(This story was originally published Feb. 28, 1982 by The Atlanta Constitution)

Wayne B. Williams, a 23-year-old aspiring musical talent scout, was convicted Saturday of murdering Nathaniel Cater and Jimmy Ray Payne.

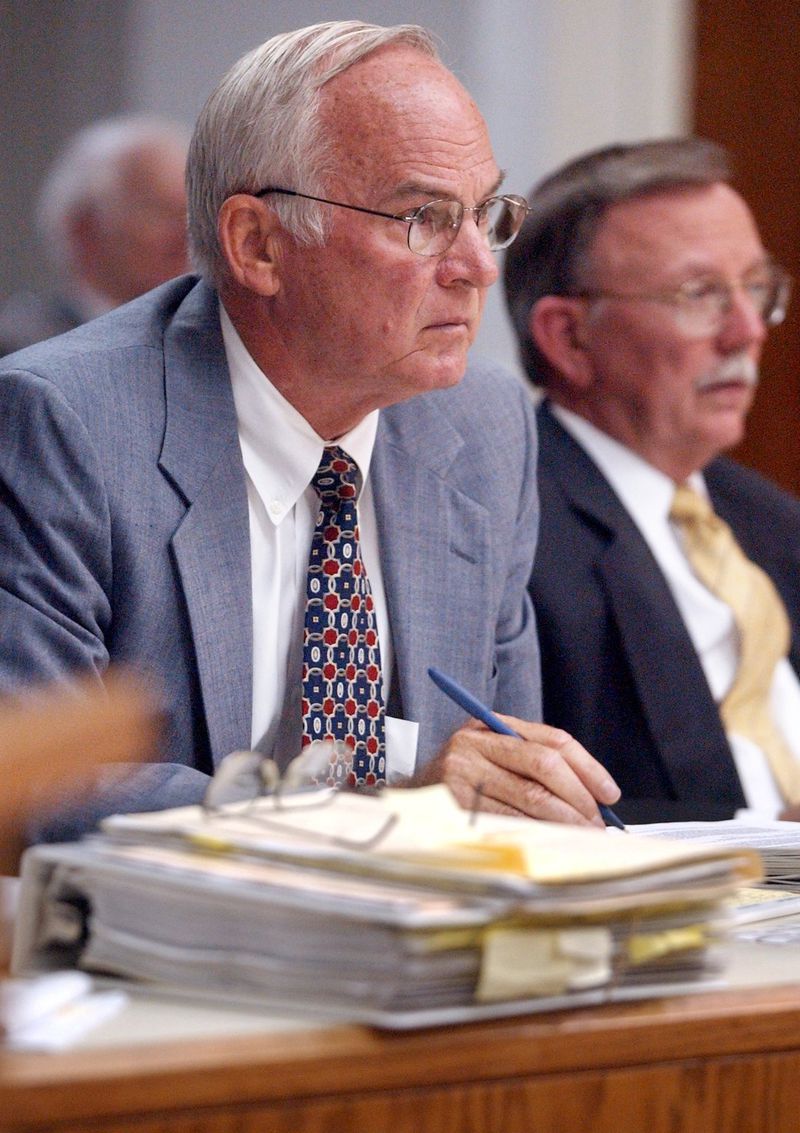

Fulton County Superior Court Judge Clarence cooper immediately sentenced Williams to two consecutive live prison terms.

After the guilty verdicts were announced, Williams and his father addressed the court. Williams, dressed in a brown suit and an open-necked shirt, instead he is innocent.

“I maintained all along through this trial my innocence, and I still say so today,” he said. “I hold no malice toward the jury, the prosecutors or the court. I hope the person or persons who committed these crimes can be brought to justice. I did not do this.

“I, more than anyone else, wanted to see this terror ended, but I did not do it,” Williams concluded. Cooper then announced his sentence. Williams will be eligible for parole in seven years.

Williams’ father, Homer Williams, also addressed Cooper before his son was sentenced. “Justice has not been one,” said. “I don’t see how anybody could find my son guilty of anything. It is not right. I just don’t see it.

“It is an injustice for you to find a young man like this guilty. Nobody has brought any evidence to prove my son is guilty,” the elder Williams said.

Wayne Williams was “calm” when he arrived back at the county jail at about 7:30 p.m. Saturday, according to a jail official. He had eaten before he got there and was taken straight to his cell.

Payne, 21, and Cater, 27, were among the last of 28 young Atlanta blacks whose mysterious deaths over a 22-month period were investigated by a special police task force and the FBI.

During Williams’ nine-week trial, prosecutors contended that the asphyxia deaths of Cater and Payne were part of a pattern of killings that stretched back to July 1979.

Cooper allowed prosecutors to introduce evidence from the deaths of 10 other young Atlanta blacks whose cases were investigated by the special task force. They ranged from 10 to 28 years old. Eight of the 10 victims were under 17.

Williams is the only person who has faced any charges in connection with the 28 deaths. Since his arrest last June 21, no case has been added to the task force list.

Fulton County District Attorney Lewis Slaton, asked after the verdict if the child killing cases are now over, said, “When we had him locked up, I didn’t think there would be any more killings, and there weren’t.”

Credit: Bita Honarvar

Credit: Bita Honarvar

Assistant District Attorney Jack Mallard, who cross-examined Williams last week, said, “The others on the task force list, except the girls, fit the same pattern” as the 12 cases discussed during Williams’ trial. But he added that it would be up to Atlanta Public Safety Commissioner Lee P. Brown to decide the future of the task force investigation.

Asked about Williams’ motives, Mallard said, “I don’t really know. I don’t know if anyone ever will. He had a hatred for lower-class street kids, a warped personality.” Mallard said his cross-examination of Williams, spread over two days, was the longest of his 15-year career as a prosecutor and among the “two or three” toughest.

After the verdict and sentencing, lead defense attorney Alvin Binder said, “It was the fibers, that was all I saw. It sure wasn’t the witnesses.”

Binder said the case will be appealed, but that his involvement with the case would probably end Saturday. Binder also said he would not have conducted the defense any differently if he had it to do over.

Co-counsel Mary Welcome, who was the first attorney that Williams called after he was questioned by the FBI and the task force last June 3, bit her limp and began crying as the verdict was read. Slaton received a congratulatory telephone call from Public Safety Commissioner Brown in his office shortly after the verdict was announced. Brown, who is the man ultimately responsible for the task force, was in the courtroom for Friday's summations, but was out of town Saturday evening.

Asked about the certain defense appeal, Slaton said, “We’re convinced the case will stand appellate review.”

Assistant District Attorney Gordon Miller, who was responsible for presenting the state’s crucial fiber evidence, said the Williams trial is “probably the greatest fiber case ever tried.” He said it could “advance scientific evidence more than any other case in this century.”

“I think we would have had a tough uphill battle without the fiber evidence,” Millers said. “I think it was the key to the whole case.”

The jury of nine women and three men deliberated for more than 11 hours over two days before reaching verdicts in both cases.

The jurors had resumed deliberations Saturday morning after failing to reach a verdict Friday night. They deliberated for just over two hours Friday evening.

Except for a 20-minute lunch break of chili dogs from the Varsity, the panel deliberated almost continuously through Saturday, starting at 9 a.m.

The jury, which included eight blacks and four whites, found Williams guilty of one of the murder charges at about 4:15 p.m. Saturday. Jurors asked Cooper in writing whether they could return one verdict before reaching a decision in the other case.

Cooper called a conference of prosecution and defense attorneys in his chambers. The judge replied in writing that both verdicts had to be announced at the same time, court spokesman Ken Boswell said.

Williams himself was not present during the conference in Coopers’ chambers, Boswell said. After the conference, however, members of the defense team were observed walking toward the room in which Williams was awaiting a verdict.

At 6:30 p.m. the jury foreman, Sandra W. Laney, knocked on Coopers’ door to announce that the jurors had reached a second verdict.

Six minutes later, the jurors left the courtroom, where they had been deliberating because of the volume of physical evidence, so that the press, public, defendant and lawyers could enter to hear the verdict.

The jurors had left several of the prosecution’s fiber charts on prominent display in the courtroom. The charts, which contained photographs of the state’s principal physical evidence under high magnification, dramatically showed links among the 12 cases and between the victims and Williams.

Credit: AJC FILE PHOTO

Credit: AJC FILE PHOTO

At 7:06 p.m., the jurors returned for the last time to the courtroom where they heard 35 days of testimony and one day of closing arguments.

Minutes earlier, the four alternate jurors – who heard the same testimony and arguments but did not participate in reaching the verdicts – entered the courtroom and sat together on a back bench.

After Ms. Laney told Cooper the jury had reached a verdict, he instructed her to hand the original indictment of Williams, with the two verdicts written on it, to District Attorney Slaton.

Slaton’s face betrayed no emotion as he silently read the verdicts he and his staff had worked for over the past nine months.

Then Slaton approached the lectern and read the verdicts aloud.

“We the jury find the defendant guilty on count number one. We the jury find the defendant guilty on count number two,” he said.

Just before the verdict was announced, court spokesman Boswell said Cooper had dismissed the contempt-of-court citations he had filed against defense lawyers Binder and Ms. Welcome, Williams’ parents, and a pathologist from upstate New York who had testified for the defense. All were cited for apparent violations of Cooper’s gag order imposed last August.

After Williams was sentenced, Cooper had the jurors taken to the jury room, where he met with them briefly while lawyers, investigators, reporters and spectators were locked inside the courtroom.

A series of police investigators congratulated Slaton and his assistants during the in-court recess. They included Atlanta Deputy Police Chief Morris Redding, Atlanta police Maj. W.J. Taylor and Georgia Bureau of Investigation Inspector Robbie Hamrick, who together coordinated the task force investigation.

Credit: AJC FILE PHOTO

Credit: AJC FILE PHOTO

At the same time, Williams’ 68-year-old father called the verdict “a railroad job,” and slammed his checked topcoat on the front row of the spectators’ bench where he sat directly behind his son.

On his way out of the courtroom, carefully shepherded out a side door by his attorney and defense aides, Homer Williams paused at the prosecution table to mutter an audible “son of a bitch” at prosecution lawyers.

Slaton nodded acknowledgement and responded tersely, “You’ve had your say.”

The defendant’s mother, Faye, was not present for the verdict. But later Saturday night, in a television interview, Mrs. Williams lashed out at prosecutor Slaton and “his corrupt crew” and characterized Judge Cooper as “their Uncle Tom.”

“The trial proves there is no justice in America,” Mrs. Williams said.

Mrs. Ruby Jones, mother of victim Jimmy Ray Payne, said in an interview it was difficult to express her reaction.

“It’s hard to say (how I feel),” a teary-eyed Mrs. Jones said. “I still, I can’t express my feelings. Up until now it has been hurt and angry … My family feels like it’s falling apart.”

Asked if she believed Williams is guilty, Mr. Jones said, “Well, all the evidence points to him. I feel satisfied that they finally come up with some connection. I feel better about that. But I hope they have the right person.”

The jury in what is believed to be the longest murder trial in Georgia history had to decide whether the 23-year-old defendant was a “mad-dog killer,” as the prosecution contended, or the misunderstood victim of circumstance depicted by the defense.

The jury had much to consider:

- Thirty-five days of testimony from a total of nearly 200 witnesses, including the defendant himself.

- A wealth of complex fiber evidence, including electron microscope photographs, results from fiber color analysis tests, a variety of charts and photographs, plus the fibers themselves mounted on dozens of microscope slides.

- Documents including a financing agreement between the defendant's parents and a firm that installed carpets, a voluminous report on water flow characteristics of the Chattahoochee River, and medical records of one victim's visits to a blood plasma donor center.

In addition, the jurors saw home movies, slide shows, body photographs, aerial photographs, river photographs, and in-person view of the Jackson Parkway bridge, a scale model of the bridge, a live view of the defendant’s dog and two plastic and lead dummies named Ferdinand and Horace. They also considered sound tests on a metal bridge expansion joint, and the impassioned arguments of six attorneys, three representing each side.

It was because of the volume and bulky size of the defense and prosecution exhibits that Judge Cooper decided to have the jurors deliberate in the courtroom itself instead of a jury room.

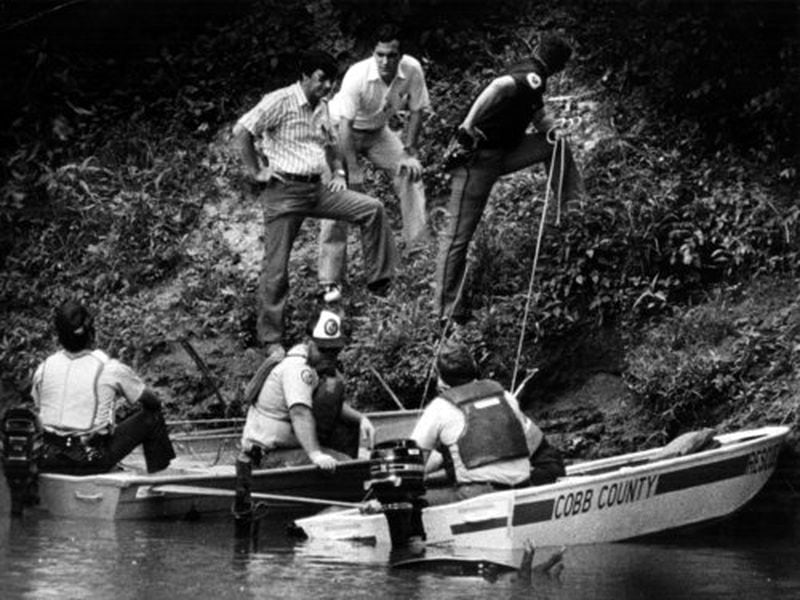

The bodies of the two victims Williams was accused of slaying were found, a month apart, in the same brush-choked portion of the Chattahoochee River. Prosecutors contend the pudgy defendant tossed the bodies off the Jackson Parkway bridge, about a mile upstream from where the bodies were recovered.

Williams came to the attention of police last May 22 when a member of a stakeout team at the bridge heard a loud splash in the river and the defendant’s car was sighted on the bridge.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/ajc/P7DYBH6TO7FEKG4SUXQQKADRXE.jpg)