Back in September, Sean Ramsey stood at the intersection of Central Avenue and Memorial Drive just outside Atlanta Municipal Court holding a sign that read “homeless please help.”

For all practical purposes, the 48-year-old may as well have been standing at the corner of Callousness and Indifference.

Both were apparently at play when Ramsey was arrested, hauled off to jail and made to sit there 71 days without so much as a court date because he couldn’t afford to pay $200 bail.

If that doesn’t make you wanna holla, I don’t know what will. But here’s the thing that’s really needling me and ought to move you as well.

Ramsey is one of countless poor people who are treated this way and just one example of why Jonathan Rapping, a legal defense advocate and winner of the 2014 MacArthur Foundation “genius grant,” gets up every day.

Rapping realized years ago that if po’ folk like Ramsey are broke and broken, they don’t stand a chance against an equally broken system that operates like Goliath.

Rapping had ended a decade-long career as a public defender in Washington, D.C., when he first got a glimpse of how broken court systems are in our state.

It was 2004 and he’d just been invited to Georgia to become the first training director for the state’s public defender system.

It looked nothing like his D.C. office, where the caseloads were manageable and clients got the same kind of representation you’d want for a loved one.

“It never occurred to me how great the gap was between what I experienced in D.C. and what public defenders had to deal with elsewhere,” Rapping recalled.

Once in Georgia he started to see young lawyers with the same passion as his colleagues in Washington, who were just as smart and talented but were working in systems that, when it came to representing folks like Ramsey, had very low standards.

“The system would grind people up,” he said.

It was so bad, they’d either quit or become resigned to the status quo, in which case they’d start to become part of the problem.

“Against the pressure to process, you can come to abandon your ideals, and that’s what I was seeing with these young lawyers,” he said.

He came to Georgia thinking the focus of a training director was to teach law and skills, but he soon realized that wasn’t the greatest problem. What was needed more than anything was helping attorneys resist the pressure to adapt to the status quo.

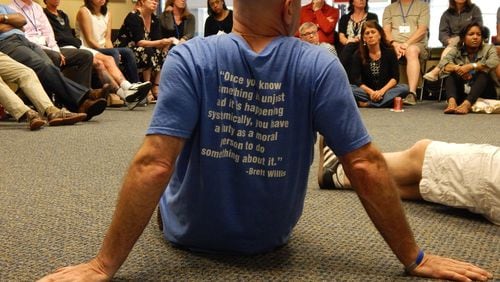

“I realized it wasn’t enough to teach people to be good lawyers in broken systems. What we really had to do was build an army of change agents to resist those systems and be at the forefront of transforming them.”

That was Rapping’s first “aha moment.”

After about two years in Georgia, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, some friends of his took on the challenge of rebuilding public defense in New Orleans and invited him to join them.

He did that for a year, leaving his wife and 3-year-old daughter to drive to New Orleans every Sunday evening and return home to Atlanta each Friday night.

He also had a chance to spend some time in Mississippi and Alabama and saw that what was happening in Georgia and Louisiana was happening there, too.

RELATED: Black men and the new Jim Crow

It became apparent to Rapping that what he’d experienced in D.C. was not the norm. It was the exception.

And so it hit him. To truly transform our criminal justice system, we would have to tackle a cultural challenge. In overwhelmed systems moving cases quickly and cheaply could become mistaken for justice. And in systems where judges appointed public defenders, or could otherwise interfere with their independence, lawyers often were more concerned with upsetting the judge than providing clients with the best representation.

He recalled watching men in orange jumpsuits lined up and shackled together in a New Orleans courtroom.

“A judge would call out a name. A lawyer would speak up but never stood near any of the men in orange jumpsuits. The case would be resolved in seconds before the judge would call another name,” said Rapping. “This processing went on until a name was called and no lawyer responded.”

The judge would call a defendant’s name and ask where he lawyer was, said Rapping.

I haven't seen one since I was locked up, was a common refrain.

Some men had been locked up for 70 days. The judge would thank him and move on to the next case.

What struck Rapping, other than the fact that a man had been locked up 70 days without a lawyer, is that no one was fazed.

“It had come to be the accepted culture, the normalized standard of justice for the poor,” he said.

If you’ve suddenly remembered poor Sean Ramsey, I hope you’re outraged because that’s exactly what would be stirring inside those of us if we watched our brother or sister or child treated this way.

How is it then we can become conditioned to watch what happens to somebody else’s father, brother, sister and not feel anything?

Rapping’s outrage motivated him to tackle the problem. In 2007, he applied for and received a $150,000 fellowship from the Open Society Foundation. With his wife Ilham Askia, a school teacher, he started building the Southern Public Defender Training Center out of their Atlanta living room.

Within the year, Askia had quit her job in the classroom and joined her husband. Together they built an army of advocates to awaken us from our slumber, to remind us that people being processed through our court system like poor Sean Ramsey are human beings. Not case files.