In all of the ways that he has been saluted this week — as a fighter, political figure, a cultural and social icon and global brand — more than 1,000 people gathered Thursday night at the Atlanta Masjid of Al-Islam to salute "Muhammad Ali, the Muslim," perhaps the one title that superseded all others and defined him the most.

“He was a Muslim and an athletic phenom,” said Imam Ibrahim Pasha, the former imam of the Atlanta Masjid.

Borrowing parts of Ali’s most famous quote, Pasha riffed off butterflies and bees.

“He stung racism. He stung Jim Crow. He stung hatred. He stung gladiators,” Pasha said. “But like the bee, he made more honey than the use of the sting.”

Ali, the three-time heavyweight champion of the world, who transitioned from fighter to moral leader when he defied the U.S. government and refused to go fight in Vietnam, died late Friday of Parkinson's disease.

"His physical ability defined him as an athlete," said Ron Thomas, sports journalism director at Morehouse College, who covered Ali. "But his uniqueness as a figure was brought out more by his choice of religion. His style and boasting set him apart in a society where black athletes were supposed to be humble. But for him to have the nerve to change his religion and name, and be willing to accept scorn and to not go to the Army and face vilification, was remarkable."

A large memorial service will be held on Friday in Ali’s hometown of Louisville, Ky.

That service will no doubt be larger than Thursday’s Atlanta service, known as Janazah. Still, the Masjid was packed.

The prayer room was set up with chairs like an auditorium. But men and women — young and old, black and white, Muslims, Christians and Jews — who couldn’t find seats still sat barefoot on the floor along the sides of the hall.

And it was fitting. Ali had several deep connections to Atlanta. In 1996, Ali lit the Olympic torch, creating perhaps the most iconic non-athletic image of any Olympic games. But 26 years earlier, it was in Atlanta that Ali made his return to the ring after his three-year ban.

When he visited Atlanta, Ali often worshipped at the Atlanta Masjid.

“The diversity of the crowd showed he was admired universally,” said Edward Ahmed Mitchell, executive director of CAIR-Georgia. “He was a Muslim and an African-American who was loved by so many, and the diversity of this evening proves that.”

Mitchell, who oversaw the ceremony, said Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed did not attend the Thursday service in Atlanta because he was traveling to Louisville.

Reed is a devoted fan of Ali’s, as much for what he did outside the ring as in it. But for many people, that is the standard reaction to Ali.

“I have been consumed over the last few days with Muhammad Ali,” said Soumaya Khalifa, executive director of the Islamic Speakers Bureau of Atlanta, who fought back tears. “When I watch videos of him, he is like a dear and near family member that I had never met. He exemplifies what a Muslim should be like — strong, courageous, compassionate, and knows himself well and was willing to pay the price for that courage.”

What is a Muslim?

Ali converted from Christianity to Islam in 1964, first as a member of the Nation of Islam before easing into conventional Islam. Along with changing his name from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali, he noted that Islam was a religion of peace when he refused to be inducted into the United States Army in 1967.

The Rev. Gerald Durley, who met Ali in 1960 on the campus of Tennessee State University just after he won a gold medal in the Rome Olympics, said that many people were confused when the champion converted.

“When we were all in our 20s, we all asked, ‘What is a Muslim?” Durley said. “But he was a man of the universe. A man of all seasons. Believe this or not, his shadow could change you. He knew who he was and he didn’t try to tell you who you were.”

He evolved, he grew

Ali’s refusal to join the Army split the country against him, nearly landed him in jail, and cost him his championship belt and three years out of the prime of his career. But as much as Ali changed over his life, Islam was a constant.

It was Ali in 2001, after the Sept. 11 attacks, who condemned the violence while again stressing that Islam was a religion of peace.

State Sen. Vincent Fort, D-Atlanta, said Ali, along with Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., was one of the three most influential black men in history, partly because of his ability to change, adapt and transform himself.

“You can see how he evolved and how he grew,” Fort said. “That is the challenge now. That we use his life and passing to reform ourselves and change this society.”

The greatest comes alive

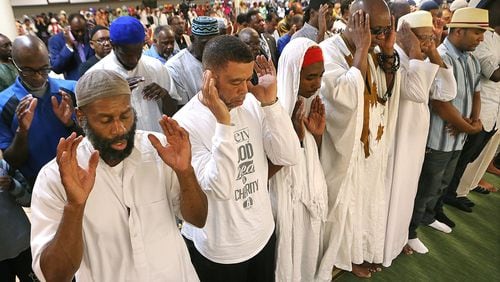

When all of the speakers were done, worshippers lined up to recite the Janazah prayers — men on one side of the room, women on the other, in accordance with Islamic rules. The middle of the room was left empty, as they all repeated four recitations of “Allahu Akbar” or “God is Great.”

At the end of the prayers, everyone mingled, filling the empty space. Some retreated in prayer and continued to observe the third day of Ramadan. Children ran around, skipping along the lines that demarcate the prayer rug.

“This is a moment when the greatest comes alive. It is not to mourn, but to celebrate,” Durley said. “We ought to be dancing up and down the street because Ali stood for justice.”