On Nov. 30, 1985, Belton Lamont Platt got himself into a shootout. He shouldn't have been there. No one involved should have been there. Thankfully no one was killed, which was common enough in those public-housing projects, in that part of Charlotte, N.C. In "Money Rock: A Family's Story of Cocaine, Race, and Ambition in the New South," author Pam Kelley tries to figure out what, why and how it happened. But none of it should have happened at all.

By “none of it,” Kelley doesn’t just mean this particular flash of violence, in that particular neighborhood of Piedmont Courts, or those particular African-American kids (Platt was 23 at the time). The veteran journalist, a longtime reporter for the Charlotte Observer, instead chooses to use the incident, and Platt’s family life, as a lens through which the reader views systemic racism and urban gentrification in the post-1960s South.

Kelley digs deep into the archive of her city’s history to trace how Platt — nicknamed Money Rock both for his drug-dealing prowess and his general swagger — got to that point, and where he went after. Platt spent more than 20 years in prison and found redemption as an evangelical preacher.

Charlotte, like Atlanta, modeled itself as a “city too busy to hate.” During the 1960s and 1970s, it desegregated its institutions (busing and schools in particular) with relatively little violence, through a multiracial coalition of civic activity. It avoided the riots of Newark and Watts, the bombings of Birmingham, the ugliness of Jackson’s sit-ins, and the vicious segregation protests in Little Rock and Oxford.

Through diligent shoe-leather research, synthesis of academic monographs and her own interviews with Platt and his family, Kelley paints a different, more nuanced and disturbing portrait of the city. Charlotte’s government was just as guilty of redlining and under-funding public housing as any other city council in America, just as prone to disproportionate arrests and police brutality against its black citizens, just as likely to raze its African-American neighborhoods and commercial districts. It just hid it better, buttressing it under pro-business interests and good marketing.

All of that left black Charlotte in trouble during the ’80s and ’90s, a collapse that it still hasn’t quite escaped in 2018. In Kelley’s work, we see the New South city’s changes through the eyes of its most impoverished, rather than through those trained to see it at its most robust and progressive. Like David Simon and Edward Burns’ “The Corner: A Year in the Life of an Inner-City Neighborhood” (1997) and Sudhir Venkatesh’s “Gang Leader for a Day: A Rogue Sociologist Takes to the Streets” (2008), “Money Rock” is an ambitious and sometimes overreaching mix of journalism, pop sociology and op-ed commentary.

Kelley’s voice is ever-present, but her presence in the narrative is notably, refreshingly absent. Beyond the preface, in which she details how she came to follow Platt’s life, Kelley keeps herself out of the story. The use of “I” doesn’t come up much; she respects the contours of the people she’s chronicling too much to intrude, to centralize herself in the tale. When she does, again in the preface, she’s setting up the racial divides and class issues that dominate “Money Rock.”

But Platt’s presence also is missing. The chapters alternate, more or less, between closeups of Money Rock’s life and panoramic views of Charlotte (or even America) during the same time. Even in chapters purportedly concentrating on Platt, he’s gone for long periods as Kelley digresses and pontificates on larger themes. She’s vivid and almost cinematic in her scope, but her protagonist is often a ghost in his own story.

While reading “Money Rock,” I kept flashing on the 2016 ESPN documentary, “O.J.: Made in America.” Ezra Edelman’s film and Pam Kelley’s book both focus on troubled black men whose lives let us see American cities with complex histories regarding race and crime. Both the movie and the book make periodic digressions into sociology and politics, systemic racism, contemporary news reports and backstories. Both are urban sprawls, in other words.

“O.J.: Made in America” is more than seven hours long but somehow too short and altogether riveting. “Money Rock” is standard size, less than 300 pages, but feels padded. Maybe that’s because “The Juice” looms larger in American culture than a two-bit drug dealer who found God in prison. O.J. was everywhere for decades — in football games, Hertz commercials, silly movies, and, oh yeah, a yearlong murder trial. But I suspect it’s also because Kelley can’t quite make Platt and his family either as singular or as archetypal as they need to be to serve as surrogates for the black urban South.

All the same, "Money Rock" doesn't condescend to its protagonists, and Kelley seems genuinely, passionately interested in exposing the urban South's ills. Platt is made in America, just like Orenthal James Simpson. If he doesn't seem quite made of America, if his failures don't seem quite coupled neatly with America's, at least Kelley seems interested in closing the gap in our understanding.

NONFICTION

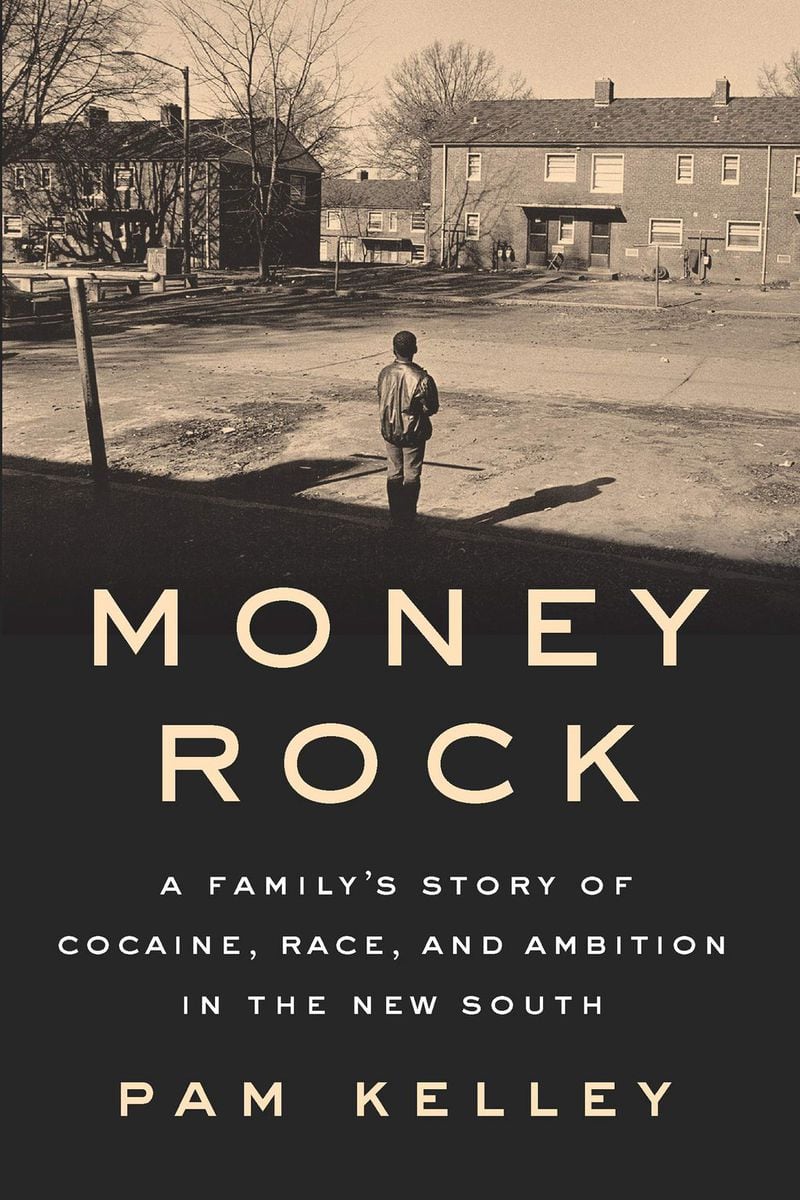

‘Money Rock: A Family’s Story of Cocaine, Race, and Ambition in the New South’

by Pam Kelley

The New Press

282 pages, $26.99