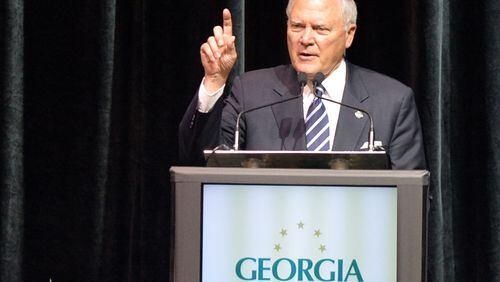

When Gov. Nathan Deal handed in his list of last-minute additions to the state budget earlier this year, it included $10 million to buy land in Gainesville for a new technical college campus in his hometown.

The money was a down payment on the legacy Deal is building as he heads into the second year of his final term as governor. That legacy includes his nationally acclaimed criminal justice reform and, he hopes, a new school funding system.

It will also include a big tab for pet projects that will continue costing taxpayers long after he’s gone. Besides the new technical college campus, which could eventually cost $100 million or more, the former attorney, prosecutor and judge is expected to push for a new state courts building — probably the most expensive building in state history. Both will likely be done on borrowed money that won’t be paid off until the 2030s.

He's also expanded the Court of Appeals, and is pushing to enlarge the Supreme Court, both of which have long-term costs. There are also plans for new ports infrastructure and possibly increasing the $75 million that Georgia has already invested in restoring state-owned Jekyll Island's lost luster. And there are plans for reservoir in his home Hall County that could cost tens of millions of dollars more.

Deal is following in the footsteps of predecessors who pushed for parochial projects in office. Gov. Zell Miller championed a taxpayer-financed mountain retreat in his hometown of Young Harris. Gov. Roy Barnes backed a state-funded amphitheater project in his hometown of Mableton, and money to study a revamp of the Cobb hamlet.

Sonny Perdue, the state's first Republican governor since Reconstruction, retired from office with a last-minute, costly purchase of woods adjacent to his Houston County property and the Go Fish Center down the road from his home. The state still owes $13 million in debt payments on Go Fish, and will be paying it off until December 2027.

Some of Deal’s building projects could be among the costliest in state history, with the technical school move from South Hall County to North Hall County alone costing more than the state typically spends on building projects for the entire technical school system in a year.

But such local projects have long been part of the system that rewards both supporters and the hometowns of the politicians that rise to power.

“Wallflowers don’t get elected to anything, people with big egos do,” said Tom Bordeaux, a Savannah city alderman who was a floor leader for Miller in the state House. “Big egos like to read their names on something.”

Tom Lewis, who served as Gov. Joe Frank Harris’ chief of staff, said, “It is rare in modern times that a governor does not build something in their hometowns.”

But lawmakers say Deal has so far not pushed for anything like Perdue's Go Fish Center, an education and tourism facility that has attracted much public derision and relatively few visitors. Months after it opened in October 2010, the New York Times dubbed it a "symbol of waste" at a time when lawmakers were slashing education and social services in reaction to the Great Recession.

While some of Deal’s projects — past and current — may cost the state for decades, supporters argue none are frivolous.

A new campus for Lanier Tech

They cite the relocation of Lanier Technical College as a prime example. The State Properties Commission, which is chaired by Deal, agreed to spend about $6.4 million to purchase about 85 acres for the new campus.

The school is moving from its main location in Oakwood, where its held classes regularly since the 1960s, to the new property less than 10 miles away. The new campus will be built from scratch.

Deal casts the project as a way to help focus on manufacturing jobs, to prepare Georgians to work at the new plants, such as the Kubota, a leading manufacturer of small tractors, lawn mowers and recreational vehicles, in the area.

Kubota announced just before last year’s election that it was expanding into an industrial park with ties to the governor’s campaign chairman. A state panel Deal heads decided in 2012 to build a new poultry laboratory in the same industrial park.

Deal said he expects the new school to meet the state’s need for a more skilled workforce.

“The opportunity to have a new and redesigned and an expanded building is a great asset. The new facility will hopefully be a state of the art facility. It’s ideally situated,” said Deal, who predicted the school funding won’t be a hard sell to legislators.

As for whether it will burnish his legacy, Deal is straightforward.

“I’m always proud of anything we do positive in the state of Georgia. Just the fact that it happens to be in the county where I have lived for many years, I suppose there’s some satisfaction to that,” he said, before adding: “But it is a growing part of the state. That’s one of the driving forces.”

Surprise, questions greet campus move

Still, some Gainesville residents said they were surprised when Deal publicly broached the idea of the move late in the 2015 legislative session. At this time last year, it wasn’t on a lot of people’s radars.

“I won’t say I expected it, but this was something I was very hopeful would happen,” said Ray Perren, president of the 3,600-student college.

Deal didn’t include the money for the school in the budget he proposed to lawmakers in January, the spending plan legislators debated for almost three months before approving. Instead, he added the money at the last minute.

Governors frequently do that, limiting time for debate or responding to last-minute requests. A few years ago Deal did the same thing when the World Congress Center asked late in the session for money to begin construction of a parking deck to be used by Falcons fans heading to the new downtown stadium.

Perren said the move will give the school the chance to support new programs in the heart of its four-campus service area. The new school could have six buildings and add or expand several new programs, including ones for commercial truck driving, hospitality and industrial maintenance.

The current facilities, he said, are “adequate, but they are dated.” He noted that the school sits on the backside of the University of North Georgia-Gainesville campus. “We are looking for something that gives us more of an identity.”

Some locals questioned the decision.

Jerry Jackson, a former legislator who lives in Chestnut Mountain, said in a letter to the Gainesville Times that the idea to move the technical college came out of nowhere.

He said the school is currently located in a part of the county near Gwinnett and Forsyth counties, drawing residents from those two fast-growing areas. Taxpayers invested more than $80 million on a new interchange and four-lane roads to connect two I-985 interchanges with the University of North Georgia and Lanier Tech, he wrote.

“There is no doubt the buildings (at Lanier Tech) need renovating, updating and possibly some additions,” he wrote. “But a study needs to be done and a lot of public input heard before this school is moved.”

One Deal supporter, Doug Magnus, president of Conditioned Air Systems Inc. in Gainesville, offered the state land to rebuild in hopes of keeping the school near its current location.

Instead, the state paid for land owned by an Atlanta real estate company that Capitol lobbyist and former Perdue chief of staff John Watson advises. Watson said he had no financial stake in the land and wasn’t involved in the deal.

State technical college officials said they will ask for $75 million in borrowing for the project over the next two budget cycles. Perren said the total cost could run about $100 million. If it’s all done in 20-year bonds, the state will wind up making $180 million or so in debt payments. Taxpayers will be making payments on the bonds into the 2030s.

Sensitive to perceptions

Not far away is another of the governor’s pet projects, the proposed Glades Reservoir project, about seven miles north of Lake Lanier — smack in Deal’s Hall County.

It’s a cornerstone of Deal’s plan to boost Georgia’s water reserves, though critics say it’s a costly and environmentally damaging construction that’s no longer justified given that new population projections that show much slower growth for the region. Estimates put the cost at $130 million, although it’s unclear how much state funding would be involved.

Building such a hometown legacy isn’t usual for governors.

George Hooks, a legislative historian who served with Deal in the Georgia Senate, said the governor is probably getting pressure from hometown leaders to do more for his county.

“People are going to come calling, they are going to want this, that and the other thing,” Hooks said. “He’s done some things for Gainesville, but I don’t think he’s done any more than any other governor would have done.”

Hooks said, for instance, that Gov. George Busbee, who served from 1975 to 1983, was responsible for completing a freeway from I-75 to Albany, where he lived. Decades before, Hooks said, Gov. Marvin Griffin was instrumental in building an inland port in his hometown of Bainbridge.

Perdue was heavily criticized once he left office for all the money he steered to his home county, Houston, in central Georgia. But Watson, his former chief of staff, said Perdue’s home folks may have lost out on some projects because the administration didn’t want to appear to be favoring locals too much.

“You’re always sensitive about the perception that you are giving everything to your home community,” Watson said.

New court buildings to come

Legislative leaders have been quick to go along with Deal’s funding proposals in part because he’s given them some money for projects of their own. He typically sets aside $100 million in borrowing for lawmakers to pick and choose their own projects. The strategy not only gives lawmakers buy-in and reason to support Deal’s proposals, it provides legislators with something to brag about at home come election time.

Deal sold legislators on a park-like gathering area called Liberty Plaza across from the Capitol where an unsightly parking deck had stood since the mid-1950s.

On a much larger scale, Deal got lawmakers to budget money to begin designing a new building for the state's Supreme and Appeals courts he hopes to expand. It would be built on the site of the former state archives building a block from the Capitol. And it may cost $115 million, or more, to build, the equivalent of about $200 million in bond payments over the next 20 years.

It could be the most expensive state-funded building ever and Deal is expected to push to fund it before he retires in January 2019.

Some lawmakers dispute the idea that Deal is looking to get his name attached to fancy, expensive new buildings or reservoirs so he’ll be remembered when he’s gone. They say the governor is just building what he thinks the state needs.

“I don’t really sense that Governor Deal is so much focusing on a legacy as focusing on what he believes is best for the state,” said state Rep. Joe Wilkinson, R-Sandy Springs. “I work pretty closely with him, and I’ve never once heard him say, ‘I hope people remember me this way.’ He’s not going to be a Rudy sitting around bars talking about the glory days.”

About the Author