Jimmy Carter said Thursday that he hoped President Donald Trump’s words and actions would “reinvigorate” the women’s movement in this country.

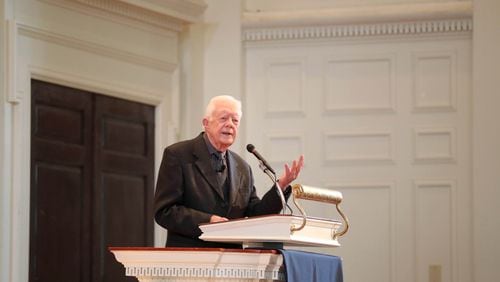

“Primarily because of President Trump’s own past record and also what he had to say about Bill O’Reilly yesterday, that he was a good guy,” Carter told a large audience at Glenn Memorial Auditorium at Emory University. “I hope that the women’s movement would be invigorated.”

Carter’s remark came during a question-and-answer session that followed his delivery of the Centennial David J. Bederman Lecture at Emory University School of Law. Asked by a staff member of student newspaper the Emory Wheel what he thought the future of Black Lives Matter and the women’s movement was under the current administration, Carter didn’t hold back. After referencing Trump’s defense of Fox News host O’Reilly against sexual harrassment claims, the former president moved on to criticize the current Justice Department for having “abandoned” efforts to improve local police departments in the area of civil rights.

“I don’t see any glimmer of hope within the administration itself, “ Carter told about 1000 people. “But I hope Black Lives Matter efforts will continue and be enhanced and I hope the women’s rights movement will continue and be enhanced.”

Carter was clearly trying not to dwell too much on politics during his speech, the theme of which was “Human Rights in Today’s World.” Several times, as when he talked about the ongoing situation in Syria, he prefaced his remarks with “I’m not going to say too much” about the current president or his administration’s policies.

RELATED VIDEO:

But he couldn’t censor himself entirely, saying that the U.S’s championing of human rights and international law has weakened in the last few years, a trend that’s intensifying now.

“The debate in the last two to three days, Syria is still at the forefont, with, I would say, Russia and Iran basically supporting (President Bashar) Assad and the U.S. on the other side,” said Carter, who didn’t go into specifics of what he thought Trump would do about the chemical bombing earlier this week of a Syrian rebel stronghold. “We’ve seen in (Trump’s) campaign, he promised that in effect human rights as a standard or commitment of U.S. (policy) would be no longer applicable. I was at his inauguration and I flinched a little bit when he said the American way of life would no longer be forced on other people. I interpreted that as meaning human rights.”

If the tone of Carter's speech was somewhat pessimistic, no one should have been surprised at its theme. Carter, 92, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002 for "his decades of untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights. And he hasn't let up, not even when it's meant wading into such controversial issues as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or then-presidential candidate Donald Trump's comments about Muslims and Mexican immigrants.

Carter had campaigned for the presidency on bringing a new focus to U.S. foreign policy, one that emphasize human rights. In a March 1977 speech to the United Nations General Assembly two months after he took office, he said that the United States had a "historical birthright" to be associated with human rights.

And not just his country's birthright. In an interview with the AJC a few days before he celebrated his 90th birthday on Oct. 1, 2014, Carter suggested that his upbringing in tiny Plains, Ga., had awakened him at a young age to life's inequities and the importance of treating all people with fairness and dignity.

“There are two basic things that I attribute to myself somewhat proudly: One is human rights and the other is (working for) peace,” said Carter, who moved with his family at age four to a farm in the Archery community just outside of Plains, where most of his friends were African American. “I’d say my total commitment to human rights came from my experiences living among African-American families and seeing the ravages of segregation.”

Being a human rights advocate isn’t for everyone, Carter said.

“If you run for office to be a champion for human rights, it may not be the most popular thing you do,” he quipped.

And right now in this country, he suggested, it may be a matter of playing the long game.

“The will of the American people now is kind of America First and let’s not impose our commitment to human rights on other people, which I think is a tragedy,” Carter said near the end of his speech. “But I don’t see how to change it with the current administration in Washington.”