University of Georgia professor Peter Smagorinsky enjoys the PBS mega-hit "Downton Abbey," but says a current plot line about a character becoming a teacher romanticizes the profession and minimizes the struggles to become excellent at it.

By Peter Smagorinsky

As the final season of "Downton Abbey" winds down, the manor faces the dwindling of the service staff as old estates face new social and economic realities. The eternally snake-bitten Mr. Molesley finally finds satisfaction, appointed as a teacher in the Downton School. But his first day in the classroom is a disaster.

Back in the Abbey, he is consoled by Mrs. Baxter, who suggests he share his experiences as a man of humble origins with his students. On Day 2, after acknowledging he has come to the classroom from a lifetime of service and is not a well-bred intellectual, the students respond they, too, have known lives of scarcity, and quickly resonate with him on a personal level.

Within minutes, he has their rapt attention and proceeds with a lesson that leaves his students “spellbound,” according to Daisy. He is, she cries, a “natural” teacher.

Credit: Maureen Downey

Credit: Maureen Downey

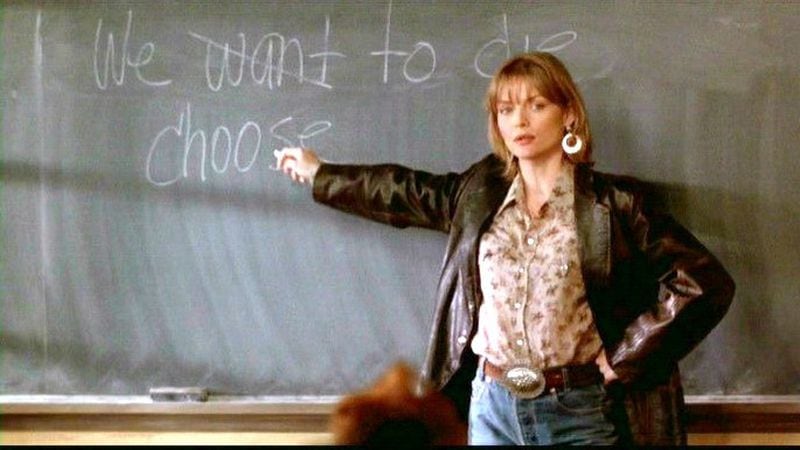

I'm a fan of "Downton Abbey," but this storyline bothers me. It is part of a long line of cultural narratives in which simple changes by teachers can rapidly convert students from brutish swine to dedicated scholars: Michelle Pfeiffer's appearance in a leather jacket in Dangerous Minds, Hilary Swank's acknowledgement of a mistake in Freedom Writers, and many more classroom myths.

Credit: Maureen Downey

Credit: Maureen Downey

In my most recent interview with a teacher whose career I have followed for the last seven years, she spoke of the exhaustion she has always felt as a teacher from being compared to these cultural narratives.

Failing to live up to those images has always left her feeling inadequate. Why doesn’t the leather jacket work for me? she wonders.

The prevalence of such narratives has become rooted in many teachers’ conceptions of their own value, even when they know Hollywood provides miraculous scripts of success that aren’t available in the teeming world of the real school classroom.

It also seems to suggest that scripts can change how teaching and learning unfold. Much instruction these days is heavily scripted so there is great alignment across teaching and assessment.

Now, it's important for teaching to be aligned with assessment, don't get me wrong. But assessments are now written by people far removed from the classroom, and their scorers come from such sources as Craigslist ads.

And yet, simple fixes dominate the national narrative on how to address challenges facing schools. These challenges themselves are usually grossly exaggerated in order to make the solutions more attractive, whether it's charter schools, vouchers, accountability testing, or other romanticized solution to problems that may or may not even exist.

This belief in the simple solution is now well-ingrained in the public mind, to the detriment of the teachers who daily tackle the real challenges facing schools, suggesting all we need to make hungry, malnourished children gritty enough to become eager learners is a really cool teacher.

Education does face problems. Among them is the myth that educational problems are easy to fix with a simple solution. That works in Hollywood, but basing policy on fiction is bad policy in Georgia and other states. I just wish the policymakers could recognize that among the major problems facing education is that fiction more than fact provides the basis for the policies that they impose on teachers and students.

About the Author