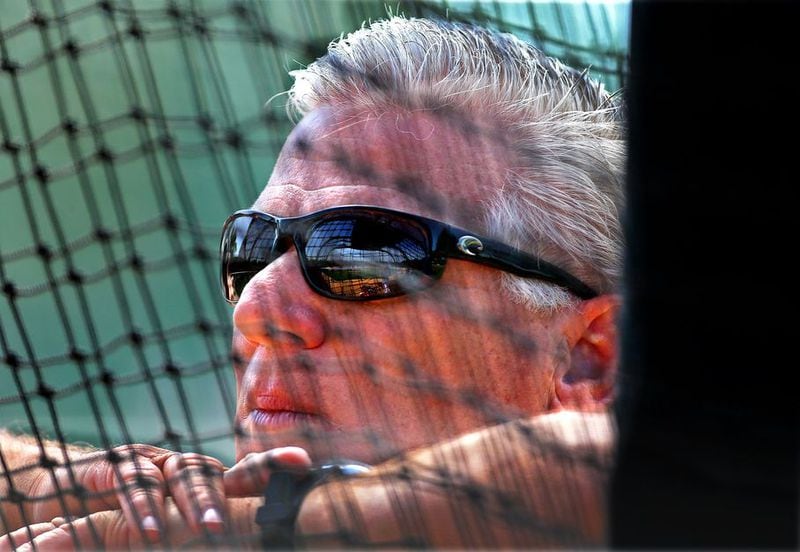

Credit: Mark Bradley

Credit: Mark Bradley

It wasn't so long ago -- on Monday, July 7, to be precise -- that these fingers offered up a few hundred words in defense of Frank Wren . My reasoning, such as it was: Since 2010, the Atlanta Braves had won more regular-season games than any team in baseball, and I believed that Wren's offseason push to re-up four key pieces of the team's young core would secure the future of the franchise. (I should also note that, at that moment, the Braves led the National League East.)

Today the Braves fired Frank Wren, and this former defender cannot rise to object.

Back in July, I couldn't have imagined that a team so talented could go a full season without hitting a lick. Back in July, I wouldn't have dreamed that the long-term re-ups of Freddie Freeman and Andrelton Simmons could ever be considered short-sighted, but here it is Sept. 22 and Freeman has only seven more home runs than B.J. Upton and Simmons' on-base percentage is .004 better than Bossman Jr.'s, and when you're being compared to the player who essentially brought down this general manager ... well, you haven't exactly branded yourself a windfall, either.

I credit Wren for inheriting (in October 2007) a franchise coming off two consecutive non-playoff seasons, the latter of which featured the decimate-the-farm-system trade for Mark Teixeira, and rebuilding it by 2010. The Braves won 91 games that season. They won 89 in 2011, the year of the Epic Collapse. Then 94. Then 96. They made the playoffs three times in four seasons. They won the National League East for the first time since 2005. But B.J. Upton changed everything.

Don't make the mistake of lumping Dan Uggla with Bossman Jr. Uggla had stamped himself a consistent run-producer over five seasons as a Marlin. Trading for him and then re-signing him for $62 million over five years should have worked; it just didn't. A proven hitter simply stopped hitting, and we'll probably never know why. (Or even if there is a "why.")

Signing B.J. Upton for $75 million was a huge bet on potential over production. The Braves had scouted him heavily -- Jeff Wren, Frank's brother, and the late Jim Fregosi were the point men -- and believed him to be worth the massive contract. (That contract, it must be said, was in keeping with what sabermetric types believed Upton would indeed draw in free agency; Keith Law of ESPN ranked him the No. 1 position player available that winter.) There was always risk involved, but nobody would have dreamed that such a talent would, in new surroundings playing alongside his brother, become one of the five worst players in the major leagues.

And suddenly it wasn't one big Wren acquisition that had gone bust. It was two everyday players, two to put on the same shelf as the pitchers Derek Lowe and Kenshin Kawakami. (Though I'd argue that Lowe wasn't a total flop; the Braves wouldn't have made the playoffs in 2010 without him.) When finally the Braves paid Uggla to go away, the clock started ticking on B.J. Upton. When this batting order failed to coalesce despite the lineup-card gyrations performed by Fredi Gonzalez, the attention turned to lineup composition -- lots of big swingers who'd become bigger missers, meaning lots of rally-killers, meaning no rallies.

On paper, this lineup looked potent enough. On the ballfield, it looked awful. You wouldn't have imagined a team with Freeman, Jason Heyward, Evan Gattis and Justin Upton could be second-worst (to San Diego) in runs, but it has been virtually all season and is today. Not since 1989 has there been a Braves' offense so puny, and that was when Russ Nixon was managing kids and retreads.

The redone contracts that seemed sagacious in the spring were rendered suspect, at least in the short term. Is Freeman worth $135 million over eight years? (In other words, is he a Franchise Player?) Is Simmons worth $58 million over seven? (He might be worth it on defense alone, but his hitting regressed in 2014.) There's no quibbling with the re-ups of Julio Teheran and Craig Kimbrel, but Freeman and Simmons haven't had the seasons anyone expected.

That's the peril of being a GM: You rise or fall with your signings. You can oversee a good farm system, as Wren did, but it's the big-money moves that are the makers/breakers. Wren was deft at smaller stuff -- think Aaron Harang, Eric O'Flaherty, Jair Jurrjens, Jordan Walden; think also the reclamation projects Troy Glaus and Ben Sheets, who had one good month each -- but he whiffed on Uggla and whiffed on Bossman Jr. and, largely because of those whiffs, built a lineup that will need rebuilding.

If Wren hadn't been quite so abrupt -- he's always a man in a hurry -- in his personal dealings, he might have engendered more in-house good will. But Wren was something of a micro-manager, which the revered John Schuerholz hadn't been. Any move of Wren's that didn't work would be received with glee in some sectors of the organization, as if the know-it-all had just been handed another cup of comeuppance. It would be wrong to say that Wren was widely disliked; it would not be wrong to say that he'd made few allies.

His demeanor didn't matter so long as the Braves were winning, and it's not fair to suggest that his demeanor got him fired. B.J. Upton got him fired. Signing B.J. Upton was the biggest move of Wren's seven years as GM, and it wrecked everything. In his first year on the job, the biggest free-agent signee in team history was reduced to pinch-hitting in the NLDS against the Dodgers. (He struck out three times.)

Upton was slightly better this year only because he couldn't have been worse, and by then Wren's legacy was rewritten. No longer the GM who'd led the Braves back to prominence, he was the guy who'd had to buy out Uggla. And now some other man will get to buy out Bossman.

About the Author