This story is one in a series of Black History Month stories that explores the role of resistance to oppression in the Black community.

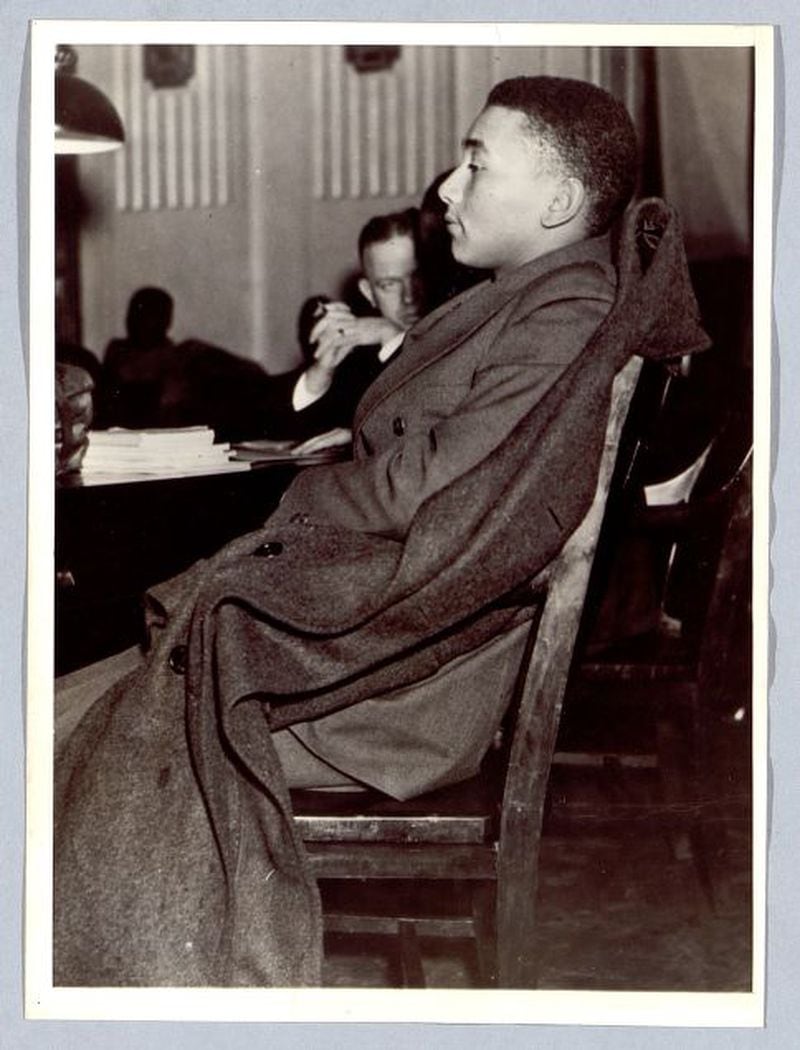

In January 1933, Angelo Herndon, a 19-year-old Black worker accused of “attempting to overthrow the lawfully and constituted authority of the state of Georgia,” stood in front of a packed courtroom and delivered a social commentary that is eerily relatable today.

“The present system under which we are living today is on the verge of collapse; it has developed to its highest point and now it is beginning to shake,” said Herndon.

Almost a century later, when more than 900 people have been charged in the Jan. 6 insurrection at the nation’s capitol, Herndon’s words still ring true. The systems we are living under have definitely begun to shake. In both cases, the defendants are charged under Civil War era insurrection laws, but that is where the similarities end.

Herndon, an avowed communist, had organized roughly 1,000 unemployed Black and white workers to march at the Fulton County Courthouse to demand financial assistance after the state dropped 23,000 families from the relief rolls during the Depression. Their peaceful protest was successful, but Herndon was later arrested and jailed. He was certain the all-white jury would sentence him to death.

Herndon would endure a five-year journey to justice as his case wound through Georgia Superior Court to the U.S. Supreme Court. This was international news, but even though Herndon prevailed, his story faded with time, a significant, if largely ignored, piece of American history.

Credit: Associatd Pr

Credit: Associatd Pr

“The Herndon case shows how the system of white supremacy in the South tried to suppress both Black and interracial activities to challenge the economic and political status quo. Legally, it gave rise to the revitalization and application of the clear and present danger test for laws restricting free speech,” said Charles Martin, emeritus professor of history at University of Texas at El Paso and author of one of the few books written about Herndon.

During his time in prison, Herndon wrote his own story in an autobiography titled “Let Me Live” published by Random House in 1937 and reissued by the University of Michigan Press in 2007. He described his upbringing in a religious household in Wyoming, Ohio, and the death of his father, a coal miner, when Herndon was 9. When he left home at 13, Herndon went to work for coal mines in Kentucky and Alabama, where he soon found his voice as an organizer.

The Great Depression was setting in and Herndon saw workers losing jobs, losing pay and losing hope. Social movements including socialism, populism and radicalism had already been moving through the South, said Robin D. G. Kelley, professor of American history at the University of California Los Angeles, who has written extensively about social movements and Black radical thought. When the Communist party took off in the South in the 1930s, its core membership was Black people.

For Black Southerners, the idea that the means by which people live should be owned or run by the state or by the people was not foreign. Their brand of communism, often practiced beyond the eyes of the national leadership, infused elements of Christianity (meetings began with prayer) along with traditional teachings of equality for all.

“Black people transformed this thing seen as sinister. They made it their own,” Kelley said. “They were fighting for basic civil rights and they were fighting fascism.”

Atlanta was a primary center in the nation for the American Fascist Order of the Black Shirts, composed of 21,000 white jobless workers seduced by the rally cry “America for Americans!” Members were promised jobs that never materialized in return for violence against Black workers, wrote Herndon.

But disillusioned Black Shirts would soon decamp for the Communist party, and after repeated jail stints in Birmingham for organizing activities, Herndon moved on to Atlanta just in time to harness the growing frustrations of Black and white workers. He kept a low profile until the summer when county and state financial relief stations closed, leaving hundreds of out-of-work sharecroppers and their families starving.

The county agreed to hear the grievances of the people, and party members rushed to inform others that they should come to the courthouse for a demonstration. Herndon arrived early that morning, worried that none of the workers would show, but slowly the square began to fill until a thousand workers — half of them white, half of them Black, both men and women, some with children — stood shoulder to shoulder and demanded relief. Within 24 hours, county commissioners coughed up $6,000.

The march had been peaceful, but county officials were shaken. If this Black man from the North could rally a thousand Black and white people to successfully demand unemployment assistance, what else could he, or the Communist party, do?

“Interracial organizing was considered dangerous,” Kelley said. White people felt they had one of two choices: view Black people as equals and allies and afford them the same wages and benefits or indulge white supremacy above all else, which dictated that Black people needed to be oppressed, killed or deported.

Herndon was arrested at the city post office and held in jail before he was indicted for attempting to overthrow the state government. The alleged insurrection was dated July 16, when Herndon was already behind bars.

He was charged under a dusty statute from 1883 initially intended to squash slave rebellions but later revised to apply to any insurrection against the state. Anyone convicted of circulating insurrectionist materials, attempting insurrection or inciting others to do so could receive five to 20 years in prison or face the death penalty. Only two people were ever convicted under this statute, a Black preacher in 1868 and Herndon.

Herndon’s case was devoid of the sexual dynamics that usually accompanied criminalization of Black men such as the Scottsboro Nine, the Black males ages 13 to 20 accused in Alabama of raping two white women in 1931. Testimony in Herndon’s case centered on Communist ideals, which Southern segregationists cast as a tool for racial equality that would disrupt societal order with interracial marriage.

With little evidence of insurrection, state prosecutors hung their case on Herndon’s engagement with the Communist party. The International Labor Defense (ILD) contracted Atlanta attorneys Benjamin J. Davis Jr. and John H. Geer to represent Herndon as the state built its case against communism, the only charge recorded on his case file.

Officials raided Herndon’s home and produced Communist party materials including books, pamphlets, and receipt pads for party membership. In court, professors from Emory University testified that the materials could be obtained by any library patron.

After a short trial in Fulton County Superior Court, Herndon was found guilty and sentenced to 18 to 20 years on the chain gang. His attorneys appealed but Georgia Supreme Court upheld the conviction in 1934 and a year later, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 6-3 against Herndon and sent the case back to lower courts.

A few months later, the U.S. Supreme Court denied a re-hearing, but Herndon caught a break when Judge Hugh Mason Dorsey, a former governor, took the bench of Georgia’s Appeals Court and found the outdated insurrection laws were too vague. The state Supreme Court upheld the original conviction, but when Herndon’s case was sent back to U.S. Supreme Court, justices overruled the Georgia Court in a vote of 5 to 4.

Credit: Associatd Pr

Credit: Associatd Pr

The case would prove the final blow to Georgia’s insurrection statute, but it also changed the landscape for white liberals who had previously been dismissive of civil liberties for Black Americans. “If you were a white liberal in the South, you were a segregationist, but this case forced a lot of people off the fence,” Kelley said. “Suddenly you get academics and progressives coming to testify, saying we have gone too far, you cannot execute someone for holding literature that anyone can get in the library.”

Now a free man, Herndon married Joyce Chellis in 1938, and though he had resolved to return to Georgia, he never did. He moved back to the Midwest and worked as a salesman before his death in 1997.

For a time after his release, he worked in various capacities for the Communist party before parting ways, as did many Southern Black people during the Cold War when party leaders thought it best to downplay allegiance to Black equality in America.

“The Cold War erasure has affected our ability right now in 2023 to understand how important the Communist party was in the longer trajectory of the civil rights movement,” Kelley said.

Young Black people, moved by Herndon’s case would form the Southern Negro Youth Congress, the predecessor of the youth movement that sparked the civil rights movement.

Black communists had considered themselves part of an international movement for justice, Kelley said. They recognized intersectionality before the term was ever used, embracing the Black poor, the Black working-class and Black women.

“The party built leaders out of people who were told they could not lead,” Kelley said. “What the Communist party represented was not just anger at injustice but an analysis of how society works.”

They were small in number, but Southern communists had outsized ideals of what American society could and should be, and Herndon was a leader among them.

For more subscriber exclusives on the African American people, places and organizations that have changed the world, go to ajc.com/black-history-month.

![[Cropped for promo]](https://www.ajc.com/resizer/jBdr8krVIzWTzzSE9YiR2AqV_1s=/500x282/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/V2HRMZBWP5CRJCLEYMR5Z5D4TI.jpg)