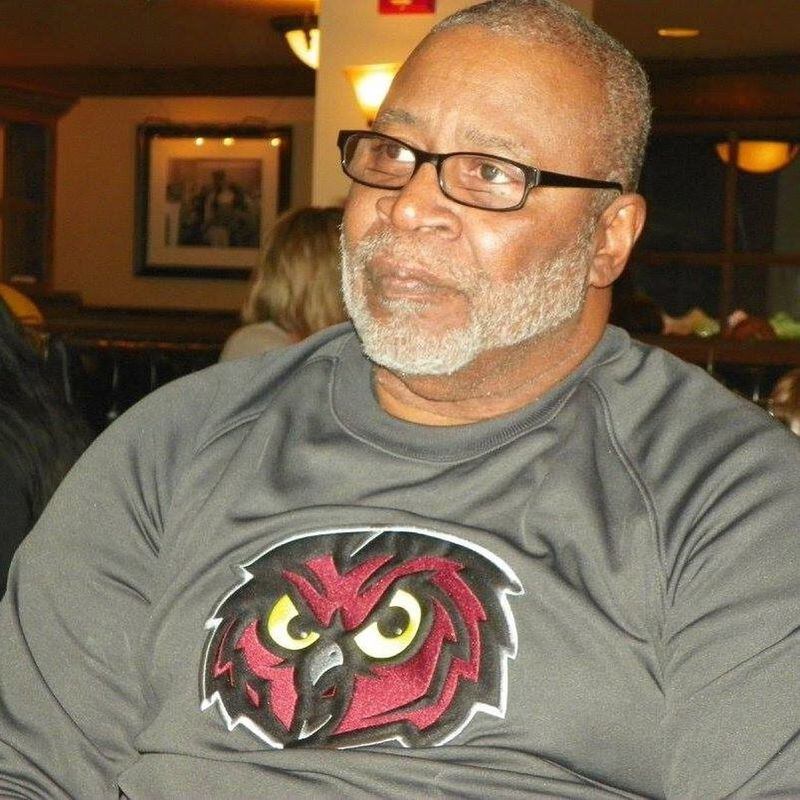

Every day at 5 p.m., no matter what he was doing, Pvt. William Hudson Jr. had to stop and salute the American flag. It was 1968 and Hudson, 20, had just been drafted into the Army.

He was stationed at Fort Jackson, S.C. Next stop: Vietnam.

“That was the tradition. What we had to do,” said Hudson, now 69 and living in Darlington, S.C. “And if we didn’t do that, we would get chewed out.” Nearly 50 years later, he still has great reverence for the flag.

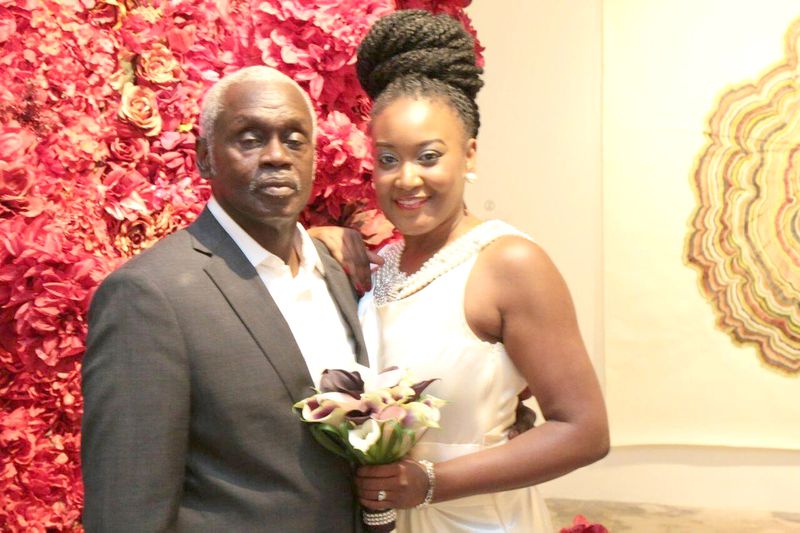

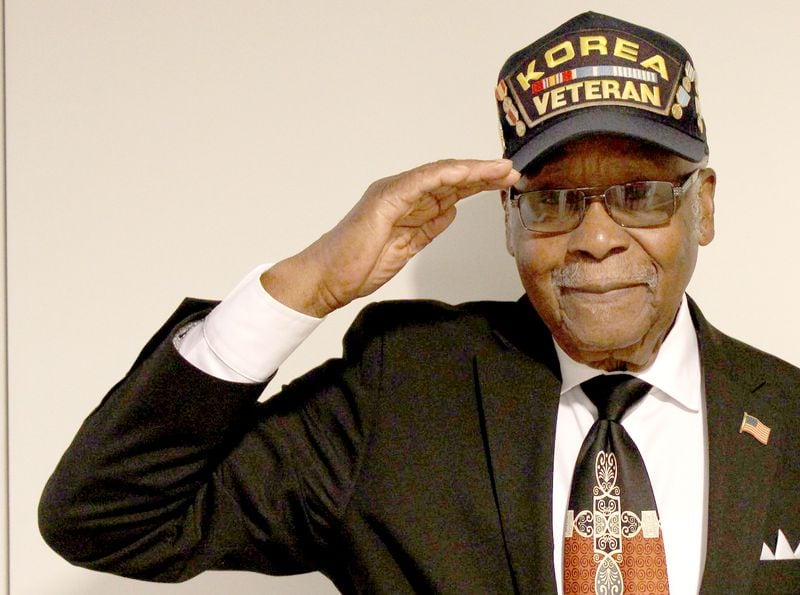

So does James Allen, who served in the Army in Korea. But the flag stirs different emotions in him.

“When I see that flag, there are names that come up in my mind,” Allen said. “Like my buddies Cornelius Charlton and James Breedlove, who didn’t make it back from Korea.”

The flag and what it means have become the focus of a national debate sparked by Colin Kaepernick’s decision last year to take a knee during the national anthem. Kaepernick, the former quarterback of the San Francisco 49er’s, said he did it as a form of protest against the treatment of black people by the police. His critics, including President Donald Trump, say that Kaepernick and the scores of football players who have followed him, are disrespecting the flag, the anthem and the military.

Now, decades after they last saw combat, Allen and Hudson and thousands of other black veterans are thinking about where they fit into the debate.

“They are not disrespecting me and I don’t feel like they are disrespecting the flag,” said Hudson, who served in the U.S. Army from 1968 until 1970. “When I was in Vietnam fighting, I would see people burning the flag back over here. That was disrespectful. But I have never known anybody to get in trouble for burning the flag. If anything, the football players are honoring the flag by showing what unity means.”

Allen, who joined the Army in 1948 and went on to serve as a construction engineer in Korea, doesn’t see it that way. Allen is a retired pest control operator who spent 30 years with the Atlanta Housing Authority, where he earned the nickname “Rat Man.” He said the protests dishonor those who served in uniform — like Charlton and Breedlove.

“There are other ways to protest other than disrespect the flag,” said Allen, 86. “They have the right to protest, but not this way.”

The conflicting opinions of Hudson and Allen reflect two competing narratives in this national debate.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution interviewed more than a dozen black veterans, whose service spanned from World War II to Afghanistan. All but one supported the protests. They all were uneasy about the notion that the protests are in any way a sign of dishonoring them.

“I fought for the right for people to protest,” said Vietnam veteran Dwight Edwards, 71. “We take an oath to defend the Constitution of the United States. The flag comes after that. The flag is a symbol of the greatness of the nation, but the symbol is great because of the Constitution. The flag has no meaning without the Constitution.”

Most veterans emphasized that they were either discriminated against before joining the military or after they got out. The irony, they say, is that they were often thousands of miles away from home fighting for democracy, when there wasn’t equality at home.

“I spent the first nine years of my life in segregated schools. In 1963, there was no Civil Rights Act. No Voting Rights Act,” said Edwards, who joined the Army as an 18-year-old high school dropout in Philadelphia. “So I went to the military to liberate another country, and I didn’t have the right to vote here.”

Edwards was a paratrooper and served in a reconnaissance unit. He said he witnessed whole units get decimated in Vietnam’s Central Highlands.

Which is why Edwards supports the protests. Still active with veterans groups in the Harrisburg, Pa., area, Edwards recently wrote a long missive on Facebook defending Kaepernick, blasting Trump and trying to redirect the conversation to the original purpose of the protests.

“I think it is the duty of every American to stand against injustice and show the world how great we really are through our actions to make the playing field even for everyone,” Edwards wrote. He ended his essay with the blunt: “If, after reading this, you don’t want to be a friend, please delete me.”

Atlanta resident Johnny Miller, 73, was wounded twice in Vietnam, and participated in the Battle of Đắk Tô, a series of tense 1967 battles that saw 361 U.S. servicemen killed. Miller was wounded on Hill 875.

“When I was in Vietnam, Detroit was in flames. Newark was in flames, so I understand protest,” said Miller, who has a Purple Heart. “If I was a player, I would be out there kneeling. This is not about the flag, this is about how police treat black men.”

Kaepernick started his kneeling protests to call attention to the alarming spate of black men dying at the hands of police officers. While a handful of players joined in the protest, Kaepernick’s cause became a red meat topic.

Conservatives called him a traitor. Liberals and African-Americans hailed him as a hero whose stance harkened back to Muhammad Ali.

Last Friday, at a speech to his base in Alabama, President Trump used the term “son of a bitch” to refer to NFL protesters and said they should be fired because they were disrespecting the flag and the military.

In response, nearly the entire NFL joined in some form of protest before Sunday’s and Monday’s games.

“Every soldier that went overseas, went to fight to make sure our families, friends and loved ones back home enjoy their freedoms,” said Adrian Harmon, 31, who served in Afghanistan. “We went to fight for democracy and the right for Colin Kaepernick to stand, sit or protest how he feels like. Kaepernick started all of this because he saw injustice.”

For Allen, who at 86 serves as vice chairman of the Atlanta Housing Authority, said the protests have not cooled his love of football.

“I watched the Falcons pull off a close one Sunday. A win is a win,” Allen said. “But these NFL players don’t know anything about what we went through in the military. When I was discharged from Korea and came into San Francisco, I had tears in my eyes when I saw the flag. You have to be in the military to understand that.”