Atlanta Public Schools is dealing with another cheating investigation. A quarter of the police officers in the district’s recently sworn-in force admitted receiving answers on a state-administered test.

Disciplinary proceedings are coming for at least 18 employees. One dispatcher allegedly fed answers to 17 officers while they took the open-book, 30-question, multiple-choice exam.

Police Chief Ronald Applin said punishment could range from a written reprimand to dismissal.

APS also sent findings of an investigation it authorized to the Fulton County District Attorney’s Office, which would determine if the cheating should be prosecuted as a crime.

“Integrity is what we’re all about. We want to make sure … that we can be trusted,” Applin said. “When you betray that trust it makes things difficult all the way around. Our officers are good officers who made some bad decisions.”

Atlanta school officials have assured the public in recent years they are working to change the culture that fostered a cheating conspiracy in which teachers corrected student answers on standardized tests. Eleven APS teachers and administrators were convicted of racketeering in 2015 in a trial that drew national attention to the roughly 50,000-student district.

Applin said that history prompted him to be "as transparent as possible" after a WSB-TV reporter, acting on a tip, inquired about allegations of police officers cheating on a state test officers must pass to access a computer network of criminal databases.

Every two years, users of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation-managed Criminal Justice Information System must be trained and tested on how to appropriately access data. The system provides millions of confidential records — including criminal history records from the FBI and other states as well as motor vehicle and driver’s license information.

In October, Applin asked an outside law enforcement agency, which he would not name, to investigate. A week ago, he received the initial findings of that investigation, based on interviews with 48 employees. Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard, Jr. reported his office received a summary of the investigation Thursday.

An investigator found problems including 17 officers who admitted receiving test answers. Applin said officers didn’t receive help with every question, just those they had trouble with.

“When officers called into the dispatch center requesting assistance with locating answers, a dispatcher provided significant assistance with locating answers and/or providing answers to officers while they were taking the exam,” stated an investigative summary APS provided.

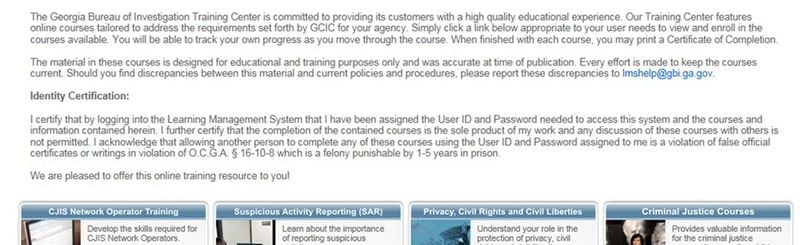

The exam lets test-takers go back to reference material while answering questions. But they must certify that the work is their “sole product” and “any discussion of these courses with others is not permitted.”

The same paragraph also states the test-taker acknowledges that “allowing another person to complete any of these courses using the user ID and password assigned to me is a violation of false official certificates or writings” — a felony punishable by up to five years in prison.

Applin said he’s unsure if what the officers admit is illegal. He interprets the language as saying it would be a “problem” if someone allowed another person to log in using his or her username to complete the test.

GBI director director Vernon Keenan said, “The officers or anyone else who is taking the training must certify that they have done the training; and they have not circumvented any of the safeguards which are in the testing process, that they have not shared answers, (that) they have completed the test as it is designed.” he said. “And if that did not occur, and they certify that they did the test themselves, then that is a crime.”

Keenan said he cannot comment on the specifics of the APS situation but reporting the findings to the district attorney to determine if a crime took place should be standard procedure.

The school district, in a written statement, said its police department “has followed and will continue to follow all appropriate protocols and procedures in this case and will proceed based on the guidance of the district attorney.”

Howard, in a written statement, said he expects his office to determine within 60 days if it should investigate the matter or refer it “for conclusion by some other process.”

Superintendent Meria Carstarphen, hired in 2014 to turn around APS after the teacher cheating scandal, declined through a district spokesman to comment.

Carstarphen will make final disciplinary decisions, said spokesman Ian Smith, and “she feels it wouldn’t be appropriate” to discuss the investigation before then.

Carstarphen and the school board backed creating a new APS police force to replace Atlanta Police Department officers who once patrolled schools. A spokeswoman for Mayor Kasim Reed at the time called that "a terrible decision."

The district's new officers took over in July of 2016. There are 66 officers on the force. All are still on the job as some await a disciplinary process the chief said would be "fair and just."

The network only can be used for law enforcement purposes. It’s a criminal offense to use it in other ways, like such as running a background check for a family member.

“It is very important that the person master the material because the consequences of misusing the information are very serious,” Keenan said.

The chief said he’s seen no indication that anyone on his command staff knew about the cheating.

“If I had, we would have dealt with this a long time ago,” he said.

APS police cheating investigation

Officers in the school district’s recently formed police department told an investigator they received help on a law enforcement exam they must pass to use a computer network that includes state and federal criminal databases and other information such as motor vehicle and driver’s license records.

The findings include:

17 officers admitted receiving test answers from a dispatcher, including 4 officers who said they also worked with a fellow officer to complete the exam

1 dispatcher admitted providing answers to officers

1 officer stated she didn’t take the exam, although her name was listed as completing the test

1 officer admitted receiving significant help with locating answers but not the answers themselves

Source: Investigative summary provided by Atlanta Public Schools

In other Education news: