Matthew Dischinger has taught humanities courses at the University of Alabama, Louisiana State University, and Georgia Institute of Technology. He is a lecturer in the Department of English at Georgia State University.

In this guest column, he makes a case for humanities majors.

By Matthew Dischinger

If you or your college-bound student are trying to decide what to major in this fall, I have some good news about the humanities: it’s not just for baristas anymore.

This particular stereotype is both harmful and, according to recent research on the connection between education and employment, undeserved. Two independent firms researching labor and education, Burning Glass and the Strada Institute, published a study in May that explored the long-term effects of underemployment, or the now all-too-common phenomenon of working in a job for which one is overqualified.

What they found was fascinating. According to the study, one of the most popular clusters of majors—business, marketing, management, and others—is among the riskiest for short and long-term earning potential. The underemployment probability rate for these majors was a whopping 47 percent, leaving roughly 282,000 of the more than 600,000 graduates of the 2016 class underemployed. After five years of underemployment, that number still sits above 183,000 graduates. English, one of the most often-maligned humanities disciplines, left only approximately 16,400 graduates, or 29 percent, underemployed after five years.

To what should we credit these findings? Majoring in the humanities teaches students much more than it typically gets credit for.

Rather than merely exploring obscure texts, humanities courses teach a set of core skills and ideas that sharpen critical thinking. Another study, this one by the Hart Research Associates, found that more than 80 percent of employers look for the very skills that humanities disciplines teach: written and oral communication, critical thinking, and analytical reasoning.

Just as STEM disciplines provide knowledge learned through coursework and practice, effective critical thinking and communication are hard-earned skills learned through repetition.

Contradictory as it may seem, the city of Atlanta’s courtship of Amazon and other tech industry giants makes these skills more important for Atlanta’s graduates, not less. Amazon’s founder, Jeff Bezos, is just one of many tech industry leaders famous for bucking conventional corporate trends by drawing on skills traditionally developed in the humanities.

For instance, Bezos requires Amazon’s employees to write narrative memos ahead of meetings rather than relying upon the standard (and dull) bullet-pointed presentation. According to Bezos, “There is no way to write a six-page, narratively structured memo and not to have clear thinking.” Narrative structuring does not merely dress up an idea, in other words. It improves and sharpens the idea.

Given the state’s relentless pursuit of Amazon, specifically, it can only help that Atlanta’s institutions of higher education all feature excellent and innovative humanities-driven initiatives. Some of the most exciting work at institutions like Georgia Tech and Georgia State, in particular, happens at interdisciplinary centers that show students the value of collaborative problem solving in local communities. Georgia State’s Urban Studies Institute and Georgia Tech’s Office of Serve-Learn-Sustain are two such centers that bring scholars across the disciplines together.

These centers focus their research and teaching on shaping Atlanta’s future with equitability and sustainability in mind. They are two of many interdisciplinary centers at Atlanta institutions proving that the knowledge provided by STEM disciplines is both essential and incomplete.

Humanities work also prepares students for professional lives in what we think of as purely scientific fields, like medicine. While prevailing wisdom might suggest that the best preparation for this work is a singular undergraduate focus on STEM disciplines, a 2017 study by the Association of American Medical Colleges proved that humanities majors had higher medical school acceptance rates in 2016 than those in biomedical sciences, social sciences, and physical sciences.

Medical students and doctors echo the sentiments of professionals in other fields: STEM knowledge helps students understand the body, and humanities skills make them good doctors.

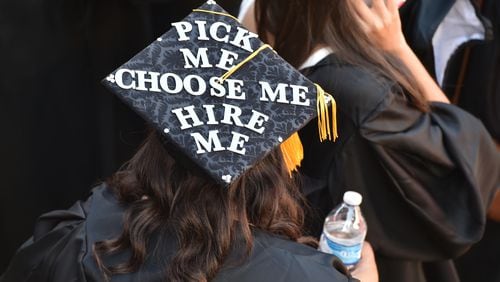

Regardless of how students approach their coursework, finding a good job is not easy. The rhetoric of soft skills versus hard skills, however, leads one to believe that the knowledge provided by a STEM education is wholly responsible for short and long-term career success. What these recent studies point out is that graduates need to be dynamic thinkers and communicators if they want to succeed in an increasingly competitive job market.

Of course, there is so much more that a humanities education offers. Without devaluing these more abstract ideas—such as civic engagement, ethics, and fulfillment—it is clear now more than ever that studying the humanities prepares students for professional success.