For years, thousands of rape kits sat in storage at the Georgia Bureau of Investigation untouched and untested as the agency’s crime lab found itself short-staffed and unable to keep pace.

But an influx of more than $850,000 in new funding from the state to add more scientists and lab technicians has officials hopeful the agency will eventually eliminate the rape kit backlog.

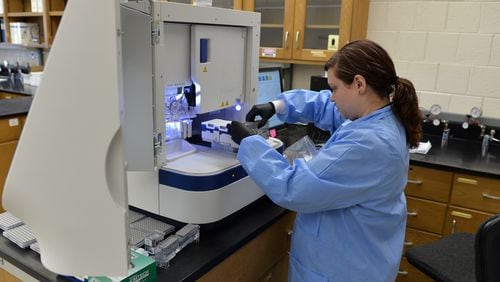

The crime lab is adding four scientists and two lab technicians to the team whose sole job is to test the DNA in backlogged sexual assault kits. The additions come as the new state budget goes into effect Saturday.

RELATED: Evidence yields DNA hits

EXCLUSIVE: DNA evidence withheld from police

And when more of those new dollars are freed up on Jan. 1, four more scientists and two more lab technicians will be added to help eliminate the backlog, which includes some kits that were collected more than 18 years ago.

All the while, hundreds of new evidence kits are coming in each month.

The state’s forensic lab gets an average of 300 new rape kits a month — taking in more than 1,650 since Jan. 1.

“We’re making progress,” said George Herrin, director of the GBI’s Division of Forensic Sciences. “It’s slow. It’s steady. We’re seeing improvement.”

Out of a $25 billion state budget, the $856,000 appropriated specifically for testing old sexual assault kits is minuscule. But it has still thrilled those who were outraged to learn about the backlog.

“The needle is moving” because of bi-partisan support for more funding, state Rep. Scott Holcomb, D-Atlanta, said of the drop in backlogged kits since the first of the year.

Before the Legislature approved the additional funding, the state was using a private lab, plus about two dozen scientists and lab technicians funded by a grant.

"We have a lot more work to do," said Holcomb, who was a House sponsor of Senate Bill 304, which set a deadline for law enforcement agencies to send in all sexual assault evidence if the victim wants their case to be prosecuted.

In January, the state crime lab had more than 9,000 kits with DNA to process, many of them years-old evidence packages that police agencies had sent because of the 2016 law. The law was pushed after more than 1,300 rape kits were found stored and forgotten at Grady Memorial Hospital and another 218 kits had been stored at Children's Healthcare of Atlanta because police agencies had not retrieved them.

The new hires will focus only on testing rape kits. The DNA unit has a staff of 50 who also analyze DNA evidence collected in all types of crimes and not just sexual assault. A private lab under contract with the GBI to process some of the older kits is also doubling its capacity to 100 kits per month.

According to the GBI, the lab now has almost 2,000 old sexual assault kits waiting to be tested in addition to 2,219 packages collected in newer, active investigations. The lab also has 1,263 sexual assault kits dating prior to 1999, when the technology for testing DNA was not available.

Of the backlogged kits, the lab has finished with 830 of them since they started sorting through the evidence in May 2016. That’s about one-third of the total that can attributed to the change in Georgia law that required law enforcement agencies statewide to send in everything they had.

Scientists found enough DNA in 161 kits to enter the results into the Combined DNA Index System, a national repository of results on samples of DNA from a known offender or biological evidence in another crime that has not been linked to a suspect. Of those, 81 matched evidence already in CODIS.

Some law enforcement agencies have had difficulty locating victims so many years after their alleged sexual assaults.

“We’re making progress,” Holcomb said. “I know the state has identified repeat offenders and it’s extremely important that we take action based on the testing and we hold those responsible for these crime accountable.”

In addition to the new scientists and technicians, the lab is also putting new processes in place in hopes of processing 300 to 400 rape kits per month.

“We are slowly increasing our capacity,” Herrin said.