Nazis to hide their plans of mass extermination.

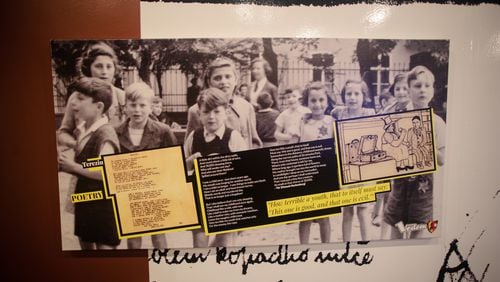

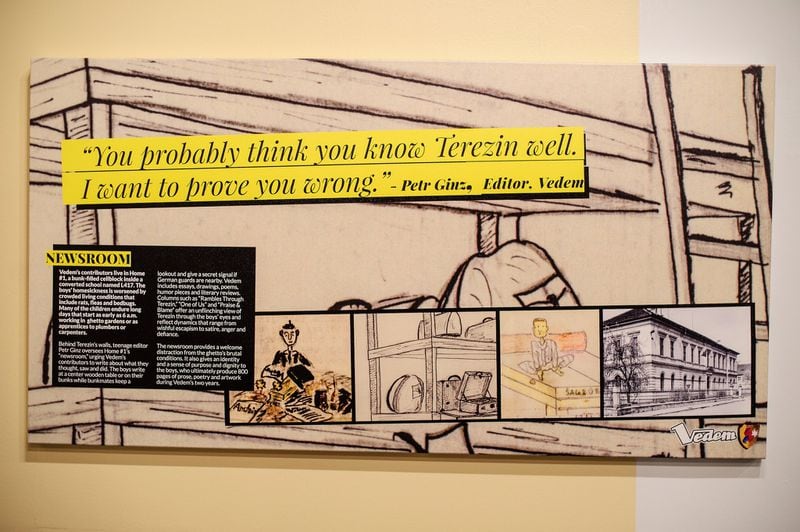

Living in what was previously a classroom, the boys found a typewriter and started documenting the daily life and struggles inside the 18th-century walled fortress about 40 miles north of Prague. The publication also revealed the inner thoughts of teenagers through poetry, illustrations, even jokes.

The title of the magazine is at the top in black ink and large — Vedem, which means “in the lead” in Czech.

A powerful new exhibit exploring the magazine, titled "Vedem Underground: The Secret Magazine of the Terezin Ghetto (1942-1944)," opened this week at the Breman Museum in Atlanta. The exhibit will be on display through March 10.

The exhibit premiered about two years ago at the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Museum of Tolerance in Los Angeles, and since then, it has traveled to other cities including Houston, Portland, Ore., and Austin, Texas. This marks the first time the exhibit comes to the Southeast. The exhibit, which features reproductions of Vedem, is an art installation that deconstructs the literary work of the longest-running underground magazine in a Nazi camp.

Named one of Smithsonian magazine’s 10 “Don’t Miss” new exhibits for winter 2017, this exhibit was produced and curated by Rina Taraseiskey, granddaughter of Holocaust survivors. She is also the executive director of the Vedem Foundation, and working on producing a documentary about Vedem. For the exhibit, she also worked with Dallas-based writer and journalist Danny King, who is producing and co-writing the companion book, and art director Michael Murphy.

The first 30 issues were created using the typewriter. After the ribbon went dry, 53 issues were produced by hand. The weekly issues were accompanied by cartoons and illustrations — including cartoons about sick prisoners and a cartoon of a guard staring at a boy. Other art work featured the boys’ hometown of Prague — landscapes, cafes, a family dog. Here is an excerpt from a poem written by one of the contributors, Hanus Hachenburg.

What good to mankind is the beauty of science?

What good is the beauty of pretty girls?

What good is a world when there are no rights?

What good is the sun when there is no day?

One of the most well-known writers was the publication's editor-in-chief, Petr Ginz, who was a wise-beyond-his-years Czech teen.

As a young child, Petr fell in love with books, and was a prodigy, writing five novels before the age of 12. On Oct. 24, 1942, Petr, only 14 years old, was sent to Terezin (also known by its German name Theresienstadt) for having a Jewish father.

Shortly after his arrival, Petr and other boys started publishing the underground magazine Vedem, which consisted of over 800 pages over two years. Petr occasionally paid for articles from other contributors using food that his non-Jewish mother sent him in packages. Only one copy of each paper was made, and there would be secret Friday evening readings in their bunkroom.

The editions were later buried in a metal box. They were dug up by a surviving Vedem writer after the ghetto was liberated.

“The darkened depths of the Kavalir Barracks stink of latrines and are filled with physical and mental muck,” wrote Petr. “The only worry is to eat enough, get some sleep, and what more? An intellectual life? Can anything else exist besides the mere animal instinct to satisfy bodily needs? Yet, it is possible. Creativity does not perish in the mire. Even here, it sprouts and blossoms like the blind artist, Berthold Ordner, a star shining in the dark.”

MORE: Atlanta group plants daffodils downtown to spread Holocaust awareness

Of the 15,000 children who passed through the fortress's gates at Terezin, only about 150 survived. Of the 40 boys who contributed to Vedem, nine survived, according to Taraseiskey. On Sept. 28, 1944, Petr was sent on a transport and ultimately to his death at an Auschwitz gas chamber. Hanus was also sent on a transport to Auschwitz. Some of the surviving children who contributed to Vedem eventually immigrated to the United States.

King, one of the co-creators of the exhibit, said even though the boys wrote about a solemn subject matter, they were, after all, teenage boys, and they sprinkled humor throughout the publication, “to help keep their minds off being in prison.”

“The range of subject matter was stunning. On the light side, there was everything from bathroom humor to girl crushes to sarcastic references to the guards,” said King. “And then there would also be something as somber as working in the crematorium.”

King said the curators of the exhibit wanted to give the exhibit a bold punk rock ethos to help make it visually contemporary and accessible to young people. It’s recommended for visitors who are at least 10 years old.

“These boys were not victims,” said King. “They were incredibly courageous and sought the truth at great risk. … We are hoping viewers, especially young viewers, will see them as examples to follow.”

MORE: MJCCA's 27th annual Book Festival: how it all comes together

The publication had a logo of sorts — a shield with what looks to be a rocket shooting into a book.

According to interviews with some of the survivors, King said, the shields “stood for pursuing knowledge and shooting for the stars.”

The boys also penned a manifesto that is showcased at the exhibit in capital letters, highlighted in bright yellow. It includes the following:

We shall not allow our hearts to be hardened by hatred and anger, but today and forever, our highest aim shall be love for our fellow men, and contempt for racial, religious and nationalistic strife.

EVENT PREVIEW

“Vedem Underground: The Secret Magazine of the Terezin Ghetto (1942-1944)”

Through March 10. 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Sundays-Thursdays; 10 a.m.-4 p.m. Fridays. Closed on Saturdays. Please note: The museum is closed on most Jewish and federal holidays. Check the museum calendar for specific dates. $4-$12; free for children under 3 and members. Breman Museum, 1440 Spring St. NW., Atlanta. 678-222-3700, thebreman.org.

About the Author