The U.S. Supreme Court has made it clear that prison inmates must receive some form of medical care. After all, what other options do they have?

Far less clear is how good that care has to be.

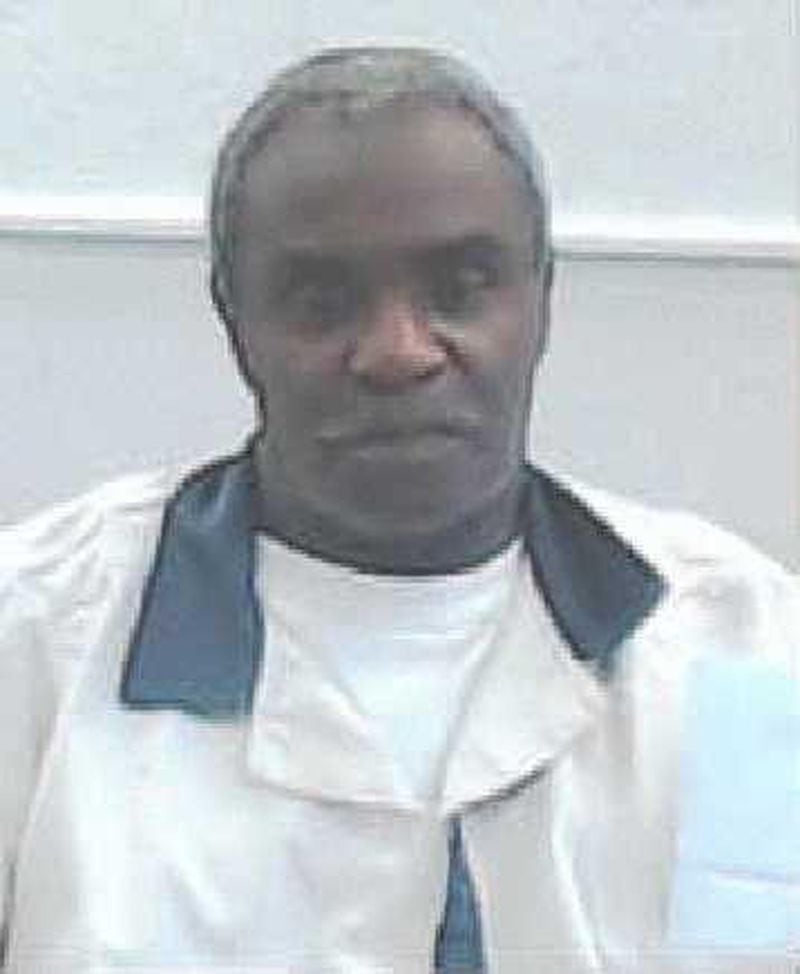

The issue, open to discussion for decades, is front and center in the case of Michael Tarver, the Georgia inmate who lost his left leg when a small scrape became severely infected at Macon State Prison.

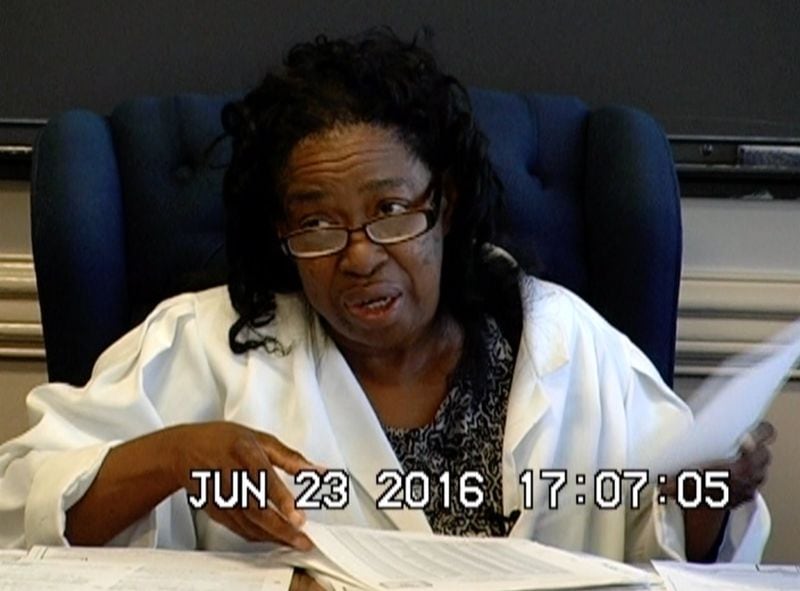

Tarver is suing the prison's medical director, Dr. Chiquita Fye, claiming she failed to deal properly with his wound as it gradually worsened. As a diabetic with a history of circulation problems, the 55-year-old inmate was vulnerable to infection.

Credit: Lois Norder

Credit: Lois Norder

But the question to be decided isn’t whether Fye, an Emory-trained physician who has worked in the prison system for more than a decade, was negligent in dealing with the inmate’s condition. It’s whether she was deliberately indifferent to it, a far tougher thing to prove than medical malpractice.

"It's a very stringent standard, especially in the 11th Circuit," said David Schoen, an Alabama-based attorney, referring to the federal appeals court that serves Georgia, Alabama and Florida.

The Supreme Court, ruling 41 years ago in the case of Estelle v. Gamble, held that prison inmates have a right to adequate healthcare. Deliberate indifference to inmates' medical needs violates the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits governments from imposing cruel and unusual punishment, the court determined.

Since that ruling, a lower court decision has determined that deliberate indifference requires proving that a caregiver knew of a risk to an inmate’s health and still disregarded it.

That standard now guides all federal lawsuits alleging prison medical mistreatment, and it’s the one that will be at the heart of Tarver’s case, scheduled for trial the last week in September in Macon.

People who are incarcerated typically are unable to sue for medical malpractice because they can't obtain the affidavits from medical experts required at filing.

The upshot is an "uphill battle" for inmates, particularly those who don't have legal representation, says Joel H. Thompson, staff attorney with the Prisoners' Legal Services in Boston.

“For too many prisoners, the Eighth Amendment does not ensure adequate medical care,” he wrote in the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review. “Prison medical providers may be aware of their constitutional obligations, but they are also aware of the conflicting need to limit costs.”

Credit: Carrie Teegardin

Credit: Carrie Teegardin

Tarver, who is serving a sentence of life without parole for the 1994 murder of a Columbus convenience store clerk, initially filed his case “pro se” -- without legal representation -- but was able to hire an attorney, Mike Brown of Augusta, who has since guided the case through discovery.

Brown has obtained depositions from five former Macon State Prison healthcare workers who say Fye ignored signs of the worsening infection, including the smell of rotting flesh and the presence of black tissue inside the wound. He also has enlisted the aid of one of the nation’s leading wound care experts, Dr. John Macdonald, who has testified that Fye’s treatment was “so far below the standards of proper medical care … as to evidence a conscious disregard.”

Based on that evidence, U.S. Magistrate Judge Stephen Hyles denied Fyes' motion for summary judgment, ruling that “there is a genuine material issue of fact regarding whether Dr. Fye was deliberately indifferent” to Tarver’s needs. U.S. District Judge Marc T. Treadwell affirmed Hyles' decision.

Read more about the case by clicking here: http://bit.ly/2ixad9O

Credit: Lois Norder

Credit: Lois Norder

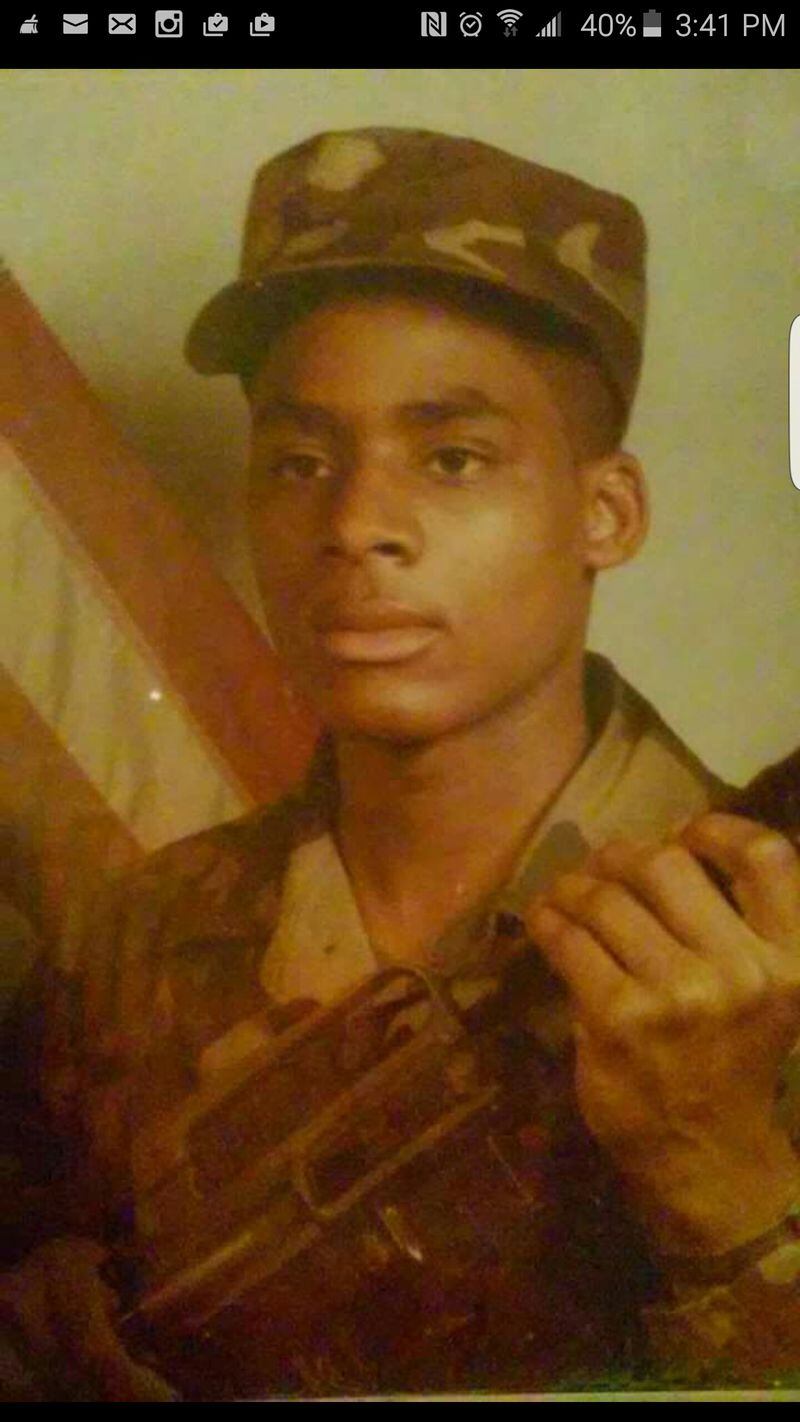

Schoen, whose office is in Montgomery, Ala., has been dealing with such cases for more than 30 years and currently is representing the family of Phillip David Anderson, who died from a perforated ulcer while in the Tuscaloosa County jail in 2015. The federal lawsuit says jail staff stood by as Anderson, a 49-year-old Army veteran who was jailed for missing a child support hearing, screamed and collapsed in pain.

Schoen says there’s no doubt that Anderson deserved better care, but proving that jail personnel acted with deliberate indifference is another matter, one that will require years and possibly a trial.

“These rules are very complicated,” he said. “That’s why the `pro se’ cases get thrown out. That’s why most lawyers don’t want to touch them. They’re hard to win.”