Bill Pryor, on President Donald Trump’s short list to fill a U.S. Supreme Court vacancy, has left a trail of writings and statements that will inflame liberal interest groups across the country.

But unexpected resistance from social conservatives appears to have moved Pryor, who sits on the federal appeals court in Atlanta, from front-runner to member of the pack. Such resistance, which arose only recently, seemed unimaginable given Pryor’s past positions on the touchstone social issues of the day.

» Judge Pryor's Miracle on 34th Street

Pryor, 54, has called Roe v. Wade, the 1973 case legalizing abortion, the “worst abomination in the history of constitutional law.” And he once wrote that the right to engage in same-sex relationships would “logically extend to activities like prostitution, adultery, necrophilia, bestiality, possession of child pornography and even incest and pedophilia.”

Pryor’s opinions as a federal judge are devoid of such incendiary rhetoric and indeed are more nuanced than his earlier statements might suggest — a fact that may cost him with social conservatives.

Because of his earlier statements and writings, Pryor would have a tough time winning Senate confirmation, said Nan Aron, president of the liberal Alliance for Justice. “There’s something in his record to offend every constituency in America, except perhaps the hard right.”

But even the hard right has placed Pryor in a crossfire that may sink his chances for the nomination. He’s being criticized by evangelical groups for decisions he made in a few gay rights cases. This includes a 2011 ruling in favor of a legislative editor at the Georgia General Assembly who was fired after disclosing she was going to make the transition from a man to a woman.

Pryor’s supporters point to his fidelity to the Constitution. They note that he took some unpopular positions — some of them contrary to his own views — while serving as an Alabama attorney general in support of the rule of law. That included a highly publicized smack-down of the state’s chief justice justice, who’d refused to abide by a court-ordered injunction regarding the Ten Commandments.

“I fully expected he’d get blistered from the left, but I never expected this,” said John Malcolm, a former federal prosecutor in Atlanta who now works for the conservative Heritage Foundation. “It’s a shame, because I think he’s an excellent judge. Bill Pryor has a titanium steel spine and is someone who’ll do the right thing. But I think the attacks from the right are hurting him.”

A boost for Pryor from Jeff Sessions?

Atlanta lawyer Kyle Wallace, who once clerked at the Atlanta appeals court, said Pryor’s judicial philosophy is akin to conservative U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito’s.

“Bill Pryor has a strong belief in originalism, the text of the Constitution and judicial restraint,” Wallace said. “He follows the law as it’s written.”

When Pryor met with Trump in New York at Trump Tower shortly before Inauguration Day, it looked as if the judge was almost a shoo-in to succeed Justice Antonin Scalia, whose seat has remained open since Scalia died last February.

But in recent days, the names of other potential nominees have surfaced. The one who seems to have gained the most traction is Judge Neil Gorsuch, 49, who sits on the federal appeals court in Denver. Also said to be on Trump’s short list: Judge Diane Sykes, 59, of the federal appeals court Chicago; and Judge Thomas Hardiman, 51, of the federal appeals court in Philadelphia.

“We will pick a truly great Supreme Court justice,” Trump recently told reporters at the White House.

If it does turn out to be Pryor, it could be because of support from Alabama Sen. Jeff Sessions, Trump’s nominee for U.S. Attorney General.

Pryor worked for Sessions when the latter was Alabama’s attorney general and then succeeded Sessions when he became a member of the Senate in 1997.

A strong opponent of abortion rights

Pryor, a native of Mobile, was raised in a devout Catholic household by parents who were JFK Democrats and outspoken opponents of segregation. Two memorable incidents in Pryor’s life help explain his unwavering opposition to abortion rights.

One occurred when Pryor was 10. That’s when he witnessed his parents’ shocked reaction to the U.S. Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision that legalized abortion. In 1988, after some investigation, Pryor learned that his own father was adopted and that Pryor’s biological grandmother had been an 18-year-old waitress in Savannah who had given up her baby.

In a 2003 interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Pryor’s father said he’d often wondered what would have happened if abortion had been legal when his young mother was pregnant. “I thank God I had laws to protect me,” he said.

This may explain why Pryor, at his 2003 Senate confirmation hearing for the federal appeals court judgeship, doubled down on his hatred of Roe v. Wade. “Not only is it unsupported by the text and structure of the Constitution … it has led to to the slaughter of millions of innocent unborn children,” Pryor said. But he also pledged to follow the law.

At Tulane University law school, where he graduated magna cum laude, Pryor founded a chapter of the nascent Federalist Society. Now one of the nation’s most influential conservative legal organizations, the society espouses that judges should interpret the laws, not make them.

Pryor has become one of the Federalist Society’s go-to experts. He’s a frequent speaker and moderator at its events.

Speaking to a Federalist Society seminar two years ago, Pryor said one example of his adherence to the rule of law can be traced back to when the state Legislature enacted a law that said students could pray in a non-sectarian, non-proselytizing way at school events. As state attorney general, Pryor was expected to defend the law but he chose not to.

“Now, I’m not a theologian, but I’m not sure what a non-sectarian, non-proselytizing prayer would look like,” he said. “But I was pretty sure that was viewpoint discrimination, that that was choosing one form of prayer over another and that it violated the First Amendment.”

Credit: AP FILE

Credit: AP FILE

The Roy Moore case in Alabama

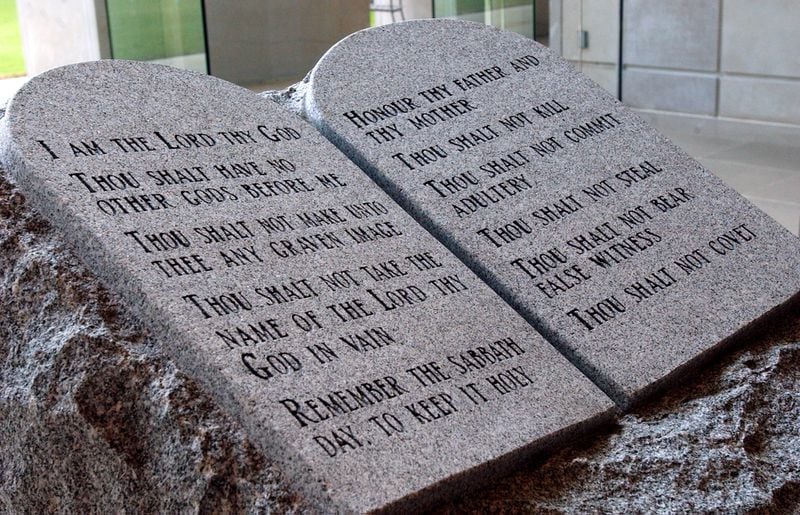

In 2003, Pryor found himself in the national spotlight for his prosecution of Alabama Chief Justice Roy Moore, who had defied a federal court order to remove a two-ton monument of the Ten Commandments from the state judicial building.

Pryor had previously supported the display of the Ten Commandments. But when Moore defied the court injunction, Pryor stepped in and tried the case against Moore in the very courtroom in which Moore had presided as chief justice.

After a trial, a special judicial disciplinary court unanimously voted to oust Moore from the bench. (Ten years later, Moore was again elected the state’s chief justice, although he’s been suspended without pay since last fall for ordering probate judges to defy federal court orders allowing same-sex marriages.)

As for his getting involved in the Ten Commandments case, Pryor told a Federalist Society panel in Florida last year, “I really never had any question about it.”

He added that if someone had told him when he finished law school that he’d return to his home state, become attorney general and persuade a court to remove the state’s chief justice from office, “I would have thought that’s a great way to end a career as a lawyer.”

But a year later, Pryor was appointed to the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta, which oversees cases from Georgia, Alabama and Florida. On the court, Pryor has been a reliable vote for prosecutors in criminal appeals, particularly those filed by inmates on Death Row. In 2009, he authored a decision upholding Georgia’s controversial voter identification law, finding that the burden on the voter of having to acquire an approved ID did not outweigh the state’s interest in safeguarding the integrity of its elections.

But Pryor’s decisions on the 11th Circuit in a few cases have upset a number of evangelicals and conservative legal groups.

Among Pryor’s most outspoken detractors is the Judicial Action Group, whose president, Phillip Jauregui, served as Roy Moore’s lawyer during the Ten Commandments case. Jauregui recently wrote that while Pryor has shown a conservative judicial philosophy in some cases, he’s exhibited “a very liberal activist judicial philosophy in others.”

‘Committed to the rule of law’

The decision mentioned most often is the case of Vandy Beth Glenn, who was fired as an editor and proofreader for the Georgia General Assembly in 2007 after she said she was going to make the transition from man to woman. Pryor joined the ruling authored by Judge Rosemary Barkett, a liberal jurist who is no longer on the court.

“An individual cannot be punished because of his or her perceived gender-nonconformity, ” said the opinion, citing a precedent set by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1989. “Because these protections are afforded to everyone, they cannot be denied to a transgender individual.”

In a decision last month, Pryor revived a lawsuit brought by a teacher who was denied an application to establish a gay-straight alliance group at a Florida middle school. He previously joined another ruling that said Augusta State University could require a graduate student to undergo a remediation plan because she’d said homosexuality was a disorder and intended to try to “convert” fellow students from being homosexual to heterosexual.

In a concurrence to the majority opinion, Pryor noted that the university had not barred the student from expressing her views and said his court didn’t need to sit as “ersatz deans and educators” and second-guess the university’s methods. “In matters of instruction and academic programs, federal judges must instead exercise restraint,” he wrote.

Anthony Kreis, a professor at the Chicago-Kent College of Law, said Pryor’s decisions in these cases shouldn’t “earn him much love from the LGBT community, given the results were compelled by precedent and clear statutory text.”

Pryor is undoubtedly a solid conservative who’s sure to draw opposition from the civil rights community if he’s nominated, Kreis said. “However, there’s little doubt that he is a judge committed to the rule of law. That’s no small point to overlook.”

WILLIAM H. PRYOR JR.

Born: April 26, 1962, in Mobile

Career: Law clerk to Judge John Minor Wisdom of the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans, 1987-88. Private attorney for two law firms, 1988-1995. Deputy Alabama attorney general, 1995-97. Alabama attorney general, 1997-2004. Judge on the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta, 2004-present.

Family: Married with two daughters.

Education: Bachelor's degree, magna cum laude, Northeast Louisiana University, 1984. Law degree, magna cum laude, Tulane University.

About the Author