Come one! Come all! You’ll be amazed and astounded by the stories of these eleven amusement parks that once called Atlanta home. Then watch them disappear before your very eyes!

The World of Sid and Marty Krofft

For a place that was only open for six months, the World of Sid and Marty Krofft made quite an impression. In 1976, the Krofft brothers were at the top of their television game, having produced trippy children’s shows like “H. R. Pufnstuf” and “Land of the Lost.” In May of that year, they created an indoor, multilevel theme park in what is the CNN Center today. The park featured a carousel, a giant pinball machine ride and general psychedelic weirdness.

Attendance was disappointing however and the park closed in November. As Actual Factual Georgia explains it, the park's demise was partly due to expensive tickets, broken rides and a general sense that downtown was too sketchy for tourists. Today you can still use the park's escalator to enter the Inside CNN Studio Tour, because why waste a good escalator?

Credit: Kenneth Walker

Credit: Kenneth Walker

Ponce de Leon Park

Credit: Special (Postcard)

Credit: Special (Postcard)

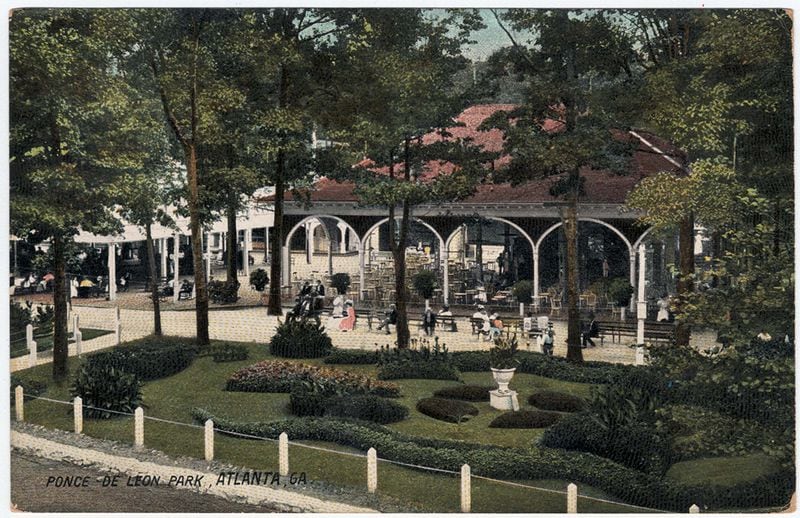

Before there was a Ponce City Market or a Sears Building, there was Ponce de Leon Amusement Park. And before the amusement park, there was Ponce Springs. Atlantans began making out-of-town excursions to visit the springs in the years following the Civil War, according to a comprehensive history of the park by Sarah Toton.

Landowner John Armistead sold the water from the spring, claiming that the waters had medicinal properties. A map from 1911 shows the original spring located below where today's Beltline walkers enter Ponce City Market. In the 1870s the Atlanta Street Railroad Company began to run a trolley service down Ponce de Leon Avenue to take visitors to the springs.

In 1887, the same street rail company purchased the land and began to turn it into an amusement park. The park officially opened in 1903 and fronted both sides on Ponce de Leon Avenue. On the north side (think Whole Foods), visitors could enjoy a lake with summer houses along — where else? — Lakeview Avenue. The south side (think Ponce City Market) was home to "the Coney Island of Atlanta," with attractions such as a dancing pavilion and skating rink, an "enchanted canal," a toboggan slide, an aerial tramway, two moving pictures galleries, a circle swing, something known as a "human roulette" and even alligator wrestling.

One thing the park did not have was African-Americans, and signs at the park entrance made it clear that segregation was enforced on the grounds. In the early 20th century, the park began to morph into other attractions. In 1907, the lake was drained to make room for the Atlanta Crackers stadium, which became the bigger draw. The amusement park land was sold to Sears-Roebuck in 1924 at a time when Ponce de Leon Avenue was becoming a buzzy place for industry, business and residences.

Credit: Unknown

Credit: Unknown

White City

Credit: Special (Postcard)

Credit: Special (Postcard)

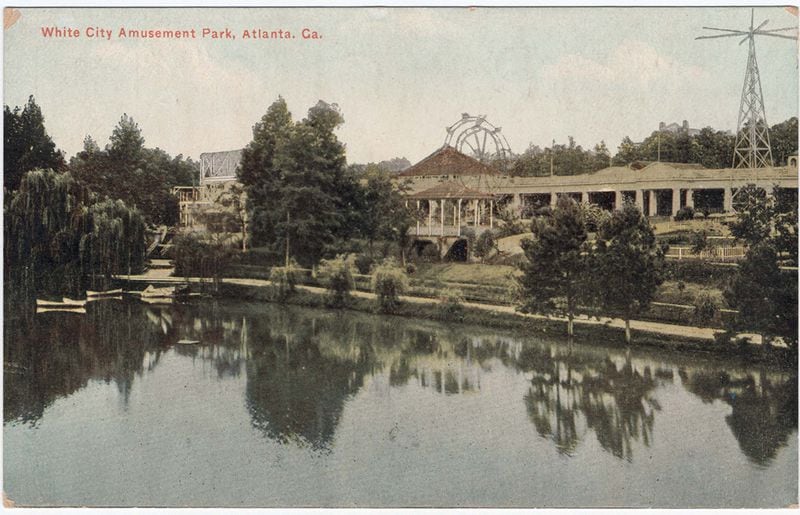

White City, which opened in 1907, will always be associated with C.L. Chosewood, one of the more colorful characters in Atlanta history. Chosewood was a city councilman whose business interests often overlapped with his public service, to put it nicely. The not-nice way to put it is that he was often accused of enriching himself while in office. Chosewood owned a sloping tract of land known as Little Switzerland, just a block east of today's Grant Park.

Back then, "White City" was a very popular name for amusement parks. The name comes from the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, which was the gold standard of expositions at the time. That fair featured a set of 14 large Neoclassical buildings that were all painted white, which spawned the nickname "White City."

Atlanta's White City featured a Ferris wheel, a circle swing, a skating rink, a swimming pool and a lake. A Sanborn Fire Insurance map from 1911 also shows a "Scenic railway 5 to 40 feet high," which sounds like a roller coaster to us. Today, hundreds of children return to the place every day for a different reason — it's the site of Parkside Elementary School. (thanks to Larry Johnson for additional research)

Lakewood Fairgrounds

Credit: AJC

Credit: AJC

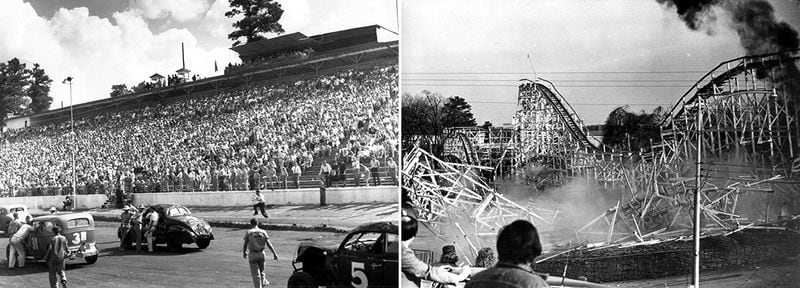

The Lakewood Fairgrounds have lived at least nine lives. The land served as Atlanta's first waterworks in 1893, then became a summer resort and music venue in 1895 before becoming the site of the Southeastern Fair from 1916-1975.

In 1917, a dirt track featured horse racing and motorcycle racing before becoming Lakewood Speedway in 1938, the largest stock car racing track in the South and a legend in its own right. But back to those fairgrounds — hands down, the most memorable part of the Midway was the Greyhound, a 2,950-foot roller coaster with a 66-foot drop. The Greyhound's last moments on earth were recorded during an explosive stunt in "Smokey and the Bandit 2."

In the 1980s the grounds were leased to the film studio Filmworks USA. The outdoor amphitheatre opened in 1988 and a popular antiques market opened the next year. In 2006, the antiques market closed in order to pave the way for another use — the EUE/ScreenGems studios, which remain there today. The fairground's four main Spanish Colonial exhibition halls still anchor the site, but expect to get turned away by security if you try to visit.

Credit: Unknown

Credit: Unknown

Credit: AJC Staff

Credit: AJC Staff

Funtown

Credit: Scuffalong on Tumblr

Credit: Scuffalong on Tumblr

Funtown was a flashpoint in the civil rights movement, but that's not how a lot of children of the 1960s remember it. For those lucky enough to see it on the inside, the park on Stewart (now Metropolitan) Avenue included rides with colorful names like the Wild Mouse roller coaster, the Crazy Daisy and Kiddie Whip. There was also a Ferris wheel, a train and a whole Midway full of unhealthy food, while a batting cage, a miniature golf course and a bowling alley offered more fun.

The park advertised heavily and promoted plenty of theme days. In 1963, however, the park became nationally famous when Martin Luther King Jr. mentioned it in his "Letter from Birmingham Jail." In the letter, King told of the pain he felt in explaining to his daughter Yolanda why she wasn't welcome at the whites-only park. This story later got retold in speeches that King gave throughout the next year.

Whether the park ever integrated is remembered differently depending on who you ask. The consensus on online forums is that the park closed rather than integrate, but one former park employee claimed in a 1981 AJC article that Martin Luther King Jr. eventually took his family on the rides. What's known for sure is that the park closed in 1967 after selling the bulk of its rides. And maybe it's just as well — Six Flags Over Georgia opened that same year.

The mini golf and bowling alley stayed open for a few more decades and the Funtown ruins took on a creepy life of their own, as nature gradually reclaimed the remaining attractions and buildings on the site. Sometime in the 1990s the bowling alley and the Funtown sign were finally gone as well.

Lion Country Safari

Wild beasts once roamed the lands where the cluster homes of Monarch Village are today. The Stockbridge community sits on Walt Stephens Road, where Lion Country Safari welcomed visitors from 1970-84.

The drive-through safari park was part of a chain with six locations. Only the West Palm Beach location still exists. Visitors could drive their cars through the park while animals such as lions, ostriches, zebras and rhinos weaved their way through the slow traffic. The park featured other animal attractions that didn't require a driver's license, such as a bird show, a parade and a few rides.

Mooney's Lake

Credit: University Of Georgia

Credit: University Of Georgia

Mooney's Lake was a Buckhead attraction back when Piedmont Road was a narrow two-lane street. The lake was off Morosgo Drive and occupied the exact spot where the I-85/GA 400 interchange is today. According to this Actual Factual Georgia feature, the summertime swimming hole was the brainchild of Deuward S. Mooney, who opened it in 1920. The park included horseback riding, canoeing, miniature golf, a zip line over the water, a children's train and a pavilion. You can watch two home movies from the mid-1950s of the park here and here. In 1958, the park closed after a fire damaged the pavilion area. The lake was filled in. The area would soon be replaced by Broadview Plaza and later Lindbergh Plaza.

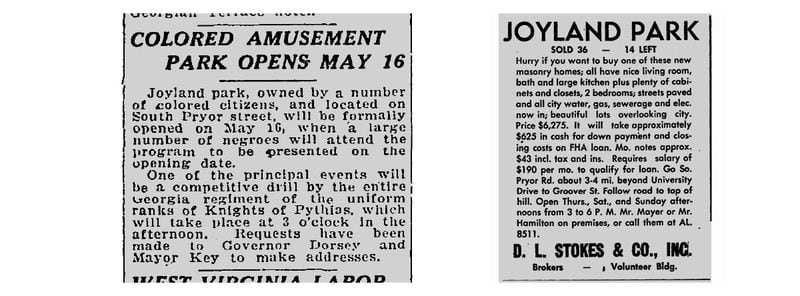

Joyland

Joyland opened in 1921 to serve African-Americans who weren't allowed in the city's segregated amusement parks. The park, on South Pryor Road only a quarter-mile north of Lakewood, started off with a bang. Its opening-day festivities, noted at the time in the Atlanta Constitution, featured triumphant speeches by African-American luminaries, as well as the Atlanta mayor himself.

One month later, the scene was more chaotic. A Constitution article describes an incident where strong winds damaged the park and a leopard briefly got loose when a tree fell on its cage. In 1926, an advertisement in the Atlanta Independent announced that the park was under new management. The grounds later turned to farmland before becoming a subdivision in 1952. That subdivision is still known today as Joyland. (thanks to Larry Johnson for additional research)

Storyland

Fairy tales and nursery rhymes were the theme of Storyland, on Highway 41 near Akers Mill Road in Marietta. Storyland opened in 1956 as part of a small chain of nursery-rhyme theme parks (the others were in Florida, New York and Cape Cod), although it featured locally crafted exhibits. According to a recent Actual Factual Georgia report on the park, children could walk a wooded trail and interact with the likes of Little Jack Horner, Humpty Dumpty, Jack & Jill, and Little Bo Peep. Some exhibits were static and some were animated.

Other celebrities dropped in from time to time too — an Atlanta Constitution article from 1966 mentions King Kong and the Great Pumpkin being in attendance. Batman and Robin paid a visit too. The park remained open until sometime in the early 1970s to the best of anyone's memory. Or was it all a dream? (Andy Johnson contributed)

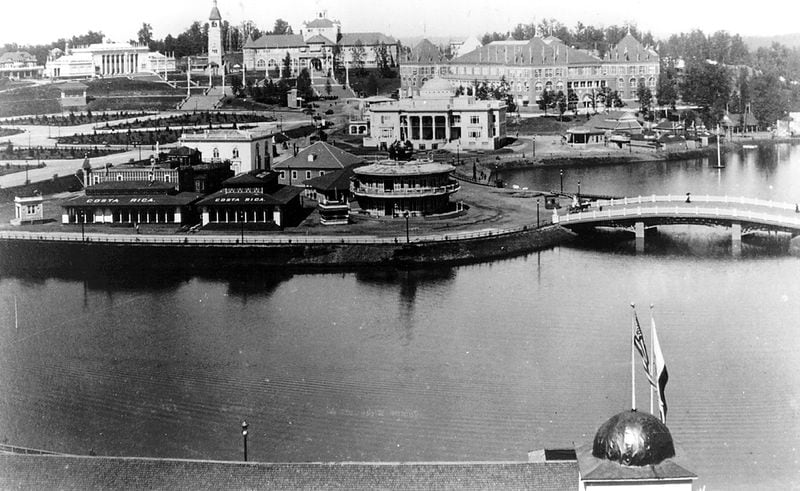

Piedmont Park

Credit: Frederick L. Howe

Credit: Frederick L. Howe

Atlanta hosted three Cotton Expositions in the 1800s. The first, the 1881 International Cotton Exposition, was held in Oglethorpe Park near today's King Plow Arts Center. The 1887 Piedmont Exposition was held in Midtown's Piedmont Park. And despite the fact that President Grover Cleveland attended that one, it's still not the one you're thinking of. You want the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition — the one with its own John Phillip Sousa march, Booker T. Washington's "Atlanta Compromise" speech, and a guest list that included Buffalo Bill and the Liberty Bell.

The exposition lasted for three months and was technically a financial disaster, but as a bit of Atlanta promotion, it got the job done. A train spur off today's Beltline took visitors and exhibit materials into the park. Visitors could disembark at a train station between the large meadow and lake Clara Meer. Oak Hill was the site of the Midway, where you could find the "Phoenix Wheel," what we would call a smaller version of the Ferris wheel, an invention only two years old at that time.

Other attractions included a "scenic railway" ride and an early moving-picture exhibit called a "Phantoscope." There was a "Shoot the Chute" too — kind of a waterslide with boat-cars — that was later used at Lakewood Park. The Buffalo Bill Wild West show was held in the large meadow at 10th and Monroe. When Buffalo Bill's show ended its run, the meadow was further used as the field for a University of Georgia-Auburn football game (Auburn won).

Credit: Pete Corson

Credit: Pete Corson

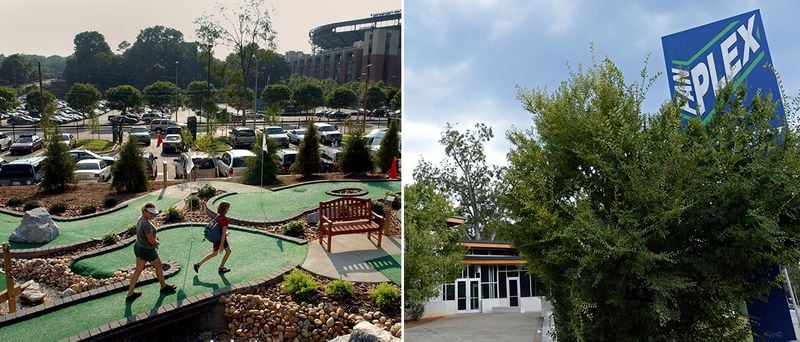

FanPlex

Credit: AJC

Credit: AJC

FanPlex has a reputation as one of the city's most notorious public projects in recent years. It barely qualifies as an amusement park, but it deserves inclusion here because its ambitions were large. Created and administered by the Atlanta-Fulton County Recreation Authority at a cost of $2.5 million, the facility included a video arcade and a miniature golf course. It occupied a building across the street from Turner Field and was intended to give Braves fans something to do in the Summerhill community before and after games. FanPlex closed in February 2004 after only 20 months in business, but its name has lived on as shorthand for "City of Atlanta boondoggle."

In the years immediately after its close, the city was unable to find a buyer that could match its $2.7 million asking price. Today, that price looks like peanuts compared to Georgia State University’s $300 million mixed-use development that’s proposed for the Turner Field site. And even though that deal does not include the FanPlex property, stay tuned. Neighborhood real estate is on the rise and FanPlex may have the last laugh yet.

Credit: AJC

Credit: AJC

About the Author