The voice of Annie is still in his head. He hears her as he works daily to put his life back in order, when he travels the world to give speeches, when he talks to his children about success and failure, having become an expert at both extremes.

Work hard. Be responsible. Own up to your mistakes.

“‘Pay attention,’” Evander Holyfield said, smiling. “I can still hear her saying those words. Sometimes people, they’ve done some bad things, but I’m not going to falsely accuse them when I talk to them today. I pay attention because I know every day is a new day. I’m proof.”

Annie Holyfield wasn’t just Evander’s mother, she was the strongest influence in his life, the only person he ever feared. Holyfield was a momma’s boy and proud of it. She demanded good conduct in school, high character in life, kindness, forgiveness.

“Work harder than everybody else, and 99 percent of the time you’re gonna catch them,” Annie told him.

She wrote his life story.

“It’s amazing when I think about it: Everything she said was right,” Holyfield said.

Holyfield caught them all during his boxing career. He lost 10 times in 57 bouts, but he was defined by his comebacks, his sheer will and courage, winning some of the biggest fights in the sport’s history. He beat Mike Tyson twice, Riddick Bowe, Michael Moorer, Dwight Muhammad and more, fighting everybody of significance in his era. For those reasons, he was voted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. Induction ceremonies are next week in the small village of Canstota, N.Y.

What would Annie say?

“She’d say, ‘I told you. You do something good and that will be waiting on you,’” he said. “She told me, ‘A good attitude is better than talent.’”

Annie Holyfield died in 1996, the result of injuries stemming from a car accident seven weeks earlier. She seldom watched her son box because it made her too nervous, but she lived long enough to feel the pride of him making the Olympic team, winning a medal and going on to have one of the more successful careers in boxing history as cruiserweight and heavyweight champion (a record four times).

She was not there to see her son’s financial fall, coming after ill-advised business ventures, three failed marriages and too many instances of trusting the wrong people, including family members who stole from him. It all led to the loss of his fortune and send his Fayetteville mansion into foreclosure. But she was in his ear when he hired an accountant to go over his finances and was told money had been stolen by relatives who worked for him.

“My momma said, ‘Be responsible for what you did. You know what was happening.’ I had a big accounting firm tell me, ‘Somebody in your family is stealing. They got $3 million.’ I told them I can’t (turn in) kin folk. They got $3 million. I’ve still got $32 million. Let them go.’”

That was when he still had $32 million in the bank. Most of the $250 million in boxing purses he earned in his career is now gone. But he is good today.

“I’m in the second half of my life now, and my second half is going to be better than my first half.”

He’s 54 years old. His chiseled body still gives the impression he has never eaten a Twinkie. He works out daily, often at the Fort Lauderdale boxing gym. His three-pronged workout: elliptical machine, shadow boxing, heavy bag.

Workout time: 12 rounds, 36 minutes.

He lives in south Florida when he’s not traveling and giving speeches, which earns him a nice living. He moved from Atlanta at the invitation of a friend, who owns a boxing gym and has ties to the Hard Rock Casino across the street. Holyfield makes appearances and poses for pictures. Everywhere, he poses for pictures.

“God isn’t going to ask me, ‘How many times were you heavyweight champion of the world?’” he said. “But God will ask me, ‘What did you do for other people?’ I’m going to tell him, ‘I took pictures.’ And He’ll say, ‘Come on in.’ ”

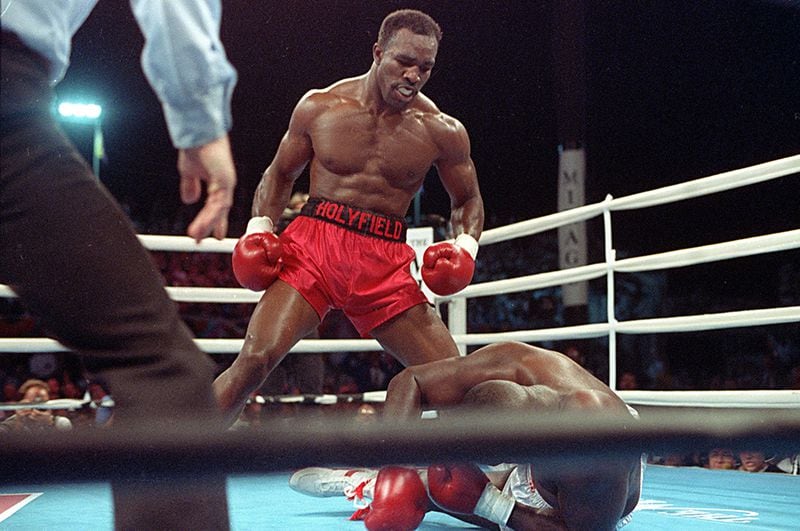

Credit: DOUGLAS C. PIZAC

Credit: DOUGLAS C. PIZAC

Holyfield needed to start fresh in another city. He needed to get away from family members who had become overly dependent on him, even though he still flies to Atlanta weekly to attend church.

“Abraham said, ‘Get away from the kin folk,’” Holyfield said. “I was trying to keep Holyfield a good name.” (The actual Bible verse: “God appeared to Abraham … and told him, ‘Leave your country and your kindred and go to the land I will show you.’” Just substitute Mesopotamia with Atlanta and Haran with Fort Lauderdale.)

People will forever ask: What happened to the money? Holyfield doesn’t ask. He knows.

“I had people doing things who didn’t know what they were doing. But I have to be accountable.”

And then: “The reason I even made it that long was I had my momma to protect me. Nobody in the family, even business people, could ask me anything without going through her.”

Bad investments, three divorces, child support for his 11 children that at one time cost him up to $500,000 annually. He tried to start a record company. That cost him more than $3 million. The biggest financial misstep was his decision to become a majority investor in the Black Family Channel, a failed venture by former Atlanta attorney Willie Gary.

Holyfield lost approximately $50 million. “That pretty much crushed him,” one friend said.

That’s how $250 million in boxing purses evaporates. He never filed for bankruptcy, nor was he ever destitute. But he was forced to foreclose on his $20 million, 54,000-square foot mansion that sits on a street still named for him: 794 Evander Holyfield Highway is now owned by rapper Rick Ross, who bought it from the bank on markdown for $5.8 million.

When Holyfield lived there, he was told it cost an estimated $1.2 million per year for normal upkeep. But he wants that home back. He dreams of returning to Atlanta and moving back in.

“I’m gonna buy that house back eventually,” he said. “I built it for my grand kids. Maybe make it into a museum.”

Dreams have never been his problem.

His journey has seen more extremes than most. He grew up poor, sometimes going to school with holes in his clothes and saying little in class in hopes of not drawing attention to himself. When he hit bottom again, those memories actually comforted him, knowing he could rebound.

“I was brought up on nothing,” he said. “When I was working three jobs and making $8,000 a year, I thought I was doing good.”

Some believed he was broke, but he always had money in the bank. “I saw no reason to say anything. Let people believe what they want. My kids kept going to private school. I just wanted time to get everything together.”

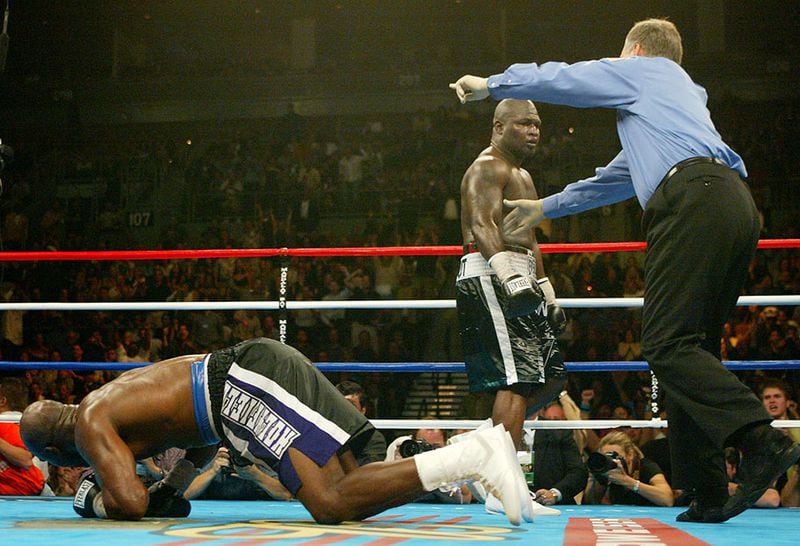

Credit: ERIC JAMISON

Credit: ERIC JAMISON

He’s doing that. He reunited with longtime friend and attorney Jim Thomas. The two split when Thomas suggested he retire following a loss to James Toney in 2003. (It was the correct advice, just not what Holyfield wanted to hear at the time.) Thomas was unique among Holyfield’s family and friends: He never stole from him, never misled him and always had his back.

“It was like being divorced from your brother,” Thomas said of the breakup, thankful the two are back together.

Holyfield also has become a partner in a promotion company: “Real Deal Championship Boxing.” He sold his name and likeness, but didn’t have to invest a nickel. The first show is June 24 at Freedom Hall in Louisville, home to the Muhammad Ali Center. Ali was a hero to Holyfield.

“He said he was the greatest. And you know what? I wanted to be the greatest,” Holyfield said at the announcement.

Ali, Joe Louis and Rocky Marciano are probably the three greatest heavyweight champions of all time. Holyfield’s place in history is often debated, but he’s in the argument for top 10. They fought everybody, and the fact he lost 10 times was mostly the residual of hanging around too long (five losses in last 12 bouts). People forget Ali lost three of his last four, Joe Frazier four of his last eight.

Boxers have trouble accepting the last dance.

Holyfield’s final bout: a win over Brian Nielsen, in Copenhagen, Denmark, on May 11, 2011. It was an ugly event. He was 48; Nielsen was 46 and coming off a nine-year layoff. Nielsen was a schlub. Holyfield stopped him in the 1oth.

But that was it. Holyfield had quietly decided in camp it would be his last time in the ring. His sparring partner kept beating him to the punch. “I couldn’t even get mad at him,” he said.

So he let go of his fantasy of retiring as undisputed champion.

“No regrets,” he said. “I quit at the right time.”

Don’t cling to the memory of the end of Holyfield’s career. Celebrate all of those fights that earned him induction.

The 15-round battle with Dwight Muhammad Qawi in The Omni for the cruiserweight title in 1986, when Holyfield suffered severe dehydration and was happy to just survive. (“It’s the closest I came to quitting.”) The knockout of Henry Tillman in his first bout as a heavyweight. The first heavyweight title knockout of Buster Douglas. The avenged victories over Riddick Bowe — their first two fights were among the greatest in history — and Michael Moorer. All of the obstacles he overcame, including a deranged paraglider crashing into an outdoor ring in the second Bowe fight and licensing boards wanting to handcuff him to a hospital bed following a misdiagnosed heart ailment.

“He was like the book every kid reads: ‘The Little Engine That Could’,” said former trainer Teddy Atlas, a boxing historian and ESPN analyst. “Over and over again, he was not supposed to do what he did. He never made excuses, he just found a way to get it done. That had to come from somewhere. It came from his mother. She understood what her son would face. He would be held accountable. That’s the difference between him and Mike Tyson. Tyson had the talent, but he wasn’t accountable.”

The Tyson fight in 1996 was Holyfield’s opportunity to gain the universal respect that had eluded him. He was considered at the end of his line and was an overwhelming underdog. But he stopped Tyson in the 11th round, then exposed him as a coward in the rematch when Tyson twice bit his ear and was disqualified.

Holyfield raged over the incident, but eventually found humor in his missing a chunk of his ear. When a doctor suggested plastic surgery, Holyfield declined: “Everybody says I’m too nice. I’ll get the other one to match, and then I’ll look like a Doberman Pinscher.”

The first win over Tyson stunned the masses. But Annie, who had passed months earlier, had prophesied it.

“He’ll be the easy fight,” she told Evander long before.

He looked at her sideways.

“I said, ‘You don’t understand. He’s knocking everybody out,’” Holyfield recalled. “She said, ‘But he’s getting in all that trouble. It shows he can’t handle pressure. When you put that pressure on him, he’s gonna blow up.’”

She was right about Tyson. She was right about her boy. Holyfield will take those memories with him to the Hall of Fame.