Every museum exhibition is a matter of choices. But "Making Africa: A Continent of Contemporary Design" at the High Museum of Art feels like an especially tall order.

Its lofty goal is to convey the richness of African design and creativity in a mere 135 objects. As a result, "Making Africa" feels less like a conventional museum exhibition and more like a proposition to occupy, momentarily, a head space. It asks you to get inside a place through a collection of its things.

Organized by Germany’s Vitra Design Museum and Spain’s Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, “Making Africa” makes an ardent, convincing case for the many ways design shapes consciousness. Contained in the title is the idea of Africa as an identity in formation, and how the work of designers, artists, architects and filmmakers can define what Africa can be.

Objects on display come from a head-swimming variety of disciplines; film, web and video game design, activism, fashion, street photography and architecture. Many of those things are displayed in a manner that can suggest a highly conceptual shopping experience a la an Apple or Nike store, set apart on white plinths and offered up with some very appealing staging.

In what may be the most compelling phase of the show, "I and We," interconnections between identity and society are examined in a variety of quotidian objects. They include a website, HarassMap, in which ordinary citizens take an active role in countering sexual harassment on Egypt's streets by providing a kind of Waze crowd-sourced chart of its occurrence and offering advocacy for its victims.

Sharing that “I and We” exhibition space are thrilling paeans to youth culture from early practitioners like Malick Sidibe, whose romantic, joyful 1963 black-and-white photo of a stylish young Malian couple dancing flows into modern examples of street fashion like South Africans Malibongwe Tyilo’s and Jody Brand’s style blogs. Fashion crops up at numerous turns in “Making Africa” as a thrilling site of self-invention, but also as a source of social commentary. Later in the show’s “Origin and Future” section focused on a mashup of Africa’s history with visions for the future, Dutch waxcloth fabric is both embraced and rejected for its colonialist associations. What emerges in “Making Africa” is a feeling of a world in formation where the highly coded nature of traditional African dress has collided with a modern world where new codes and meanings are conveyed.

The continent as it is depicted in “Making Africa” is otherworldly, a hybrid of dystopia and utopia where gritty social realities of poverty, war and gender bias clash with a vision of the future nothing short of visionary. The mood is set in the exhibition entrance, a wall of talking heads featuring various curators, consultants and thinkers testifying to the complex and potentially foolhardy proposition of defining Africa as any one thing.

A metaphor for another way of seeing that “Making Africa” demands, the first artworks on view are Kenyan artist Cyrus Kabiru’s steampunk-meets-upcycled “C-Stunners” eyeglasses fashioned from materials like tin cans, spoons and wire. That idea of beauty forged from discarded items continues throughout the exhibition in sculptures made from used tires and a throne crafted from spent grenades, rocket launchers and pistols. One of the most moving and unexpected inclusions in the show is a pair of flip-flops made by an ordinary African from smashed plastic soda bottles and wire laces thoughtfully appropriated by artist Kader Attia to convey a depth of creativity and inventiveness in the face of poverty.

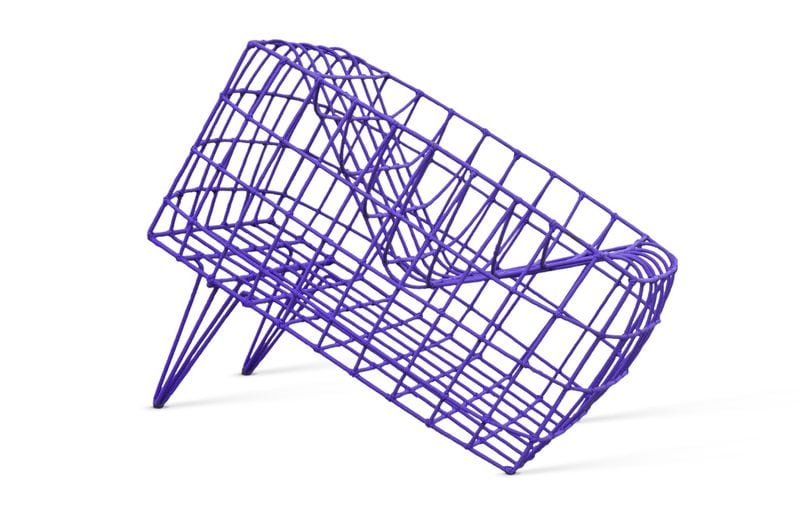

Decorative objects often take on surprising, subversive meaning, as in “Sun City,” a drink cabinet by design firm Dokter and Misses in which the kind of burglar bars used in South African homes to protect home and possessions become a provocative, politicized decorative flourish in a home bar.

On view at various turns in “Making Africa” is what advising curator (working with curator Amelie Klein) Okwui Enwezor calls “the renegade practice of making.” In a First World of both wealth and entitlement, the avidity with which both artists and ordinary people hustle and hype in this original gig economy is a wake-up call. “Making Africa” is nothing short of awe-inspiring for the way its citizens are shaping their reality with the means at their disposal.

ART REVIEW

“Making Africa: A Continent of Contemporary Design”

Through Jan. 7. 10 a.m.-5 p.m. Tuesdays-Thursdays and Saturdays; 10 a.m.-9 p.m. Fridays; noon-5 p.m. Sundays. $14.50, ages 6 and above; free for children 5 and younger and members. High Museum of Art, 1280 Peachtree St. NE, Atlanta. 404-733-4444, www.high.org.

Bottom line: A transportive collection of design, ideas and objects that advocate for an Africa blending a difficult history and a visionary future.