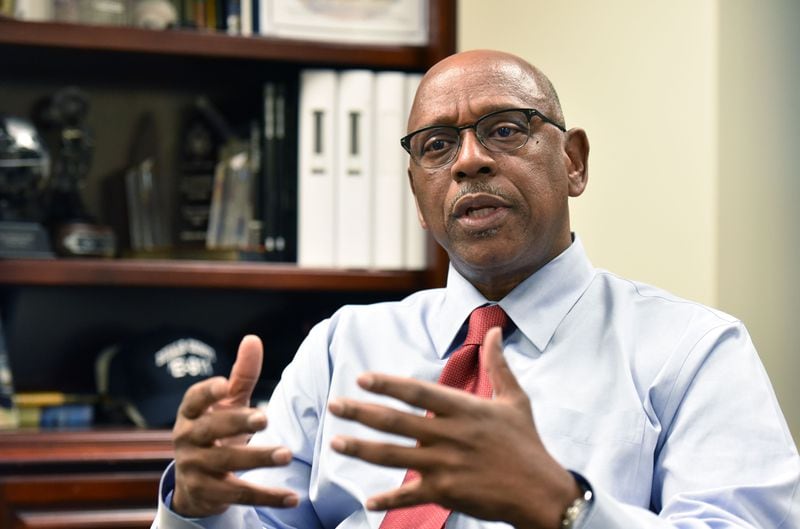

DeKalb County Public Safety Director Cedric Alexander, who became a national advocate for better policing after the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., announced Wednesday he’s resigning.

Alexander will step down this month after leading the county police force for four years, a time in which he often spoke about the need to rebuild trust with communities, even as officers in his department were involved in shootings of unarmed men.

As president of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives, Alexander traveled to Ferguson in August 2014 to defuse tensions between protesters and police. He urged police departments to improve relationships with the residents they serve and increase diversity among their ranks.

He said shootings by police officers need to be handled openly and honestly — themes that were echoed by President Barack Obama's Task Force on 21st Century Policing, which in 2015 recommended training officers on use of force and de-escalation techniques. Alexander was a member of the task force.

Alexander said he emphasized accountability and professionalism.

“I made it very clear to this community — we were going to be honest, we were going to be forthright and we weren’t going to lie to them,” Alexander said. “If we did things wrong, we were going to own it and we were going to fix it.”

Alexander said he’s retiring from his 40-year career in law enforcement, but he’ll continue working as an analyst for CNN.

Alexander was hired as DeKalb's police chief in April 2013 and became the county's public safety director in February 2014, overseeing police, fire, 911 and emergency services.

He was a finalist for the Chicago police superintendent job last year, but Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel instead chose Eddie Johnson, who was the city police department's chief of patrol.

Alexander, who holds a doctorate in clinical psychology, understood the need to empathize with victims and pressure law enforcement agencies to change the way they operate, said Laurie Robinson, a co-chair of the Task Force on 21st Century Policing.

“He has a probing mind, and he’s always focused on exploring how we get to the truth, how we move forward, how we come to a better understanding and come together across divides,” said Robinson, a professor of criminology, law and society at George Mason University.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Back in DeKalb, Alexander dealt with local shootings by police, low morale and elevated crime rates in some areas.

A grand jury brought charges against Officer Robert Olsen, who allegedly shot and killed Anthony Hill, an unarmed and naked man who suffered from bipolar disorder.

In another case, Kevin Davis was shot in his apartment after he called 911 for help when his girlfriend was stabbed by a roommate. A grand jury recommended no charges against Officer Joseph Pitts, who said he twice ordered Davis to drop a firearm.

Alexander was a leader in the much-needed national discussion about shootings involving police, said DeKalb Commissioner Greg Adams, a former police officer.

“He didn’t just focus on the needs of DeKalb County. He focused on the needs of other states as well,” Adams said. “That stood out really well to me because he didn’t have to get involved in the Michael Brown situation, but he did.”

Alexander published a book last year, “The New Guardians: Policing in America’s Communities For the 21st Century,” that emphasized community policing, where cops work their beats as trusted guardians instead of crusading warriors.

He announced his resignation a day after the DeKalb Commission rejected pay raises for police and firefighters in the county's annual budget.

Jeff Wiggs, president of the DeKalb Fraternal Order of Police, said he hopes the public safety director position is abolished so its $176,800 salary can go toward officer salaries.

The special grand jury report in 2013 said the public safety director job created "unnecessary tension and bureaucracy" that introduced political interference to policing.

“We wish him the best, however with our financial situation in the county, I hope they will revert back to abolishing the position,” Wiggs said. “We’re in a crisis here in public safety.”

The number of DeKalb officers has dropped to 733 from a high of more than 1,100 several years ago. Some officers left for better-paying jurisdictions, and the department shrank when the young cities of Brookhaven and Dunwoody started their own police forces.

Crime rates for some violent crimes — rapes, home burglaries, pedestrian robberies — declined last year, but homicides increased by 14 percent.

DeKalb CEO Mike Thurmond said the position will remain vacant for now, and perhaps permanently. He’ll talk with county commissioners and community leaders before making a decision.

“Dr. Alexander did an excellent job leading public safety,” Thurmond said. “He stabilized the situation.”

DeKalb Commissioner Kathie Gannon said she hopes Thurmond retains the public safety director position. The director could help coordinate efforts to increase pay and retention rates across police, fire and other departments.

“(Alexander) helped our community become closer to our public safety officers,” Gannon said. “If we say public safety is a priority, that’s what we have to do, and something else has to get cut.”