The federal bribery investigation hanging over Atlanta City Hall has extracted pledges for a more transparent and open government from candidates still in the race to succeed Kasim Reed and become the city’s 60th mayor.

With less than two weeks until the Dec. 5 runoff election, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution dissected spending reports from Keisha Lance Bottoms and Mary Norwood to see how transparently each ran their campaign operations and complied with Georgia’s campaign finance laws over the past year.

The AJC analysis found serious omissions in Bottoms’ reports, prompting a promise from the candidate to correct them, and raised questions about Norwood’s employment of city council staff on her campaign.

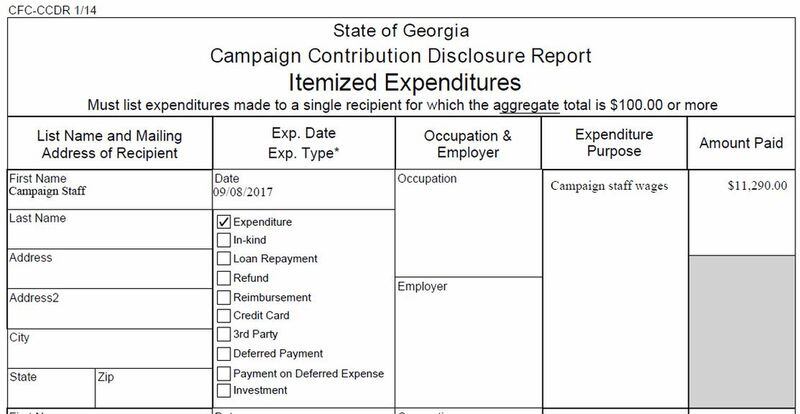

Bottoms’ reports provide no transparency in any of the 38 entries that spent a collective $182,000 on campaign workers. No individual names were listed on expenditures, as is required by law. Instead, the reports say “campaign staff” in the space where individual names are supposed to be disclosed.

A few of the entries say “wages” in the space that requires a reason for the spending; most are left blank.

Stefan Ritter, executive director of the state ethics commission, said his agency had previously identified the lack of itemization in Bottom’s campaign finance reports. The commission “is investigating it and cannot comment further,” Ritter said.

Bottoms called the omissions from Jan. 16 to Oct. 20 "bookkeeping errors."

“We keep very meticulous records,” she said.

Norwood’s disclosures list the names of dozens of individuals — including two people from her city council office — who were paid for work ranging from canvassing neighborhoods to cold-calling potential voters. Each of the entries on her disclosures list the amounts paid to the individuals.

Rick Thompson, former head of the state ethics commission, said documenting the name and address of everyone who receives payments of more than $100 is clearly spelled out in the law.

The same rule applies to donations of more than $100, which also were not well-documented by Bottoms' campaign, according to a previous AJC analysis.

“It’s very important that everyone knows where the money is coming from and how it is being spent,” Thompson said. “The public has a right to know … before they go to the polls. It can help voters make up their minds: who is supporting the candidates and who are they paying?”

Bottoms said Wednesday that one of her council aides took unpaid leave from the city to work on her campaign, a move that eliminates any question about whether a campaign staffer is doing political work on the taxpayers’ dime.

Councilman Howard Shook said he also had a council staffer take leave so she could work on his council re-election campaign this year. He did so “in an abundance of caution.”

“I just didn’t want anyone, right or wrong, to even be able to raise the issue,” Shook said.

Norwood defended her campaign's use of actively-employed council staff, saying: "They know all of our constituents — they know when someone calls whether it's a campaign issue or a city issue."

In total, Norwood’s reports document more than 206 individual payments to campaign staffers for a combined $301,000 — an average of $1,461 per expenditure, the AJC’s analysis found.

Some of Bottoms’ spending not fully disclosed

Bottoms is an attorney who has run two successful campaigns for Atlanta City Council. She has called for an audit of the city’s procurement process and said all elected officials should make public their tax returns.

But last week, after Norwood released nine years of her tax returns, Bottoms was unclear about if and when she would release her own returns. Her campaign did not respond to a message Wednesday about the issue.

State law requires that political candidates disclose names, address and occupations of all people who give to or receive payments from their campaigns in excess of $100.

Metropolitan elections in many cities, including Atlanta, are notorious for large, last-minute spending of get-out-the-vote money — cash payments to individuals who help round up registered voters and get them to the polls on election day.

The law’s requirement to clearly identify recipients is intended to bring accountability and transparency to campaign operations.

Only two of the 38 payments to “staff” in Bottoms’ disclosures fall below the $100 threshold and weren’t required to be detailed, according to her reports. The payments average about $4,800.

The largest staff payment from Bottoms’ campaign was $28,615, made just one month before the general election. The second-largest payment came 14 days later, on Oct. 20, for $25,650.

An additional seven payments, each more than $6,000, were made between July 1 and Sept. 22, according to Bottoms’ disclosure reports. None provide any information about who or how many people were paid. The reason given for each is “wages.”

“That’s not good at all,” Thompson said. “That … should be a big deal to the ethics commission.”

The lack of disclosure makes it impossible to discern about 14 percent of Bottoms’ campaign spending through the last filing on Nov. 1, according to the AJC’s analysis. Campaigns can be fined up to $1,000 per violation in such instances, according to the law.

Bottoms said she only learned of the failure to disclose when an AJC reporter asked her about it during an Nov. 16 interview. She promised to amend the reports by adding the information.

“That’s a bookkeeping error in terms of how we categorize it,” Bottoms said. “We keep very meticulous records in terms of who’s paid what. If that’s an error, then it’s just a matter of amending the report and making sure it’s itemized.”

Bottoms sent a text Wednesday to the AJC saying her campaign was still in the process of amending the reports to add the missing information. She did not respond to a question about when the amendments would be filed.

Donors lack detail, too

A previous AJC and Georgia News Lab report found that Bottoms' campaign also had disclosure problems with donors: employers of more than 20 percent of her campaign's contributors were not identified.

The omissions dated to Bottoms’ earliest disclosure reports and continued with each subsequent filing. A notation of ‘information requested’ appeared on some of those entries, but subsequent amendments have not filled in the missing information.

The lack of employer information hindered an AJC analysis of contributions made by city contractors to the nine major mayoral candidates in the general election.

Bottoms’ campaign received 65 percent of donations made to the nine candidates from people and companies expressing interest in the airport retail contracts, which are collectively worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

The airport contracts became a major campaign issue when Reed pushed to have them awarded before the end of his term, despite the fact that they don’t expire until September 2018.

Contributions to Bottoms’ campaign from that group amounted to $187,000, and included $33,600 from people associated with the PRAD Group — an airport contractor raided by the FBI in September, apparently in connection with the bribery investigation.

Bottoms' campaign returned $25,700 of those donations, according to her November campaign expenditure report.

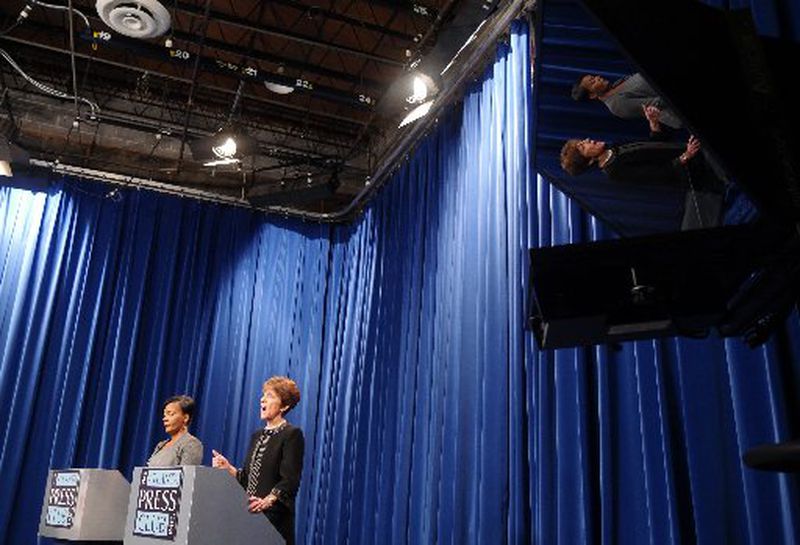

Credit: Hyosub Shin

Credit: Hyosub Shin

Norwood defends use of city staff

Norwood, a three-term councilwoman, lost a squeaker of a runoff to Reed in the 2009 mayoral election. She now faces Bottoms, a council colleague who Reed has endorsed with bare-knuckle politics for most of the year.

Norwood says she wants to place all government spending online and hire an independent person to oversee city purchasing.

A long-time Buckhead resident, Norwood raised significantly more money than Bottoms and spent more on her campaign’s staff, according to the disclosures.

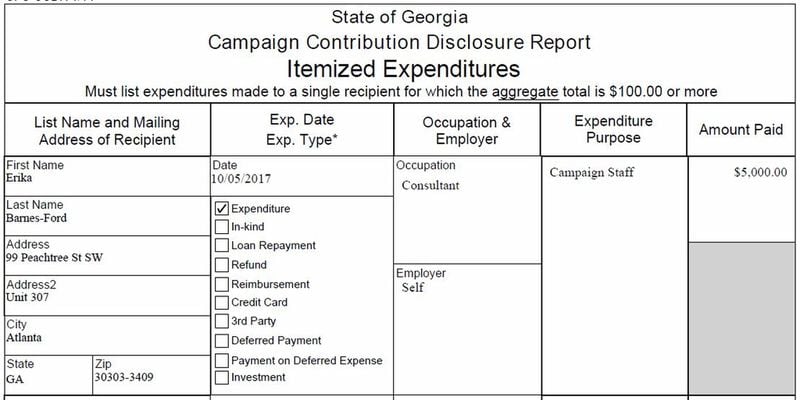

Norwood’s disclosures document payments to more than three dozen individuals, with the vast majority of that work for neighborhood canvassing or phone banks. Of the campaign’s 206 payments to staff, 122 were for less than $1,000. The largest was for $5,000, of which 18 such payments were made.

Several of those $5,000 payments went to Erika Barnes-Ford, Norwood’s campaign manager who is her chief of staff at City Hall. In total, Barnes-Ford was paid $31,500 from January through Oct. 5, although some of that money included reimbursement for campaign expenses.

Norwood said her council staff doesn’t work conventional hours, often answering emails early in the morning and attending functions late in the evening. She said because of that, it is appropriate for them to sometimes work on her campaign during the day — so long as they differentiate their hours worked for each.

“There is no 9-to-5 on my (city) staff,” Norwood said. “If it was, then they wouldn’t get half the work done because that’s not when the community needs us. The community needs us at a 7-to-9:30 night meeting.”

When asked how she differentiates her time on the different jobs, Barnes-Ford showed the AJC a hand-written journal that had hours written down dating back to January. She said city time is highlighted in yellow, campaign hours highlighted in red.

“I keep it hand-written, and on my Google calendar,” Barnes-Ford said. “So that is my methodology.”

Anthony Benton, Norwood’s constituent liaison at city hall, was paid $46,000 by the campaign to direct its field operations. He uses a similar method to keep track of his time.

Thompson said he thinks it’s an appropriate method, although he said the better way to handle those situations would be to have city employees take leave while working for the campaign, as Bottoms has done.

“Unlike the federal level, there’s no formalized way in the state of Georgia to distinguish the difference between working on government time and working on your personal time,” Thompson said. “A journal seems to be good … I think that’s fine.”

Other campaign spending

Other spending by the campaigns is also revealing.

Norwood is a self-described independent who has fended off charges that she is Republican. But she has employed two high-profile consultants who previously worked on the campaigns of Republican U.S. Senators David Purdue and Johnny Isakson.

Norwood also paid $51,000 to a printing company, Tucker Castleberry, that was included in a 2009 audit of City Council expenses. The audit suggested that Norwood may have hired Castleberry in violation of procurement codes, which required competitive bidding for expenditures of more than $20,000.

At the time, Norwood said the payments to Castleberry were not violations because they were made over multiple fiscal years.

Meanwhile, Bottoms has paid $23,660 to a company she listed as GA. P. Management, according to her disclosures. The AJC identified the company as Georgia Project Management and Design. The company is not registered with the state, but is owned by Clayton County businessman Robert Walker, who has been a vendor for the city of Atlanta.

Bottoms said she paid Walker’s company for yard signs.

In 2014, Georgia Project Management was paid nearly $600,000 for snow removal by contractor Elvin "E.R." Mitchell Jr., who has pleaded guilty and been sentenced to federal prison for bribery in the City Hall case. The AJC identified $5.3 million that the city paid Mitchell's company that year for emergency snow removal, around the time he admitted to paying some of the bribes. Walker's company has not been implicated in the federal investigation.

Bottoms also paid attorney Alvin Kendall for signs, magnets and printing, according to her reports. Kendall is Walker’s attorney.

The Norwood and Bottoms campaigns must file one more campaign disclosure before the election. All candidates in the race have to file a final report by Dec. 31.

AJC reporter J. Scott Trubey and Harrison Young and Jenna Eason, reporters with the Georgia News Lab, contributed to this report.