An interesting take last week from Arizona Cardinals coach Bruce Arians on the recent Department of Defense policy shift back toward requiring service-academy players to fulfill a minimum two-year military commitment before trying to make a pro roster.

“I think it’s dumb,” Arians said. We promised interesting, not erudite.

All the same, I think I’ll stand on the other side of the room from that argument.

Having long ago given up on the ideal that a college’s primary mission is to educate rather than entertain during a handful of fall Saturdays, can we at least hold onto the rather important work of the military academies? It would be nice if those who graduated from Army, Navy and Air Force spent some meaningful time in a uniform that didn’t have a number on it.

I think that’s rather smart.

Especially given the hundreds of thousands of dollars invested in educating each recruit.

Hard to believe but, yes, there are some ethics that shouldn’t be compromised by football. That may be heresy in this part of the country, but I'll take my chances.

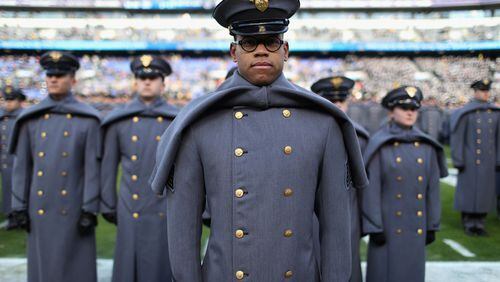

The policy of what to do with promising service-academy athletes is a regularly shifting one. What got Arians upset was the DOD tilt last month away from allowing football players to sign with teams upon graduation and fulfill their military commitment as a reservist and back toward immediate assignment, just like all the other cadets who occupied the stands at the Army-Navy game.

Thus it was that Air Force’s Samuel Byers was at the Falcons' rookie minicamp last weekend hoping to make some sort of long-lasting impression before he was to report to Hill Air Force Base in Utah for his first assignment as an acquisitions officer, according to the Colorado Springs Gazette.

He was among a handful of players in that position, seven at last count. Byers’ situation was further complicated by a position change - a defensive lineman in college auditioning as an O-lineman.

All those obstacles can be overcome – there is an example on the Falcons' own roster. Ben Garland played defensive line at Air Force and is a backup Falcons interior offensive lineman. He survived a two-year military hitch before getting back in the football pipeline (although he had to give up dreams of becoming a pilot to jump back into football).

The point is that when a young person accepts a position at one of these academies, he or she it knows full well that it comes with obligations and higher callings.

For those of certain abilities, none of those higher callings include making an NFL practice squad.

You respect the differences between the service-academy player and, say, the SEC one. You salute them. You celebrate them. Because they are too important, you don't blur them.