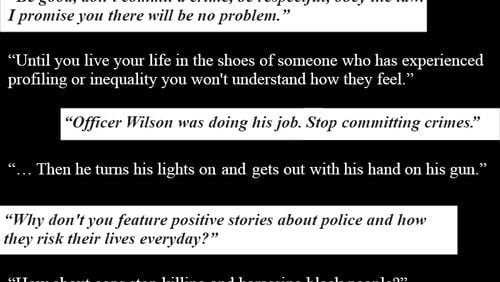

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution invited readers to share their thoughts on the relationship between police and the black community. To read the responses and join in the discussion, go to: https://www.facebook.com/ajc/photos/a.82934412298.77711.13310147298/10152828807602299/?type=1&theater

When white people talk about the death of Michael Brown, they talk about facts. When black people talk about it, they talk about reality.

They are not the same thing.

Deena Mann Maxson of Hiram looks at the facts of Brown’s shooting: that he reached into Officer Darren Wilson’s car, that he was facing and perhaps advancing on Wilson when he was killed. She does not see what happened in terms of race.

“Brown committed a crime and assaulted and attacked Officer Wilson when questioned. Officer Wilson was doing his job. Stop committing crimes and there won’t be an issue,” Maxson said.

Wade Clark of Duluth looks at the reality of Brown’s shooting: that black people are far more likely to be shot by police than white people, that many African-Americans have felt the indignity of being challenged by police or store security for merely being “out of place.”

“You very rarely see white guys getting shot like this,” said Clark, 32.

That’s not to say that black people have ignored the facts of the Brown case. They question, for example, the unusual nature of the grand jury that heard evidence against Wilson, and also the way the evidence was presented. All of which reinforces, for many, the idea that the Brown shooting was less an isolated event than a point on a long and dismal continuum.

White Americans and black Americans can look at the same thing and see something quite different — not because of what they’re seeing but because of where they’re standing. Those remarkably different perspectives lead to misunderstanding and frustration on both sides.

Stacey Hopkins, 51, an African-American mom in Hapeville, says she had “the talk” with her son when he was about 14.

She recalls it going something like this: When you were younger I told you how the world should be. The people are kind and do the right thing. Now I'm going to tell you how it really is. You are a born suspect.

That reality, Hopkins says, is lost on most white people.

“We have totally different perspectives,” Hopkins said. “There are all these perceptions: we steal, we’re thugs, we’re on welfare. You would think we’re uncouth beasts. That is the heart of the problem.”

Bridging that divide between those perspectives will not be easy, but even in the heat of moments like these, some people, police included, are determined to try.

‘Being a police officer is a very scary job’

Much of the conversation relates to the relationship between the police and the black community. The work of scholars and government analysts is awash in statistics about the intersection of race and justice.

Here is perhaps the most stark: Black teenagers are at 21 times greater risk of being shot dead by police than white teenagers, according to a report last month from the investigative journalism website ProPublica. The analysis examined 1,217 deadly police shootings included in federal law enforcement data from 2010 to 2012.

As an African-American, Wade Clark believes some whites look at him and see every black criminal they’ve seen in the news. “You see one do a bad thing and we’re all judged. We have to constantly prove ourselves. It’s frustrating,” he said.

Bill Florence, 57, lives in Dunwoody, but he used to work in Clayton County as prosecutor. Florence, who is white, said racial perceptions may have influenced Officer Wilson’s behavior.

But he said it’s important to weigh his actions in the context of a police officer’s experience.

“Let’s face it, being a police officer is a very scary job,” he said. “You never know when it might be your last minute or somebody else’s.”

Faced with making split-second decisions, an officer can’t stop and evaluate whether racial stereotypes are clouding his or her judgment, he said.

“You can’t think about the socioeconomic forces at work, because a bullet could be coming at you,” he said.

‘Driving while black’ in America

Deaths like Michael Brown’s are relatively rare. At the other end of the spectrum are simple traffic stops, the most common interaction between all citizens and police.

In its most recent survey, in 2011, the federal Bureau of Justice Statistics found that 12.8 percent of black drivers reported being stopped by police in the past year; for whites, the number was 9.8 percent. Twice as many blacks (32.5 percent) as whites (16.4 percent) believed they were stopped for no legitimate reason. They were equally likely to feel that way whether the officer was white or black.

Once they were stopped, black drivers were more than twice as likely to be searched and also more likely to be ticketed.

Among African-Americans, “everybody has stories” of the perils of “driving while black,” said Carol Anderson, an associate professor of African-American studies and history at Emory.

For her, one such incident occurred while she was driving accompanied by a white friend in the friend’s neighborhood. Anderson made a quick turn and the police lights appeared behind her. Her friend started railing that she had made that quick turn often without any trouble, that Anderson being pulled over was just wrong.

Her outrage didn’t comfort Anderson; it scared her, because she feared it might inflame the cop. “I was like, ‘Shut up,’” the scholar recalled. “(My friend) is not going to get shot. I can easily be shot. My Ph.d doesn’t matter.”

‘They should start asking questions’

Researchers have reported for decades that African-Americans make up a disproportionate share of people arrested, convicted and imprisoned in this country.

What’s difficult to know for sure is why.

No one is arrested for the vast majority of reported crimes, so there’s no way to know the races of the ones who evade prosecution. That opens the possibility that racial bias is behind the discrepancies in arrests and convictions. But it doesn’t prove it.

Perhaps, in a country that is majority-white, lawmakers, police, prosecutors, judges and juries do share an opinion that black people are inclined toward criminality. Even if that bias is unconscious, the likely result — blacks more likely to be caught and prosecuted than whites — would only reinforce the belief.

“It’s certainly something that should get your attention and you should start to ask questions,” said David A. Harris, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh school of law who is an expert on racial profiling, police conduct and accountability. “Does this reflect discrimination? You can’t make that judgment without knowing more. But a pattern of disparity should be enough to make police departments, courts, whoever, they should start asking questions about whether they have a problem.”

‘Biased policing is not legitimate policing’

It’s also possible that the circumstances in which black people commit crimes — for instance, the open-air drug markets that plague some low-income neighborhoods — make criminals who operate in such settings easier to catch. And, once caught, they are less likely than whites to have the money to hire a skilled defense lawyer.

When it comes to the fraught relationship between African-Americans and police, it may be that both sides come to any encounter primed with suspicion, expecting the worst. Sadly, our expectations sometimes affect our behavior in ways that turn those expectations into self-fulfilling prophesies.

Some leaders in law enforcement are sufficiently worried about the reality or perception of bias to have created a working group designed to research and prevent it.

“Biased policing is not legitimate policing and leads to mistrust in the communities that most need effective law enforcement services,” said a report from the group, the Consortium for Police Leadership in Equity.

“This perception is driven in part by historical realities and in part because the percentage of stops that result in valid arrests tend to be relatively low and the number of innocent racial/ethnic minorities subjected to police stops, frisks, and searches tends to be relatively high.”

‘Staggering disparity’ in arrest rates

The Ferguson shooting spurred a flood of fresh analysis that reinforced the findings of previous research.

Just this month, USA Today identified a “staggering disparity” in arrest rates based on race in communities across the country, based a nationwide analysis of arrest data.

In Ferguson, blacks are almost three times as likely to be arrested as non-blacks. The newspaper’s analysis found more than 1,500 communities, including some of the largest in metro Atlanta, with even greater disparities between white and black arrest rates.

In Atlanta, the arrest rate is more than five times greater for blacks. In Sandy Springs and Marietta, it’s more than three times higher. In areas patrolled by DeKalb County Police, arrest rates are more than four times higher for blacks. For Clayton County Police, it’s five times higher. Among the jurisdictions included in USA Today’s analysis, Acworth was the only place in the five core metro counties with no racial disparity in arrest rates.

Another recent report, by scholars at Stanford, sheds a startling light on one impact of such statistics. In their study, the data didn’t make whites favor reforms; rather, they increased support for get-tough-on-crime policies.

The toll of the war on drugs

In the U.S., the “war on drugs” epitomizes those policies. After the war began in the 1980s, drug offenses became the leading source of convictions in the United States.

Drug offenses are also one area where it’s possible to test the justice system for bias. That’s because independent data, gleaned through large, anonymous surveys, show how many people use drugs and which types they use.

Contrary to popular perception, by far the most common drug crime prosecuted in the past few years has been possession of marijuana. Although surveys show that whites and blacks use pot at nearly the same rate, blacks are 3.7 times as likely to be arrested for possession, according to an analysis by the ACLU.

In Georgia, 65 percent of all drug arrests in 2010 were for marijuana possession. Sixty-four percent of those arrested were black.

In the 1980s and ’90s, cocaine was the target of legislators, prosecutors and police. As crack began to flood into poor neighborhoods, Congress passed a series of laws designed to stem its rise. One set the minimum sentence for possession of 5 grams of crack at five years but left the maximum sentence for possession of any amount of powdered cocaine at one year.

Subsequent federal studies found that more than 80 percent of inmates serving time for crack were black, even though studies showed the majority of users were not. Data also showed that blacks served roughly as much time for nonviolent drug offenses as whites did for violent crimes.

‘They’re going to get pulled over’

So, back to this facts-vs.-reality thing.

In many instances, whites and blacks do seem to be talking past each other from different planets. But that doesn’t mean they can’t reach beyond the boundaries of their own experiences and grasp the nuances of a complex and intractable problem.

Ronnie Burden is 46 and black. The Decatur resident thinks police sometimes shoot black suspects “at the drop of a hat,” but he acknowledged that some young blacks bring trouble upon themselves.

“Our youth, some are very much out of control,” he said.

Myna Helfont is 86 and white. The Sandy Springs resident thinks the way many young black men present themselves is a provocation. “If these kids want to look like gangsters, they’re going to get pulled over,” she said.

But, she, too, sees another side to the story.

“(Blacks) don’t trust the police and there are incidents in which innocent young boys are pulled over. It leads to a lot of distrust,” Helfont said.