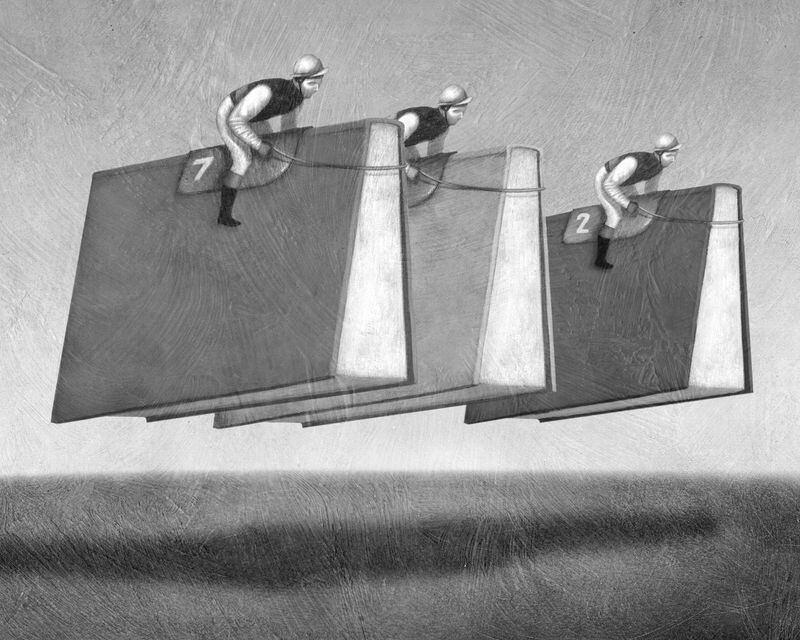

A former business owner turned teacher examines the assumption underpinning much of the current reform movement -- competition is a healthy force that will drive improvement in teaching and learning.

This piece is by Chuck Bennett, a teacher at Chestatee Academy in Hall County.

By Chuck Bennett

Credit: Maureen Downey

Credit: Maureen Downey

I owned and operated a business for 16 years and have been a teacher and coach for the last 13. I’m a believer in market economics and the idea that competition makes for better performance. But my experience as teacher and just plain common sense have proven to me that a competitive business model is not the best solution for every situation.

It is certainly not the best model for education.

If I own shares in Pepsi, then I am pleased whenever Coke stumbles. Their failure is my gain. A competitive model encourages Pepsi to increase market share at the expense of Coke. The market system incentivizes Pepsi to seek any competitive advantage it can over Coke. As a shareholder, I would be furious if Pepsi shared trade secrets with Coke.

The premise behind public education is fundamentally different from the premise behind a business. It is in our society’s interest for all students to succeed because the life of our democracy depends upon having educated citizens, a capable workforce and discerning consumers. Imposing a competitive system on public education works against that basic premise.

For example, with our evaluation system (TKES), I, quite literally, benefit if the teachers in the grades before me fail. If my students come to me with poor test scores and then they get good scores under me, they will have shown tremendous growth. My evaluation will be great!

What then is the incentive for me to collaborate with those teachers, to share ideas, or to do anything other than sabotage them? The same goes for the teacher across the hall, against whom my scores will be compared. On a larger scale, the same goes for the relationship between every other school.

If you say that I should do these things because it is what “is best for the students,” then you accept the basic premise of public education. You cannot create a system that incentivizes competition and then expect me to work against my own self-interest.

On a practical level, I want every student to do well. I benefit from a society with great novelists and great entrepreneurs, great artists and great medical researchers. Most of those students will come from classrooms other than mine. Therefore, I want all students to do well. But imposing a competitive business model creates a built-in contradiction where I benefit from the failure of other teachers’ students.

Enterprises that involve the public good are unavoidably collaborative, not competitive. Firefighting in big cities was once handled by private companies competing against one another. That model proved to be tragically (and sometimes comically) ineffective. These days, instead of competing, firefighters from different companies work together because it is in the common good. That is why firefighting is handled by governments.

As a teacher, I collaborate with other teachers on a daily basis. We share our best ideas. We take pleasure in the success of each other’s students. To us (and probably to you) the very idea of benefiting from any child’s failure is grotesque.

Here’s another example of how a competitive model is at odds with the premise of education: I came into this profession thinking that merit pay for teachers was a good idea. In the business world, it is common sense to pay your best employees more. Rewarding good performance provides incentive for all employees to work harder.

Something I have learned as a business owner is that money is not the most important motivator for many employees. This is certainly true for teachers.

Think of it this way. The type of person who is motivated by monetary reward is not going to be attracted to the teaching profession. When you become a teacher you accept that there is a limit to how much you can possibly earn and how high your status will ever be. The only way to change this is to leave the profession and become an administrator or a consultant.

If not money or status, what then motivates the best of us? It is the almost missionary belief that education is vital for children… not just for the children in our room, but for all children. Teaching, by its nature, is self-sacrificial. Our best moments come when somebody else succeeds.

If you were to offer me a bonus, $1,000, $10,000, even $100,000, I would gladly take it. But honestly, it would not make me a better teacher or make me work harder. I already work as hard as I can. I’m already doing everything I can do to be the best teacher I can be.

Some may want to label me as anti-reform. Nothing could be further from the truth. Our society’s whole attitude towards education is in great need of reform. Our educational system’s approach is in great need of reform. There are many alternative ways to think about reform. The folks who want to impose a business model are simply offering one alternative, and a wrongheaded one at that.

About the Author