Former Education Secretary Arne Duncan has a new book that opens with the provocative line, “Education runs on lies.”

"How Schools Work" examines not only Duncan's controversial tenure as Barack Obama's education secretary but the overall attitude toward public education in America, identifying a problem Georgia knows well: A divide exists between what we say we want for our schools and what we're willing to do and spend.

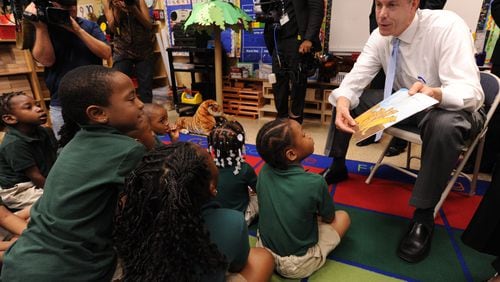

I met Arne Duncan several times in Georgia during his seven years leading the U.S. Department of Education. The 53-year-old was personable, bright and energetic.

I’m not sure he pursued the right path to fixing schools, but I also don’t know if schools can be improved from Washington or from the singular focus on teachers that girded the Race to the Top grants, one of which went to Georgia.

I read his book last week; it is quick and breezy and abounds in anecdotes about the failings of schools, policies and public will. Duncan’s account of Washington politics reinforces my doubts the federal government can ever lead education reform. School improvement can’t happen without rational discussion, and the national political scene has degenerated into a shouting match.

No matter how earnest an education secretary may be, edicts from the feds come across as something being done to schools rather than with them. Duncan attempted to persuade educators he was running alongside them and cheering them on to the finish line. But many believed he weighted them down by basing their worth on student test scores.

Here are excerpts from several recent reviews of Duncan’s book to give you a range of viewpoints: (With links to the full reviews.)

Writing for Education Next, Frederick Hess said:

Duncan does allow that mistakes were made during his tenure in Washington, confessing, "Some of our biggest problems were absolutely self-inflicted, and I'm happy to take the blame for them."

But an exhaustive catalog of these instances entails Duncan conceding that he once put his foot in his mouth by suggesting that "suburban white moms" opposed Common Core because their children were struggling to meet the new standards; that he didn't do enough to push universal pre-K; and that in several instances his team fell short in their public relations efforts, failing to adequately market their agenda. On the myriad controversies over federal support for the Common Core, the problems with test-based teacher evaluation, the dismal track record of $8 billion in federal School Improvement Grants, his dubious move to issue states conditional "waivers" from the requirements of No Child Left Behind, and more, he either doubles down or is utterly silent.

Duncan also revisits some familiar talking points with nary a nod to complexity or second thoughts. On Race to the Top, the administration's $4.35 billion grant program intended to spur states to adopt standards, linked assessments, and other reforms, Duncan explains that skeptics' concerns were misguided: "At the most basic level," he writes, "we were trying to get as many American kids as possible ready for college and careers." As for those who thought Race to the Top was an intrusive attempt to impose not-ready-for-prime-time dictates around teacher evaluation or school turnarounds, Duncan relates, "Many states were already undertaking this work—we called them the 'laboratories for innovation'—and all we wanted to do as federal employees of the Department of Education was help the states amplify and spread their success." Duncan never acknowledges that skeptics might have shared these goals but had good-faith doubts about Race to the Top or how he went about executing it.

Writing in The 74, Conor P. Williams, a fellow at the Century Foundation and founding director of New America's Dual Language Learners National Work Group, wrote:

While "How Schools Work" is full of smart ideas for U.S. public education, it's really about that Chicago parent meeting and the state of our union. It confronts one of the core premises of a healthy democracy: We can't get serious about improving our debates — let alone our policies — if we're unwilling to ever be persuaded. And, perhaps more important, we can't be open to persuasion if we're unwilling to let facts sway and compel us.

Back in 2015, when Duncan resigned, I worried that he was already stylistically and substantively out of step with U.S. politics. Here in Washington, I wrote, ours "is a world where self-effacement is usually career suicide, and where a man who genuinely isn't concerned about his standing in the polls or the newspapers is deeply confusing."

"How Schools Work" distills Duncan's ethos, and — implicitly — raises some of the biggest questions. Can we build a better education system simply by opening ourselves to research and caring a lot? Or are we doomed to corrosive fights that preclude us from having hard, uncomfortable conversations about what might actually help children? Because that's what Duncan thinks is the biggest lie: We tell ourselves that we care about kids. We don't.

In the Hechinger Report, Aaron Pallas, the Arthur I. Gates Professor of sociology and education at Teachers College, Columbia University, and former statistician at the National Center for Education Statistics in the U.S. Department of Education, said:

I don't doubt that Duncan cares about children and youth, and his attention to their well-being in this account is much more persuasive than those in the memoirs of Joel Klein or Michelle Rhee, colorful school reformers often mentioned in the same breath as Duncan. The chapter of his book devoted to gun violence and gun control is particularly compelling. But the personal travelogue he recounts, tracing his origins in Chicago through his tenure as the CEO of the Chicago Public Schools and then U.S. Secretary of Education, and into the present day, doesn't add up to much.

Regrets? He's had a few, but not too many. And even these lack much self-reflection. He's not a politician, he admits, but he has strong opinions about public policy, bolstered mainly by vignettes and anecdotes. A good story goes a long way, and issues often rise or fall on the policy agenda as much on the basis of stories as on hard evidence.

In the Wall Street Journal, journalist Naomi Schaefer Riley said:

Political memoirs are rarely tear-jerkers, but Arne Duncan's look back at his time as secretary of education under Barack Obama may make school reformers want to cry. It's not so much that Mr. Duncan, who served from 2009 to 2015 after a stint as head of the Chicago public schools, was bad at his job or in any way unprepared for its challenges. In fact, as "How Schools Work" makes clear, he understood a great deal about the problems plaguing American education. But that very understanding makes his cabinet tenure—recounted here alongside other tales from his public life—feel like a painful missed opportunity.

About the Author