Erica Turner is an assistant professor of educational policy studies at the University of Wisconsin who has studied the meaning of the Atlanta cheating scandal to families and students in southwest Atlanta.

By Erica Turner

The Atlanta Public Schools cheating trial came to a close after a Fulton County jury last week convicted 11 educators of conspiracy to falsify students’ test scores.

Credit: Maureen Downey

Credit: Maureen Downey

The decision capped a seven-month trial and years of investigation. You could almost hear a collective sigh of relief from city leaders and school district officials who have wanted to put behind them an episode that has “tarnished the image of the school system and the city,” as this newspaper reported.

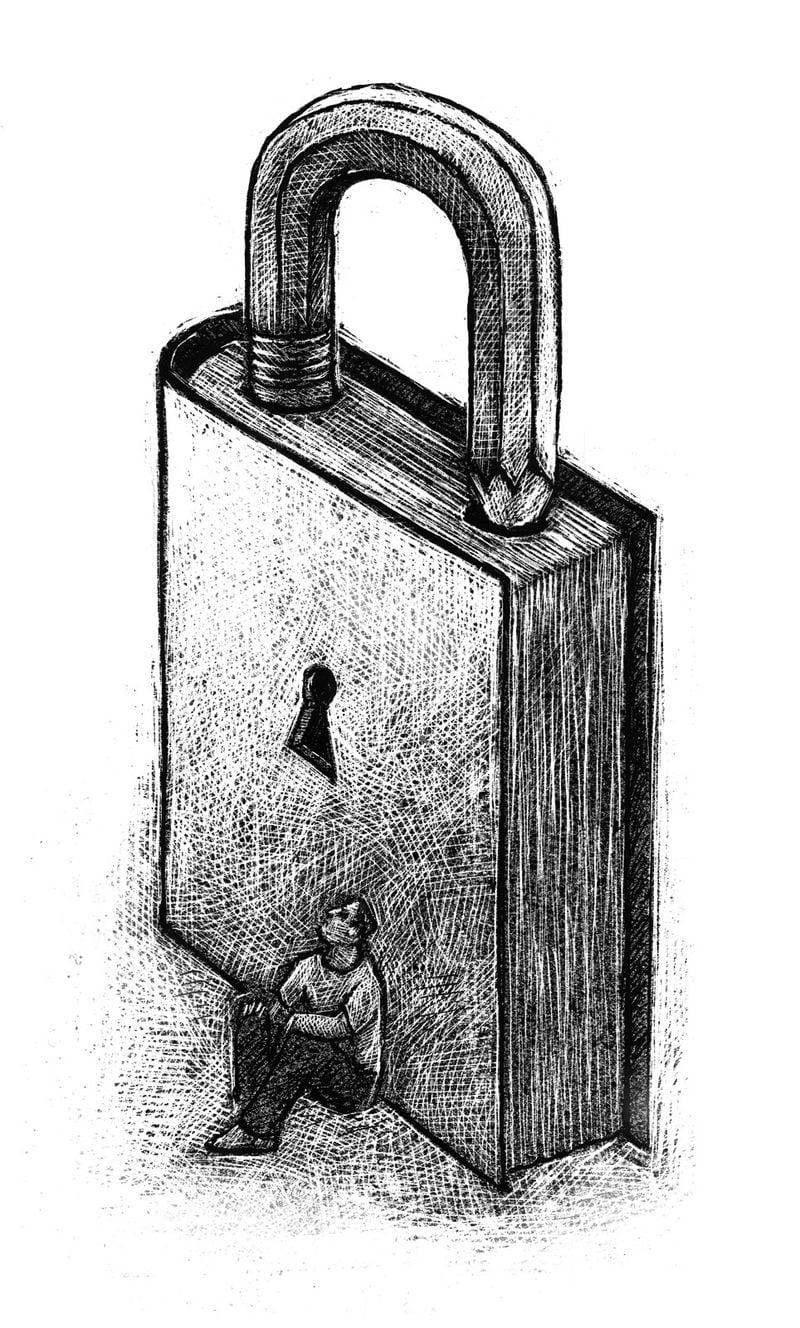

The trial was a spectacle that focused on the “who” and “how” of cheating, and diverted attention from understanding and improving the heart of the matter: the educational trajectories of APS students. Rather than closing the book on the cheating scandal, now is the time to focus on those children.

There is much still to learn and do.

Less than five minutes’ drive from the Fulton County Superior Courthouse, where the trial was held, the effects of the cheating scandal are not over. My research on the meaning of cheating among students, families, and their communities has identified that some youth believe that teachers think they are “not smart enough;” these youth have left school or remain in school but are struggling to keep up.

While I have interviewed parents who feel their children have not been harmed by this scandal, many parents feel an enormous sense of betrayal.

One mother asked me: “Who cares about these babies? Who cares about what happens to these children? Who has gone to go check up [on how they are doing]?”

While the school district has instituted new ethics rules and test security measures as well as a summer tutoring program, many children have not received adequate compensatory services. Community trust in the schools is low. The school district must provide students with the education they missed and rebuild that trust.

To compound this, in the southwest Atlanta community that has been the focus of my research, cheating is just one of many complicated circumstances contributing to children’s life chances. Health concerns, crime, and poverty have loomed large in my conversations with youth and families.

Educational research has demonstrated the ill effects of poverty on children’s well-being and academic achievement; families too are well aware of these effects. In my interviews with families, neighborhood safety and health concerns—such as asthma and lead — were repeatedly mentioned. These circumstances make it difficult for youth to learn and hard for teachers to raise student test scores.

Amidst these challenges, some students have received important supports, sometimes from the same schools where cheating occurred. One young woman described her school not as a barrier to success but as her second family. She described teachers, some who later admitted to cheating, who provided students with extra tutoring, afterschool activities, meals, safe rides home, respect, and sometimes even a place to live.

In addition to many educators, a few community development organizations, neighborhood activists, and the Annie E. Casey Foundation have been trying to provide support for these children. While efforts are being made to assist this neighborhood’s residents, the city services regularly provided in other parts of town are not always present here. It is painfully obvious more comprehensive support from local government is needed.

Listening to youth also brings to light the inequality of educational experiences and resources made available to different groups of children in Atlanta’s schools. Youth who attended schools where cheating occurred describe an incredible emphasis on testing, test preparation, and rote learning intended to help students improve standardized test scores.

In addition, the resources at their schools for educational trips, band instruments, and the maintenance of recreational facilities were deplorable in comparison with the predominantly white and wealthy schools to the north of them.

A former student noted, “Kids were being disserviced…far before the cheating scandal ever happened, and are still being disserviced. There has been no plan instituted to…give urban schools better infrastructure. It was just about making them look like they’re responsive…they really care, but they don’t.”

While these youth viewed the education they received as quite good, they were well aware that they received a less than equal education.

To be sure, test security is important and cheating should not be condoned. However, if we want to improve children’s educations and lives, then the lessons we take from the cheating scandal in Atlanta cannot be limited to test security and punishing a few bad apples.

The focus on cheating distracts us from understanding the conditions shaping the lives and opportunities of children who attended schools where cheating occurred. A focus on children, and listening to them and their families, brings those conditions to light. It also makes it clear that there is still plenty of work to be done. The school district can provide needed educational services and repair trust with communities. The city can extend greater social support and services to these neighborhoods.

However, it will take policymakers and citizens to ensure an equitable education: committing to educational resources across APS schools and rejecting the high stakes policies that promised to address educational inequality but have failed to do so. That is to say, addressing the inequalities at the root of the cheating scandal—at the root of the conditions shaping these children’s lives — requires a broad, civic, state, and federal effort. This work needs to start now.

About the Author