“Know your history” is undeniably sound advice, and few things bring us closer to knowing history than standing in the places where it happened. Georgia is so full of traces of the past that someone could spend a lifetime visiting the state’s evocative sites and still only scratch the surface of what’s on offer. Here are a few of our favorite historic spots, places that inspire with their beauty while also bringing the state’s complicated and often deeply troubled history to life.

Wormsloe

One of the state’s most fascinating historic spots is also, hands down, one of its most beautiful. The arched entrance to Wormsloe is located off Skidaway Road on the Isle of Hope about a 15-minute drive outside Savannah. Just beyond the gates, the breathtaking 1.5-mile avenue lined with centuries-old oaks dripping with Spanish moss is almost cathedral-like in its architectural grandeur as it leads to the tabby ruins of Wormsloe.

The estate’s owner, Noble Jones, was one of the first European settlers in the colony of Georgia, having arrived with founder James Oglethorpe in 1733. Georgia was unique among British colonies in that it initially banned slavery in its charter, but in 1750 Georgia’s trustees relented to pressure from early colonists like Jones, who could see how profitable the use of African slaves was in nearby South Carolina. Between 1750 and 1775, Georgia’s population of enslaved people grew from about 500 to 18,000 as one of the great tragedies of history unfolded with plantations like Wormsloe right at the epicenter.

Most visitors drive through the impressive row of oak trees (some arrive to do just that and then turn around to leave), but it’s worth getting out of your car to visit the museum, to walk to the tabby ruins, to see the reconstructed colonial life area and especially to stroll along the oak alley itself, now like a quiet, haunting monument to one of the most significant turning points in Georgia’s history.

Wormsloe State Historic Site, 7601 Skidaway Road, Savannah. 912-353-3023, www.gastateparks.org/Wormsloe.

Etowah Indian Mounds

People lived in Georgia long before European settlers like Oglethorpe and Jones arrived, of course, and one of the places this is most evident is the Etowah Indian Mounds Historic Site near Cartersville, about a 45-minute drive from Atlanta. Studies show that the site was built and occupied in phases beginning around A.D. 1000.

By climbing the stairs to the top of the largest mound — it’s taller than a six-story building and believed to have been used as a platform for the home of the priest-chief — a visitor can survey the expansive 54-acre archaeological site. With a wide view taking in the other mounds and the sprawling, raised central plaza, a visitor can begin to picture the thriving, moated village that once occupied the spot.

Enormous “borrow pits” nearby show where the earth was dug out to create the mounds, and the informative museum adjacent to the site has an interesting collection of artifacts, including a fascinating pair of marble effigies, one man and one woman weighing about 125 pounds each, found at Mound C and believed to have been created as early as the 13th century.

Etowah Indian Mounds Historic Site, 813 Indian Mounds Road S.W., Cartersville. 770-387-3747, www.gastateparks.org/EtowahIndianMounds.

New Echota

About 30 miles north of the Etowah Mounds is the site of a much later, and very different, Native American town. New Echota was officially designated as the capital of the Cherokee Nation in 1825. During its short life, the town hosted lively Cherokee Council meetings with hundreds of visitors and representatives arriving from across the Cherokee Nation, its print shop published the first Indian-language newspaper using the new syllabary famously created by Sequoyah, and its court tried a case that went to the Supreme Court of the United States.

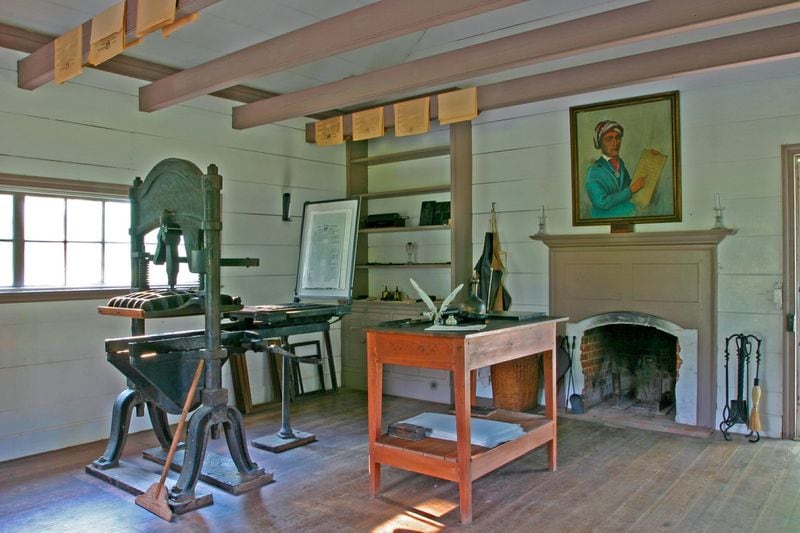

The story of Indian removal, which culminated in the Trail of Tears, is told in the museum’s interpretive exhibition, and the heart-rending tragedy and sheer injustice can come to vivid life through reading some of the original newspaper accounts and editorials from the Cherokee Phoenix. But history seems most present when wandering the site of the town itself. Visitors can walk the former streets to see 12 original and reconstructed buildings, including log cabin homes, the courthouse, the newspaper print shop, the home of missionary Samuel Worcester and an 1805 tavern, all of which create an immediate and moving sense of what life was like in the former town.

New Echota State Historic Site, 1211 Chatsworth Highway N.E., Calhoun. 706-624-1321, www.gastateparks.org/NewEchota.

Chief Vann House

Few Georgia sites give a more complex sense of a person than the Chief Vann House, about 20 miles from New Echota on the outskirts of Chatsworth in Northwest Georgia. James Vann was one of the wealthiest businessmen in the Cherokee Nation, and he created the impressive brick home as a showplace after he became one of the Cherokees’ several chiefs.

Vann was a slave owner, and though the exterior of his welcoming, elegant home gives little indication, he was known to be brutal, cruel and abusive, even of questionable sanity. A creepy basement chamber is said to have been used for torturing rebellious slaves, and it still induces shudders. Vann made many enemies during his lifetime, and he was eventually murdered outside a tavern in 1809.

During and after Indian removal, the house became the focal point of contested claims of ownership, and visitors can see the burn marks on the cantilevered staircase from a smoldering log that was thrown there to terrify the house’s then-occupants.

Chief Vann House Historic Site, 82 Ga. Highway 225 N., Chatsworth. 706-695-2598, www.gastateparks.org/ChiefVannHouse.

Andersonville

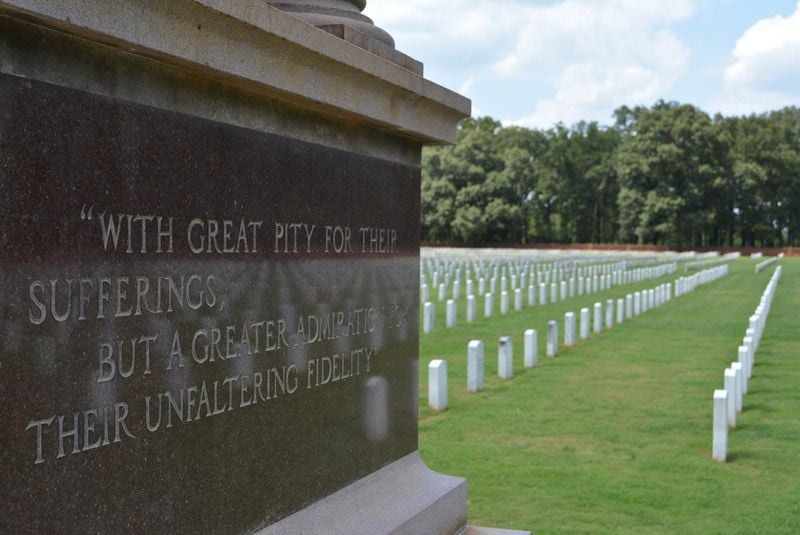

Andersonville is only about an hour’s drive southwest of Macon, but it truly feels like it’s in the middle of nowhere. There’s a reason for that. The spot was originally chosen to hold captured Union soldiers during the Civil War precisely because of its isolation. Through a combination of cruelty, poor planning and the deprivations of war, things went terribly wrong at Andersonville, and the prison became what survivors later described as hell on earth, overcrowded to four times its capacity and subject to starvation, lack of fresh water, disease, parasites and violent infighting. Almost 13,000 of the 45,000 men imprisoned there died.

The interpretive center gives information about the horrors that unfolded at Andersonville, and it also houses a fascinating exhibition dedicated to American prisoners of war from throughout the nation’s history. Walking the site’s perimeter, where there are re-creations of sections of the stockade walls and gates, gives the best sense of the scope of the former prison. You can still dip your fingers into the spring of lifesaving fresh water that appeared one night after a lightning strike which the prisoners believed was a miracle.

Finish your visit by honoring the dead at the Andersonville Memorial Cemetery, where after the war, the “Angel of the Battlefield,” nurse Clara Barton, who later went on to found the American Red Cross, helped identify and mark the graves of those who had died at Andersonville.

Camp Sumter military prison, Andersonville National Cemetery and National Prisoner of War Museum, 496 Cemetery Road, Andersonville. 229-924-0343, www.nps.gov/ande/index.htm.

RECOMMENDED VIDEO: Georgia hidden treasures: National Parks

About the Author